The West and Its Challenge: Part 1

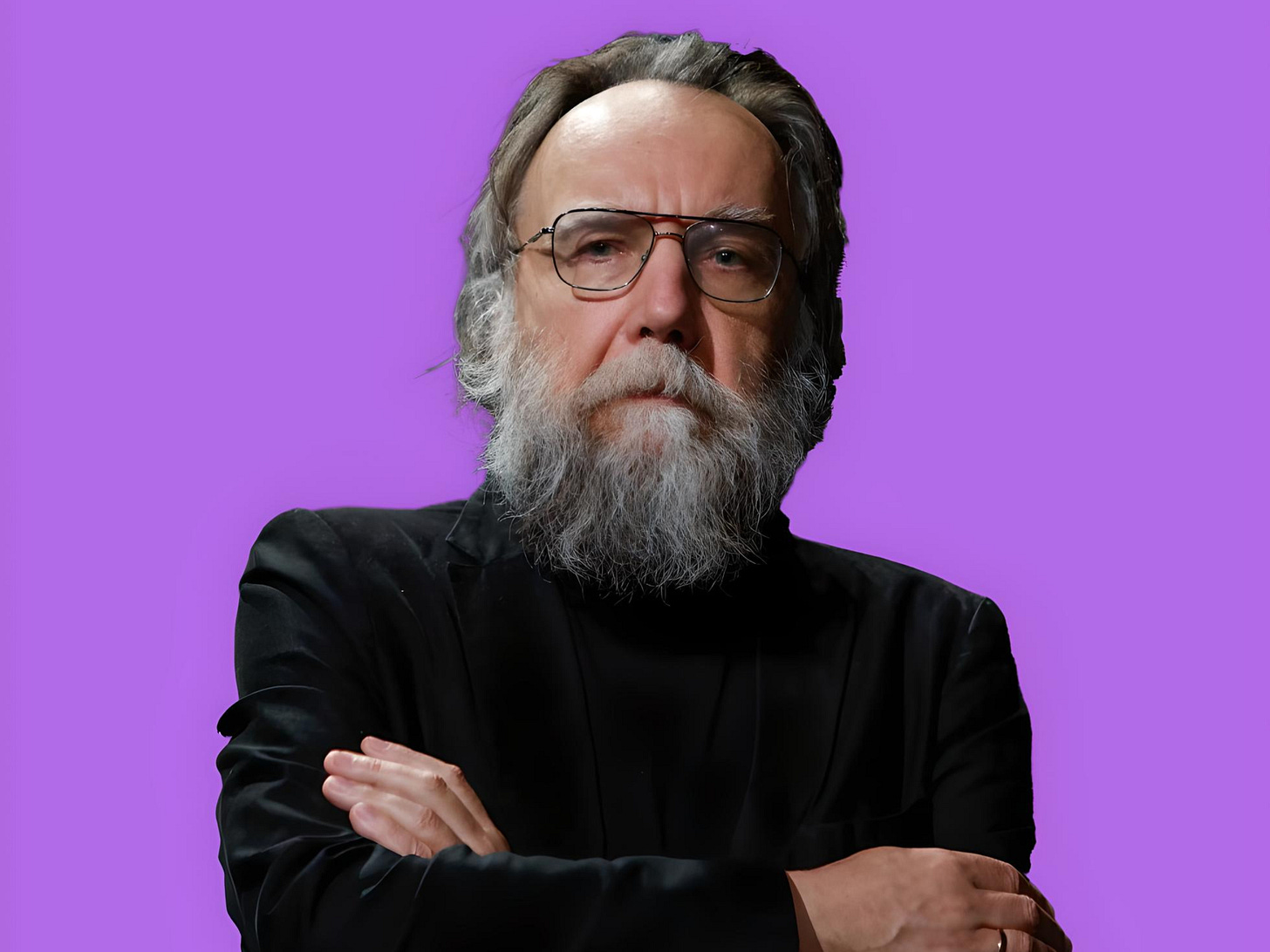

by Alexander Dugin

Alexander Dugin examines the historical evolution of “the West” beyond a geographical term to encompass Eurocentric perspectives and the broader implications of Western modernization and cultural dominance.

This is an excerpt from Alexander Dugin’s The Rise of the Fourth Political Theory (Arktos, 2017).

What Do We Understand by “The West”?

The term “the West” can be construed in different ways. Thus, we should first of all clarify what we mean by that term and examine how the concept has evolved historically.

It is perfectly evident that “the West” is not a purely geographical term. The sphericity of the Earth makes such a definition simply incorrect: what is for one point the West is for another the East. But nobody includes this sense in the concept of “the West.” On closer examination, however, we discover an important fact: the concept of “the West” takes by default as its zero-line, from which its coordinates are set, precisely Europe. And it is not by accident that the zero-line meridian passes through Greenwich, in accord with an international convention. Eurocentrism is built into this very procedure.

Although many ancient states (Babylon, China, Israel, Russia, Japan, Iran, Egypt, etc.) thought of themselves as “the center of the world,” “middle empires,” “celestial,” “kingdoms under the sun,” and so on, in international practice, Europe became the central coordinate.

More narrowly, Western Europe did. It is customary to set a vector in the direction of the East and a vector in the direction of the West starting from precisely there. Thus, even in the narrow geographical sense we see the world from a Eurocentric point of view, and “the West” at the same time presents itself as the center, “the middle.”

Europe and Modernity

In a historical sense, Europe became the place where the transition from traditional to modern society occurred. What is more, this transition was accomplished through the development of tendencies autochthonic to European culture and European civilization. Developing in a specific direction principles contained in Greek philosophy and Roman law, through the interpretation of Christian teaching — at first in the Catholic-Scholastic, and later in the Protestant spirit — Europe came to create a model of society unique among other civilizations and cultures. In the first place, this society:

was built on secular (atheistic) bases;

proclaimed the idea of social and technical progress;

created the foundations of the contemporary scientific view of the world;

developed and introduced a model of political democracy;

regarded capitalistic (market) relations as of paramount importance;

transitioned from an agrarian to an industrial economy.

In short, Europe became the territorial space of the contemporary world.

Because within the borders of Europe itself the more avant-garde areas of development of the paradigm of modernity were such countries as England, Holland and France, located west of Central (and especially Eastern) Europe, the concepts “Europe” and “the West” gradually became synonyms: the properly speaking “European” culture, as different from other cultures, consisted precisely in the transition from traditional society to the society of modernity, while this, in turn, occurred first of all in the European West.

Thus, from the 17th to the 18th centuries the term “the West” acquired a precise civilizational sense, becoming a synonym of “Modernity,” “modernization,” and “progress,” social, industrial, economic and technological development. From now on, all that was involved in the processes of modernization was automatically attached to the West. “Modernization” and “Westernization” proved to be synonymous.

The Idea of “Progress” as the Basis for Political Colonization and Cultural Racism

The identity of “modernization” and “Westernization” requires some clarifications, which will lead us to very important practical conclusions.

The issue is that the formation in Europe of the unprecedented civilization of the modern era led to a particular cultural arrangement, which at first formed the self-consciousness of the Europeans themselves and later also of all those who found themselves under their influence. The sincere conviction grew that the path of development of Western culture, and especially the transition from traditional society to contemporary society, was not only a peculiarity of Europe and the peoples that populate it, but a universal law of development, obligatory for all other countries and peoples. Europeans, “people of the West,” were the first to pass through this decisive phase, but all others are thought fatally doomed to go along the same path, because this is the supposedly “objective” logic of world history. “Progress” demands it.

The idea arose that the West is the obligatory model of the historical development of all mankind, and world history — as in the past, so in the present and future — was and is conceived of as a repetition of those stages that the West, in its development, already passed through or is presently approaching, in advance of all others. In all places where Europeans encountered “non-Western” cultures, which preserved “traditional society” and its way, Europeans made an unequivocal diagnosis: “barbarism,” “savagery,” “backwardness,” “absence of civilization,” “sub-normality.” Thus, gradually the West became the idea of a normative criterion for the evaluation of the peoples and cultures of the entire world. The further they were from the West (in its newest historical phase), the more “defective” and “inferior” they were thought to be.

The Archaic Roots of Western Exclusiveness

It is interesting to analyze the origin of this universalist arrangement, in which the stages of the West’s development are equated with the generally obligatory logic of world history.

The deepest and most archaic roots can be found in the cultures of ancient tribes. It is characteristic of ancient societies to identify the concept “human” with the concept “belonging to the tribe” or ethnos, which leads at times to their denying the member of another tribe the status of “human,” or placing him on an inferior level. By this logic, tribesmen from other tribes or enslaved peoples became the class of serfs, excluded from human society and deprived of all kinds of rights and privileges. This model — fellow tribesmen = people, foreign tribesmen = not people — lies at the foundation of the social, legal, and political institutions of the past, as was analyzed in detail by Hegel (in particular, by the Hegelian Kojève) through the pair of figures, Master-Slave. The Master was everything, the Slave, nothing. The status of human belonged to the Master as a privilege. The Slave was equated, even legally, to domesticated livestock or to an object of production.

This model of domination proved much more stable than one could have imagined. It moved on in modified form into the modern era. Thus arose the complex of ideas that paradoxically combined democracy and freedom within European societies themselves with rigid racist arrangements and cynical colonization in their relations with other, “less developed” peoples. It is significant that after more than a thousand-year gap the institution of slavery, what’s more, on racial grounds, returned in Western societies — in the first place in the USA, but also in the countries of Latin America — precisely in the modern era, in the era of the spread of democratic and liberal ideas. Moreover, the theory of “progress” serves, in fact, as a basis for the inhuman exploitation by Europeans and white Americans of aboriginals: Native Indians and African slaves.

It increasingly appears that by the formation of the civilization of the modern era in Europe, the model of the Master-Slave was transferred from Europe itself to the rest of the world in the form of colonial policies.

Empire and Its Influence on Contemporary Westernization

Another important source for this influence was the idea of Empire.

Europeans explicitly rejected that idea at the dawn of the modern era, but it penetrated into the unconscious of Western man. Empire — both Roman and Christian (the Byzantine in the East and the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in the West) — was thought of as the Universe, the inhabitants of which are people (citizens), while those beyond it are “subhumans,” “barbarians,” “heretics,” “gentiles,” or even fantastic creatures: man-eaters, monsters, vampires, “Gog and Magog,” and so on. Here the tribal division between one’s own (people) and strangers (non-people) is carried over to a higher and more abstract plane: citizens of empire (participants in the Universe) and non-citizens (inhabitants of the global periphery).1

This stage of generalizing who is and is not to be counted a person can be looked at entirely as a transitional stage between the archaic and the contemporary West. After formally rejecting Empire and its religious foundations, contemporary Europe preserved imperialism by transferring it to the level of values and interests. Progress and technological development were henceforth thought of as a European mission, in the name of which a planetary colonization strategy was implemented.

Thus, having broken away formally from traditional society, the modern era transferred some basic arrangements of traditional society (the archaic division into the pair person/non-person on ethnic grounds, the model of the Slave-Master, the imperialist identification of its civilization with the Universe and of all others with “savages,” and so on) to the new conditions of life. As an idea and planetary strategy, the West became an ambitious project for the new establishment of a world government, this time dedicated to the “enlightenment,” “development,” and “progress” of all humanity. This is a kind of “humanitarian imperialism.”

It is important to note that the thesis about progress was not a simple cover for the egoistic predatory interests of Western people in their colonial expansion. Faith in the universalism of Western values and in the logic of historical development was entirely sincere. Interests and values coincided in this case. This gave tremendous energy to the trailblazers, sailors, travelers, and businessmen of the West to settle the planet. They not only sought profits, but also carried enlightenment to the “savages.”

Cruel robbery, cynical exploitation, and a new wave of slave-holding, together with the modernization and the technological development of colonial territories, together formed the basis of the West as an idea and global practice.

Modernization: Endogenous and Exogenous

Here we should make one important observation. Starting from the 16th century, the process of planetary modernization began to unfold from the territory of Western Europe. It strictly coincided with the colonization by the West of new lands, where, as a rule, peoples preserving the foundations of traditional society lived. But gradually modernization affected everyone: both Westerners and non-Westerners. Somehow or other, everyone is modernized. But the essence of this process remains different in different cases.

In the West itself — first of all in England, France, Holland, and especially the USA, a country built as a laboratory experiment in modernity on supposedly “empty land” — modernization is distinguished by its endogenous character. It grows from the consistent development of cultural, social, religious, and political processes contained in the very foundations of European society. This does not come about everywhere simultaneously and with one and the same intensity. Such peoples as the Germans, Spaniards, and Italians, with whom modernization proceeds in a somewhat slower rhythm than it does with their European neighbors from the West, lagged behind. Still, the modern era for European peoples ensues from within and in accordance with the natural logic of their development. The modernization of the countries and peoples of Europe emerges according to internal laws.

Developing from objective preconditions and corresponding to the will and mood of the majority of European people, it is endogenous.

That is, it has an internal principle.

It is a completely different matter with those countries and peoples that are pulled into the process of modernization against their will, becoming victims of colonization or else being reluctant to oppose European expansion. Of course, conquering countries and peoples or sending black slaves to the USA, the people of the West furthered the process of modernization. Together with the colonial administration, they brought out new orders and foundations, and also the technique and logic of economic processes, mores, social-political structures, and legal institutions. Black slaves, especially after the victory of the abolitionist North, became members of a more developed society (although they also remained second-class people) than the archaic tribes of Africa from which slave traders had taken them. The modernization of colonies and enslaved nations cannot be denied. Even in this case, the West proves to be the motor of modernization. But here the process can be called exogenous, occurring from without, imposed, brought in.

Non-Western peoples and cultures remain in the conditions of traditional society, developing in accord with their own cycles and their own inner logic. In them there are also periods of ascent and decline, religious reforms and internal discord, economic catastrophes and technical discoveries. But these rhythms correspond to a different, non-Western model of development, follow a different logic, are directed to different goals, and decide different problems.

The main feature of exogenous modernization is that it does not emerge from the internal needs and natural development of traditional society, which, when left to itself, probably would never have come to those structures and models that were put together in the West.

In other words, such modernization is coerced and imposed from without.

Consequently, the synonymous series modernization = Westernization can be continued: it is also colonization (the introduction of external authority). The oppressed majority of mankind, excluding Europeans and the direct descendants of American colonists, were subjected to precisely this violent, coerced, external modernization. It impacted the traumatic and internal inconsistencies of the majority of contemporary societies of Asia, the East, and the Third World. This is sick Modernity, the West as caricature.

Already in the 17th century European and American authors (in particular, Jesuits) posed the question of whether Native Indians belong to the native population of America, to humankind, or whether they are some sort of animal.