Decadent Chronicles 3: Unemployed Hercules

by Christian Chensvold

Christian Chensvold, invoking Baudelaire’s mystical dandy and Evola’s aristocrat of the soul, presents dandyism as a spiritual discipline for the superior man to assert regal bearing amid the disintegration of Tradition in a world of mediocrity.

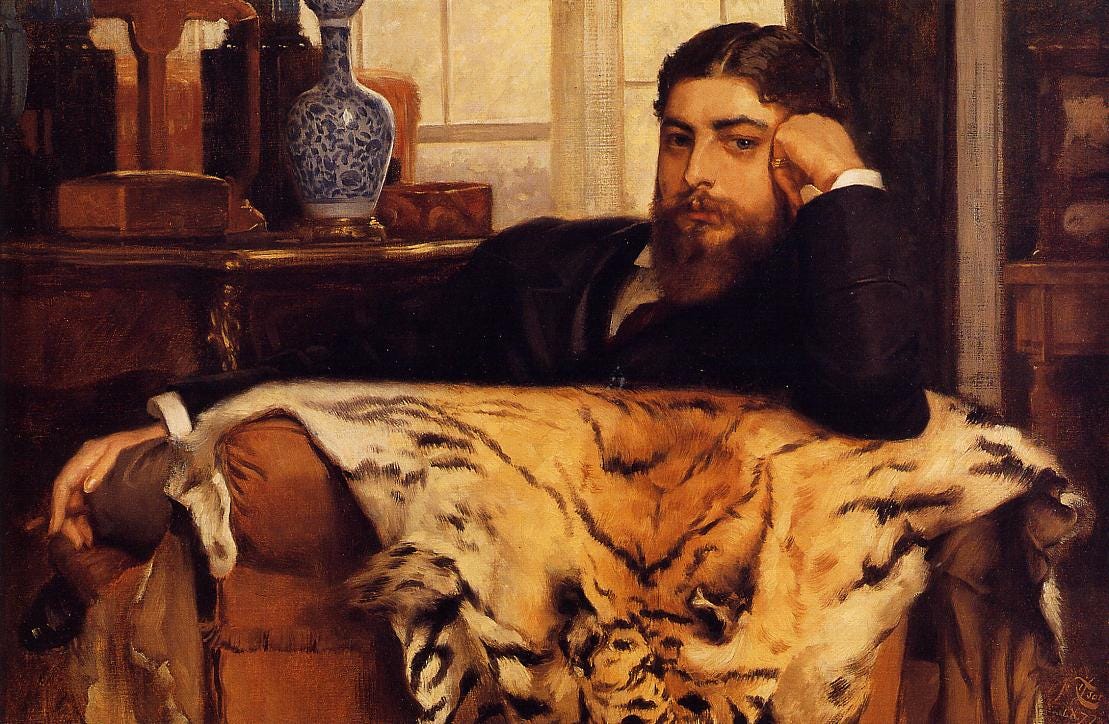

What does the superior man — Evola’s aristocrat of the soul, or man of Tradition — do in an age of mediocrity and machines, egalitarianism and consumerism?

For Charles Baudelaire, poet and critic, father of Modernism, and guiding spirit of the Decadent Movement (1880-1914), the superior man creates a code of conduct he secretly imposes on himself in an effort to rise above his base nature. He undertakes risky sporting feats, forces himself to be elegant at all times, and cultivates stoic impassivity, embodying Machiavelli’s dictum, “The world belongs to the cool of head.”

The word Baudelaire chose for this cult of superiority in the wake of industrialization and democracy and their terrible leveling influence was dandyism. The dandy was an English figure of the Regency period exemplified by George Bryan “Beau” Brummell, but the Frenchman raised it to archetypal stature in his short but poignant 1866 essay “The Dandy.” Faced with the rapid unfolding of the modern world, the figure of the dandy, the self-made aristocrat, becomes an “unemployed Hercules,” exhibiting “the last stroke of heroism in times of decadence.”

Baudelaire’s dandy is a last-ditch offshoot of medieval chivalry, who demonstrates his superiority not on the battlefield nor in courtly life, but in the modern world of boulevards and cafes, shops and theaters. Quixotically noble, the dandy was a man of Herculean spirit with nothing to do, surrounded by mediocrity and materialism yet determined to rise above it, playing games with himself to test his nerve and verve.

Just as religions have two sides — a metaphysical teaching for the regal and sacerdotal guardians, and a simplified version for the masses — Baudelaire’s essay displays an exoteric side ostensibly concerned with the charms of high life, and an inner esoteric teaching capable of being deciphered by spirit-seeking initiates.

Distilling the text in an alchemical cauldron to purify its essence and extract its golden wisdom, we end up with something like this:

Dandyism is a kind of aristocracy that is difficult to break down because it is founded on indestructible divine gifts. It is a doctrine, a monastic rule, a rigorous code to which certain disenchanted outsiders are strictly bound.

Dandyism is a strange form of spirituality, almost a religion, fueled by a burning desire to create oneself, and stemming from an aristocratic superiority of mind.

Fueled by a latent fire, the dandy’s native energy is the source of his haughty, patrician attitude, aggressive even in its coldness.

Dandyism strengthens the will and schools the soul, bestowing a calmness revealing strength through risky sporting feats and a flawless dress of elegance and distinction.

The dandy is a champion of pride who destroys triviality through opposition and revolt.

Dandyism is a setting sun, magnificent and full of melancholy. It is the last flicker of heroism in decadent ages, when democracy and egalitarianism are not yet all-powerful.

Baudelaire’s illuminating language thus hints at a modern “mystery” of dandyism, connecting it to earlier spiritual paths rendered inaccessible in the age of decadence. Dandyism demands the adept synthesize all aspects of himself, from masculine audacity to feminine grace, and bring them under the dominion of a single authority, the will. It bestows supernatural poise, an attribute of a regal spiritual virility necessary for the superior being living in the age of mass recollectivization. Winding back through time towards the origins, this path intersects with the Ars Regia or Royal Art, and from there to the Primordial Tradition, to mankind’s original archetypal unity and divine nobility, a state radiant of an otherworldly dignity no devotional piety can bestow.

Consider this passage from Julius Evola’s essay “Aristocracy and the Initiatic Ideal,” from his early work with the UR Group in the 1920s, or 60 years after Baudelaire’s essay:

The aristocratic way of being is typified by a superiority that is virile, free, and personalized. It corresponds to the demand — which had typical expressions in the classical world — that what is lived internally as spirituality should manifest outwardly in an equilibrium of body, soul, and will; in a tradition of honor, high bearing, and severity in attitude, even in the details of dress; in a general style of thinking, feeling, and reacting. Even though from the outside it may seem like mere formality and stereotypical rules (into which nobility may often have fallen), that style can be traced to its original value as the instrument of an inner discipline: to what we might call a ritual value.

While some knights were of noble birth, medieval chivalry opened the possibility of acquired nobility. In the modern world, when Traditional paths of ascension are closed, Baudelaire offered dandyism as a newly forged path along an ancient journey, in which the hero achieved noble stature in a spiritual realm outside of space and time. Baudelaire’s dandy essay, along with all his writings, had a tremendous influence on the Decadent Movement a generation later, when democracy and materialism began to rapidly accelerate, and a growing number of men felt called to forge a path that would bestow upon their souls the consciousness of being self-made aristocrats.

~

Christian Chensvold is a college fencing champion, third-generation astrologer, founder of Dandyism.net (2004), and author of The Philosophy of Style (2023) and Dark Stars: Heroic Spirituality in the Age of Decadence (2024). He is currently writing a work of 21st-century mythology, a Hyperborean Gothic fantasy that seeks to inspire Europa at the time of its greatest crisis.