No One Will Remember Your Name: An Essay on Immortality

by Thomas Wolanski

Thomas Wolanski explores the difference between merely existing and truly living, urging us to seek glory and immortality through exceptional deeds.

Energy. Vitality. Vigor. We use these and perhaps a dozen other adjectives in the English language to describe positive and desirable states of being. Phrases are thrown about in pop culture which refer to the quality or type of life we wish to lead, phrases like “I’m here for a good time, not a long time,” or “better to live a day as a king than a year as a peasant,” and even the succinct “YOLO.” If one traces the roots of these platitudes far enough, they hearken to a mindset held by our ancestors that encouraged the development of a reputation that would survive its holder beyond the grave.

A distinction exists between life and living. Life, the state of mere existence, is a condition partaken in by all living human beings through no other means than that of having been born and not yet having died. Life requires little exertion and, when lived at its most basic, will demand nothing more than the fulfillment of basic biological imperatives. When one reads, a concept often expressed in literature is that of mere life being unfulfilling and unsatisfactory to higher types of humanity. The life of the masses, the life of the mediocre, the life of the quantity, these are representative of the lowest forms of meagerness — nothing more. Marked only by its duration or span, this life leaves no mark on the world past its cessation.

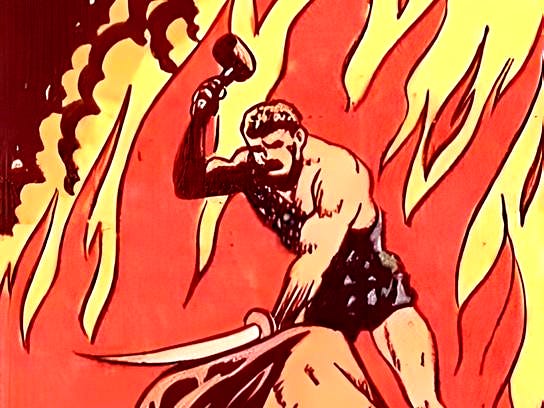

In contrast to life, we can partake in living. Living is an active rather than passive form of existence. One can live and then cease to live, remaining simply alive. Living requires periodic and intentional decisions to maintain its state. Living is also not tied to a biological state of life. One can live even after the earthly heart has stopped beating. Immortality is achieved thus, through a life that ensures the memory of one’s existence after one’s death1 rather than simply achieving a state of infinite biological life (the modern and mundane idea of immortality). Here we may draw a line between the two forms of immortality: that of biology and that of glory. As men, we must concern ourselves with the second type.

The ancients understood glory in a way we never shall. In the 2004 movie Troy, Achilles (played by Brad Pitt) is told by a messenger boy that the Thessalonian warrior he is about to fight is enormous and that the boy would not want to fight him. Achilles responds tersely by saying, “That is why no one will remember your name.” A modern example, to be sure, but a poignant one nonetheless. Glory and immortality are achieved through living. Truly living. A man concerned with the mere necessities and niceties of life, or, worse, with the simple preservation of life, cannot experience this. Imagine making it to the end of your life having not one achievement of significant merit to outlast your final breath. I imagine that most readers of this essay would feel revulsion or distaste for such a life, and yet it is just this form of base existence that the vast majority of mankind partake of.

No man is remembered without good reason, and no man has good reason for being remembered without being exceptional. It may be argued that there are plenty who are remembered for their more negative aspects, but I would say that these men are not truly immortalized but merely evoked when mankind needs examples of what not to do. True glory is achieved only through attainment. A man cannot simply wish for it.

To achieve immortality, a philosophy of life affirmation is necessary. The man who thirsts and hungers for life2 is the man who understands this. Life has greater value when it is traversed with a view to actually living. Even the man who, for example, achieves immortality through an action of self-sacrifice and attainment of glory through his death understands this because, through achieving a great deed as he dies, he affirms that living to do his great deed was worthwhile — and that his deed is perhaps even more worthwhile than the continuation of his life.

A quote from Ivan Karamazov in The Brothers Karamazov (1880) gives us a picture of what thirst for life looks like. Ivan tells his brother, “You wouldn’t believe, Alexey, how I want to live now, what a thirst for existence and consciousness has sprung up within me within these peeling walls… [a]nd what is suffering? I’m not afraid of it, even if it were beyond reckoning … and I seem to have such strength in me now, that I think I could stand anything, any suffering, only to be able to say and to repeat to myself at every moment ‘I exist.’ In thousands of agonies — I exist.” This quote and the book it comes from are examples of existentialist philosophy, which can be construed as contrary to my message of living with the intent to achieve glory.3 But I would argue that one should rather interpret any thirst for life as having been first induced by the possibilities of what that life could hold.

I do not for one second believe that any man reading this is deluded enough to imagine that achievement comes easy. Even in our mundane and mediocrity-aspiring culture today, we are often reminded of the difficulty of greatness. I also know that most men instinctively understand what they must do to better themselves so as to be optimally positioned to seize greatness when it comes within reach. Fill your life with those things and influences that you already know are best.

But what can a man do? After all, not every man is born to be a Caesar or Bonaparte. The objectivity inherent in great deeds is framed by the living of subjectively different lives. Man achieves by whatever means he is best suited for, and whatever means he is most driven to. War, art, literature, politics, architecture, music, all these and more are available means. Above all, improving the mind and the physical body are prerequisites to any other form of greatness.

So let us live our lives as Western men with glory and immortality as our end. We understand that truly living is the only path to a fulfilling life, and that a passionate existence with all it may entail is vital. As William Wallace said, “Not all who die truly live.”

Another form of immortality is that of achieving immortalization through having progeny (referenced, for example, in Plato’s Symposium). While I encourage and fully support this concept, it is not the topic of this essay.

Life is to be understood here as truly living, as previously discussed.

Existentialism is a philosophy which, among other things, proclaims the virtue of all life qua life. See the famous quote by Camus regarding philosophy and suicide.

Sounds good just like gazillion pages of self-help written during last several decades. The problem is that one needs both noble blood and be initiated in order to "truly live", or to at least be subordinated to these kind of men. These men do not exist, or are at least not visible, for a long time. Great mystery is how are they going to appear again.

Celtic pagans believed they would be reborn into their family lines, therefore death had no hold on them, and by assisting the family one assists future incarnations by proxy. Guido von List asserts the same for Germanics. Reincarnation along genetic lines is, to me, the real form of immortality. Genetic memory preserves elements of the spirit.

Genes remember too.