Decadent Chronicles 2: The Serpent

by Christian Chensvold

Christian Chensvold unveils how the Decadent Movement (1880-1914), infused with esoteric symbolism and the eternal image of the serpent, became a visionary struggle between Western man’s heroic will to order and the chaotic forces of civilizational decline that still menace us today.

Also read part one.

The Decadent Movement in art and literature (1880-1914) wrestled with the problem of civilizational decline like a Hyperborean Apollo grappling with the serpent Python.

Throughout the world of Tradition, the serpent was used as a symbol of the primordial energy driving the universe. It takes but a rudimentary study of esotericism to understand why: a snake moves left and right at the same time. The primordial energy it symbolizes is therefore neutral and can be used for good or evil depending on the intention of the person, government, or metaphysical principle — such as evil and destruction — operating it. This serpentine cosmic force winds around the caduceus of Hermes as two snakes, representing the principle of dualities such as light and dark, spirit and matter, civilizational ascension and civilizational decline. The serpent has also been depicted as the ouroboros, or snake devouring its own tail, expressing the metaphysical concept of eternity, with beginning and ending reconciled and returned to the same place.

In the world of Tradition, the serpent is also referred to as a dragon, which in the 1981 film Excalibur Merlin reveals through the magic of his dual-snaked staff, causing Morgane Le Fay to scream in horror when she beholds the promordial energy, in which anything is possible and everything meets its opposite. The illumined spirit must take command of this primordial energy by symbolically placing one’s foot upon its head, explains Eliphas Levi, the Catholic occultist who exerted a tremendous influence on the Decadent Movement, which overlaps with the French Occult Revival at the close of the 19th century. As Levi repeatedly expounds, the serpent, or Astral Light as he liked to call it, is saturated with archetypal images, and the metaphysical explorer who discovers this dimension of consciousness either emerges victorious and enlightened or else goes mad.

As Western Civilization reached its apex, the image of the serpent appeared in the mind’s eye of artists and writers, who unconsciously “downloaded” from the Astral Light visions of the perennial struggle between the ordered cosmos and primordial chaos. This struggle to give form to undifferentiated energy is the story of the Book of Genesis and is examined in the work of figures such as Julius Evola and Mircea Eliade as the very starting point of civilization. Decadent Chronicles here sets the stage for our future examinations of the artistic output of the period with three depictions of the mythological serpent, expressing the growing unease of the European imagination as it reached its peak and stared down the other side at the slippery slope of decline.

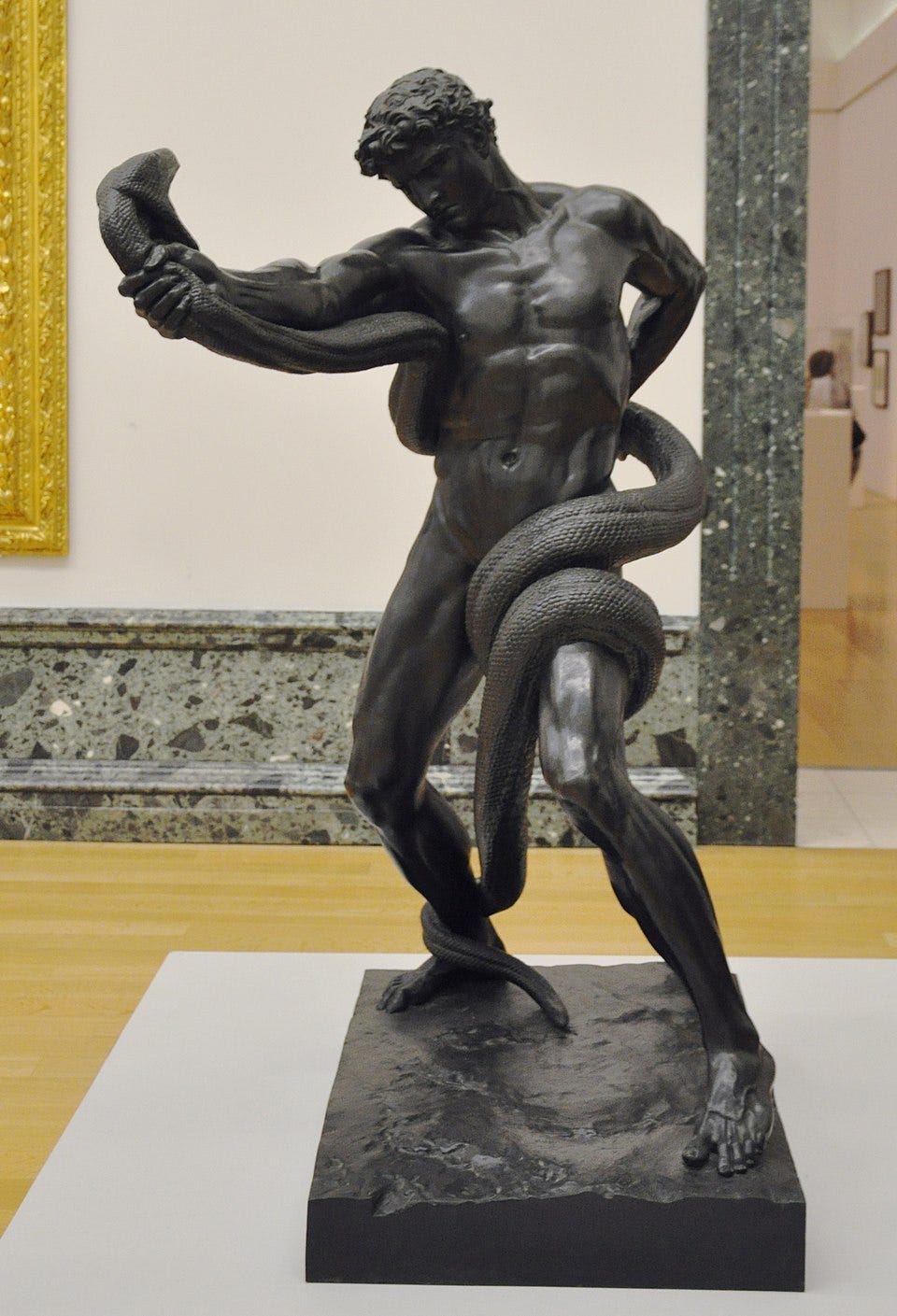

The first is executed in an academic and neoclassic style: Lord Leighton’s An Athlete Wrestling with a Python from 1877, which in our context we read as an allegory of the coming crisis of Western man as he loses control of the world he created. What he has unleashed — the world of mass recollectivization and chaos — is better represented, however, not as a single serpent but rather the Hydra, whose seven heads stand for all the “isms” all too familiar to the reader in 2025 when every bourgeois institution — liberal democracy, capitalism, media, education, judicial system, culture — has been hijacked by the force of subversion.

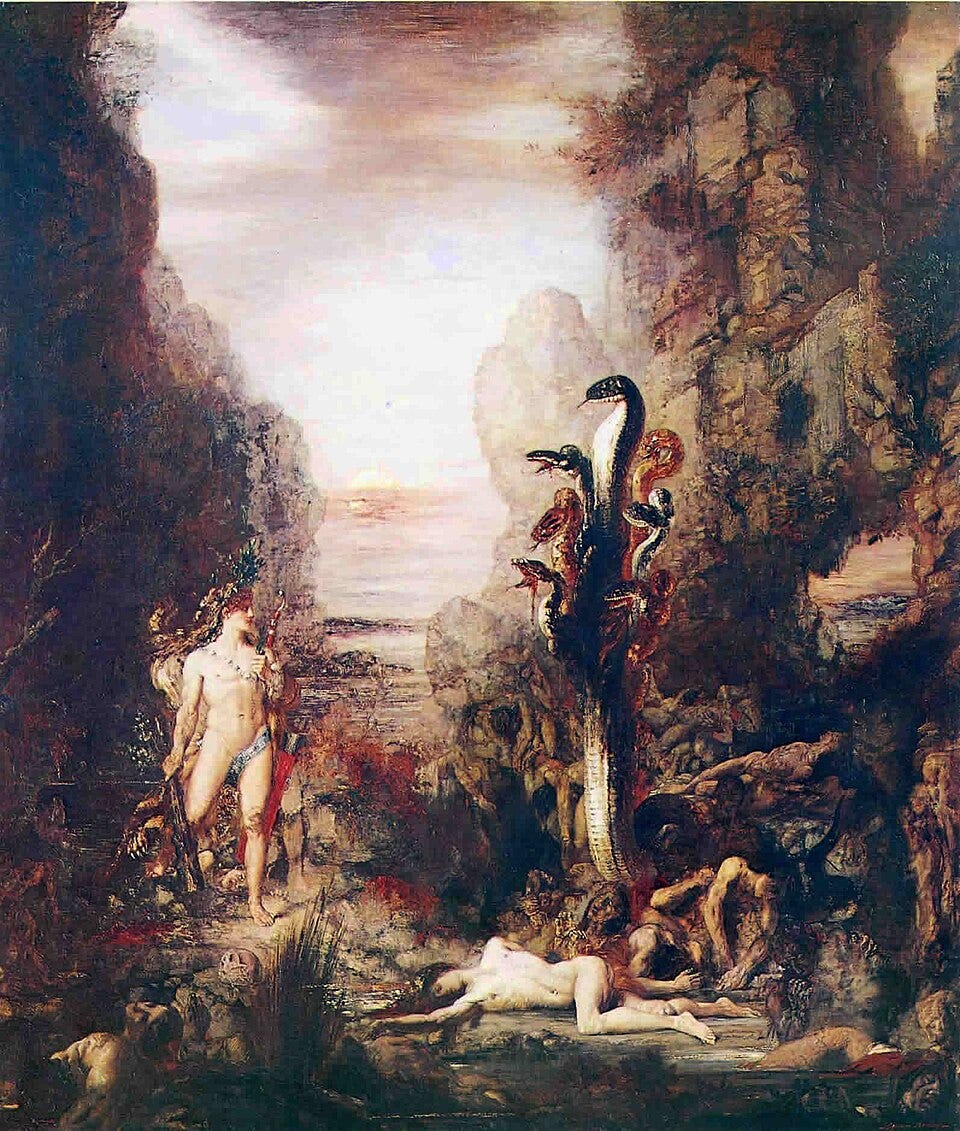

Gustave Moreau’s Hercules and the Hydra dates from 1876, and where the Englishman was neoclassic in his sculpture and painting, the Frenchman turned inward to phantasmagoric visions of the ancient world, becoming a major influence on popular fantasy illustrators of the 20th century, such as Frank Frazetta.

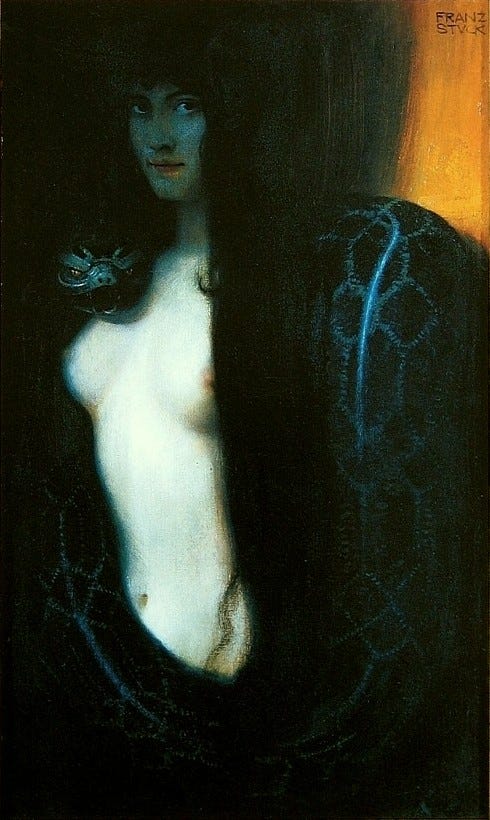

And finally, in the age of activist judges, mayors, governors, Congress members, journalists, professors — all of whom have one thing in common — we have the serpent of the Garden of Eden alongside its perennial ally, the femme fatale. “The Sin” was painted by the German Franz von Stuck in 1893 and requires no further explication.

Make no mistake, fearless reader: what you and your progeny — should you have any — face in the future is something the men of Europa have never faced before — at least not in 40,000 years or so. You must slay the “dragon” of the collectivist matriarchy and pave the way for superior heroes and kings to rise and usher in a reborn and ascending cycle of civilization. And for more on what to expect with that, see Erich Neumann’s 1954 opus The Origins and History of Consciousness.

Stay tuned for the next Decadent Chronicles as we explore more work from the visionary artists and writers who were first to explore the complex states of mind that emerge with consciousness of living in a declining age.

~

Christian Chensvold is a college fencing champion, third-generation astrologer, founder of Dandyism.net (2004), and author of The Philosophy of Style (2023) and Dark Stars: Heroic Spirituality in the Age of Decadence (2024). He is currently writing a work of 21st-century mythology, a Hyperborean Gothic fantasy that seeks to inspire Europa at the time of its greatest crisis.

Always good to see others appreciate von Stuck, he did a couple paintings using that theme and a large body of gorgeous work, loaded with esoteric symbolism. Amazing artist.

Also love to see mention of Levi and his influence. A self-taught scholar of incredible depth, surprisingly down to earth and really easy to read, especially Transcendental Magic.

Keep it up. Great series.