The Revelations of "Mein Kampf": A Self-Incriminating Portrait

by Dominique Venner

In this penetrating analysis, Dominique Venner examines Adolf Hitler’s autobiographical manifesto not as propaganda, but as an inadvertent confession. Venner’s close reading exposes how Hitler’s own words betray the fundamental weaknesses that would make him not a national restorer or builder of empire, but a destroyer of civilizations.

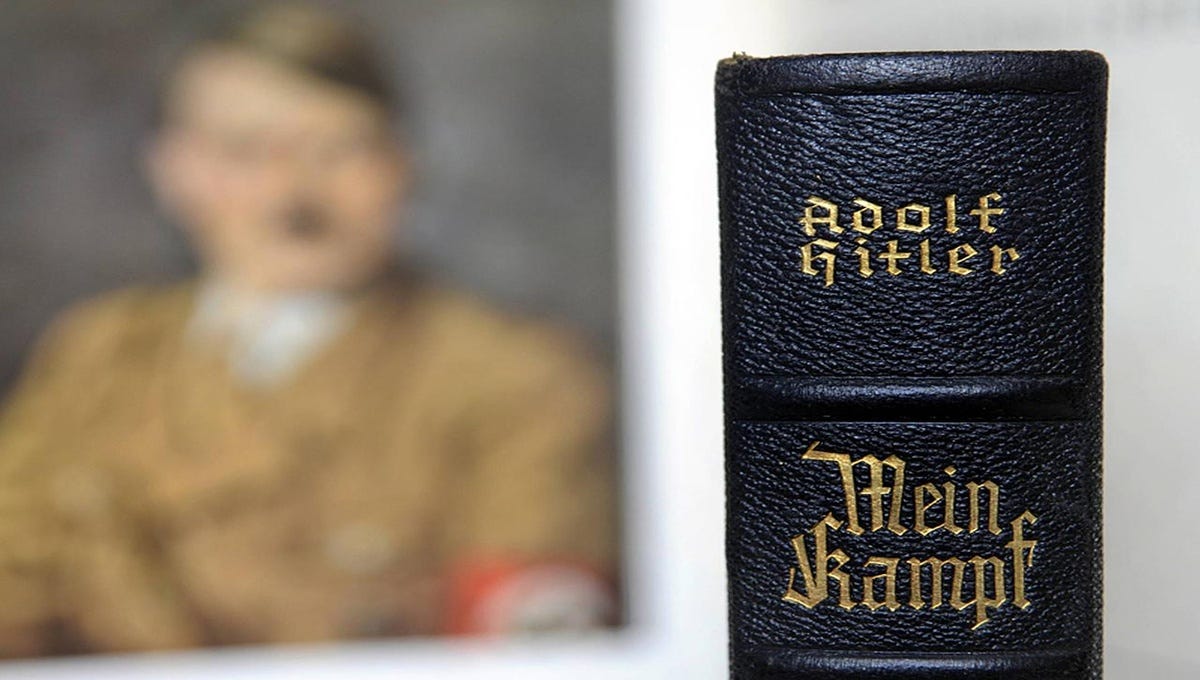

A crucial historical document, Mein Kampf is always invoked without being read. Yet it is an extremely revealing read. Hitler does not emerge from it enhanced. But the mystery of his character is largely elucidated.

What is the guiding principle of an action? This is always a question that the historian should ask, without it always being easy to answer. At least in Hitler’s case, we have a precious document for this purpose. Provided we know how to read.

The French edition of Mein Kampf has 686 pages.1 It brings together in a single volume the two books written respectively in 1924 and 1926. These dates are important. Their author is still very far from power, but everything is said about the methods he will later use to achieve his ends in foreign policy. We hold here a sort of indisputable blueprint of what his future action will be, without it being possible to accuse his adversaries of disinformation, since it is he who speaks in complete freedom, for the use of his supporters.

Hitler is 35 years old when he writes the first volume in prison, and 37 years old for the second, the one that details his expansionist views. He is therefore a mature man who does not have the excuse of youth. On the essential points, his ideas will no longer change. The character has been shaped by several exceptional ordeals. First, that of misery and hunger in Vienna, from the end of adolescence, during the years of his initiation to life and politics. These form the subject of the most engaging pages of a book that is often repugnant and poorly written. Then follow four appalling and intoxicating years of war in the infantry on the front lines, which make Hitler a new man. As with so many others of the same generation, they have forever tempered the implacable hardness of his worldview.

After the shock of defeat and the revolution of 1918-1919, he finally received, in the overexcited Munich of the ‘20s, the revelation of his aptitudes as a tribune and political leader.

The mental portrait that emerges from the book is that of an exceptionally gifted agitator2, an inflexible and imaginative revolutionary, but totally devoid of the superior qualities of a statesman. One understands that nationalist and responsible Germans who had the curiosity to read this enormous pamphlet at the time would have nourished the darkest forebodings about what would become of Germany if Hitler ever came to power.

Throughout the pages, the profile of a fanatical and intractable personality emerges, one that feels invested with a providential mission. One perceives a peremptory spirit, closed to all critical reflection, while his unilateral views, notably in foreign policy, are often of obvious poverty. In the development of international relations, beyond an obsessional antisemitism and a pan-Germanism inherited from the 19th century, he is guided above all by a sort of crude Darwinism. It is for him an article of faith that war necessarily selects the best and most fit. It does not occur to him that mechanical power can turn against human quality to the point of crushing it.

If war, as in the 17th century, seems to him the privileged means of great politics, the conquering ambitions revealed by Mein Kampf are, however, more modest than is generally said. Hitler does not dream at all of extending Germanic dominance over the world. His ambition is only to give Germany a “dimension of world power” analogous to that of France or England. Up to that point, there is nothing that is not legitimate. It is the means envisaged that are less so.

To judge by his book - without speaking of what his future action will reveal - this man so versed in the art and use of propaganda for internal use that he seems to ignore or disdain its effects in relation to foreigners. Similarly, he despises in principle negotiation or cunning (not to mention patience and prudence) as so many morally degrading procedures, which he will nevertheless happen to use with success. The only instrument he seems to recognize is “the sword” (a word that returns with pleasure under his pen). It is therefore by war and war alone that he seems to want to erase the injustices of the Treaty of Versailles3 and conquer in the East a “living space” necessary for the dignity and survival of the German people.

What about France in all this? In Hitler’s eyes, it is “the mortal enemy, the implacable enemy of the German people.” On this point, one must indeed recognize that he has excuses. In the aftermath of 1918, successive French governments did everything to acquire a reputation for implacable hostility. At the time Hitler was writing his book (1924-1926), Germans of all opinions were stirred up with anger and indignation against the “diktat” of Versailles, against the attempts to annex the Saar and the Rhineland, against the occupation of the Ruhr which devastated Germany in 1923. The fact that the French troops, which would occupy the Rhineland until 1930, include African contingents is felt as a deliberate humiliation and as a threat of racial pollution. Yet, against France, despite his invectives, Hitler in Mein Kampf shows surprising moderation on the substance. He envisages no other vengeance than future diplomatic isolation, thanks to Italy and England who, so he says, would be Germany’s only potential allies.4 This proves that this “fanatic” is not blind and is not indifferent to the balance of forces, even if he is mistaken in his evaluation.

In a formula that remains insufficiently known, he condenses with clarity the fundamental choices that will guide his future European policy: “We deliberately erase the orientation of pre-war foreign policy... We stop the eternal march of Germans toward the South and West of Europe, and we cast our gaze toward the East” (p. 652). Once the heavy dispute of Versailles is settled, he will therefore abandon any territorial claim against France, even concerning Alsace and Moselle, which removes the causes of conflict between the two nations. On the other hand, he conceals nothing of his design to conquer lands in the East, notably in Russia, by force. On this question, he knows that he will encounter in Germany itself the opposition of nationalist circles faithful to the Russophile tradition of Prussia.5 So he covers them with sarcasm, which reads today with lugubrious irony, knowing what became of his dreams of Oriental conquest for Europe.

The terribly determined prophet that the reading of Mein Kampf reveals is nevertheless neither unintelligent nor uncultured, but his mind is locked in a framework of indestructible prejudices. He is as narrow-minded as he is obstinate. While his vision of things shows evident deficiencies, one feels that he will always refuse what does not come from him.

We can cite three samples of deficiencies among others. Not for an instant, for example, does this curious revolutionary glimpse the opportunity to offer other peoples a project capable of rallying their support. The only perspective he grants them in his book-program is submission to the German master, in which he will, moreover, be at odds with the increasingly Europeanist sentiment of the new generations of his country.

In the field of foreign policy means, he cannot rise above the impressions left by the war. He does not imagine that certain essential things cannot be obtained by violence. With his gaze fixed on the statue of Frederick the Great or Bismarck, he sees only the roar of their cannons and the heroism of their grenadiers, forgetting their political finesse and their prudence disguised by audacity. Thus, it is only from a reconstituted German army, supported by a nation at the height of its form, that he expects everything and the impossible. To accomplish what he believes to be his mission, he never designates in his book any other means than those of constraint and arms.6

This surprising prophet of an Aryan revival will ultimately be its negator and gravedigger. Negator since he wants to be an exclusively German nationalist of the narrowest species. Gravedigger since, in his short-sightedness and his impatience, he denies what must be inscribed in the duration of centuries, and instead chooses to play everything in a sort of apocalyptic “all or nothing” that will leave behind him only ruins delivered to triumphant enemies.

After such a reading, and abstraction made of the sequel of history, one better understands the early opposition of an Ernst Jünger and the sibylline pages of The Marble Cliffs, which, in the face of the unleashing of destructive powers, invoke recourse to the superior forces of the spirit.

Originally published in Enquête sur l’histoire no. 28, September-October 1998.

Translated by Alexander Raynor

Buy Dominique Venner’s books

Nouvelles Éditions Latines, Paris 1934.

What he says about crowd psychology has lost none of its interest.

Finally, war will not be used, the threat having sufficed, except for Danzig, which will trigger the Second World War.

In the ‘20s and ‘30s, Italy and England indeed disapproved of the policy of force practiced by France against Germany. It is surprising that Hitler did not understand that England would modify its position as soon as a revived Germany would appear as a dominant continental power.

Question evoked in Dominique Venner’s book Histoire d’un fascisme allemand, les corps-francs du Baltikum (Pygmalion, 1996).

One will say that in this he is only imitating, for example, Louis XIV, so admired by French nationalists. In fact, pressed by Louvois, the great king had always privileged force. This is why he put the kingdom in danger during the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1713), and aroused in Germany, by the sack of the Palatinate, resentments that remained vivid in the 20th century. Still, the France of Louis XIV was a power proportionally superior to the Germany of the 20th century. The Europe of that time had nothing to fear from other continents. Border rectifications did not inflame non-existent national passions. The great hecatombs born from the industrialization of war had not begun. Which amounts to saying that the systematically brutal and arrogant policy of a Louvois, which was already a mistake in the 17th century, appears as a crime and an aberration in the 20th.

I am still waiting for someone reading Hitler as a savior of its people. Trashing Hitler is quite easy and in accordance with the jewish propagandists.

Venner is illiterate or a lackey. MK was a world best seller. NSDAP in all States never below 95% support. Arktos useless.