The Other Gramsci

by João Martins

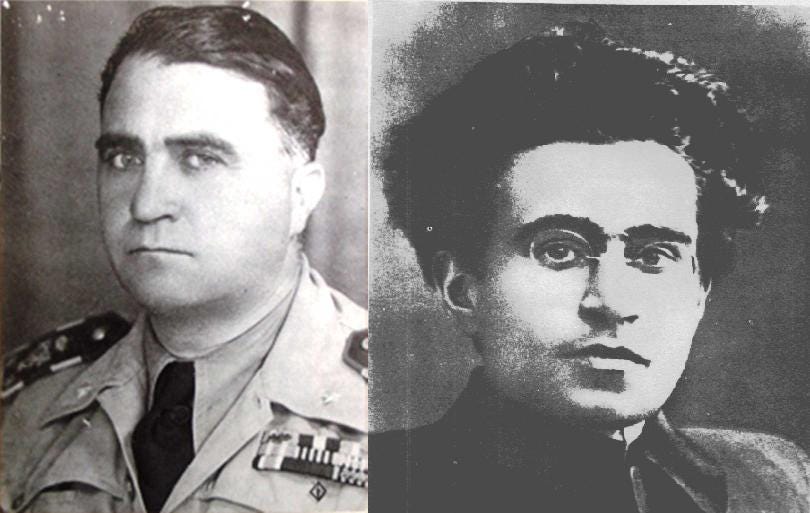

João Martins remembers the famous Italian Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci’s forgotten brother, Mario Gramsci, a devoted soldier whose adventurous life embodied loyalty, courage, and the tragic fate of Europe’s civil wars.

Beyond ideological leanings, we admire men and women who have devoted their lives to an ideal. Without such lives, experiences, and decisive acts of will or courage, any conception of the world becomes utterly devoid of humanity — of the faces, feelings, and emotions so often carried to astonishing levels of intensity that they result in the most tragic human dramas. Civil wars represent the culmination of such dramas, for no family escapes seeing its members on opposing sides of the barricades.

Recently, in my wanderings through modern European history, I came across a most curious episode that deeply moved me — an episode that occurred in Italy during the first half of the twentieth century, or, to be more precise, during what the German historian Ernst Nolte called the Second European Civil War.

I wish to share with you the fate of a man who bore a well-known surname, yet whose memory political circumstances consigned to the shadowy oblivion of history. I take this opportunity, therefore, to rescue from the dimness of time the recollection of a life, a damnatio memoriae, and to sketch, however briefly and thus unjustly, his extraordinary biography.

Antonio Gramsci, the well-known Marxist thinker and theorist of Cultural Hegemony, was a captive of the Fascist regime that nonetheless allowed him to continue his ideological work while imprisoned. He died 70 years ago. We may feel some sympathy for the man, or even study his intricate thought; yet no biographer could attribute to him what makes a human life richer and more beautiful — the spirit of adventure, of self-denial, that rebellious impulse to march against the current, or simply to be the family’s “black sheep.” The latter phrase fits most aptly here, evoking the black shirt of the Fascist squadrons — the very shirt that Antonio’s brother, Mario Gramsci, wore proudly, and in which he knew how to live and how to die.

Born in 1893 into a humble family, the youngest of seven children, Mario Gramsci did not live a long life, yet his days were filled with deep feeling and fervent patriotism — a life so intense it could have been taken from the Italian Futurist Manifesto, that famous diatribe by Marinetti against timidity and conformity, which exalted “love of danger, the habit of energy and daring (…) courage, audacity, rebellion.”

In the fateful year of 1914, the First World War began — a conflict that would bloodily close the door on the imperialist delusions of the 19th century. At 22, Mario Gramsci enthusiastically supported Italy’s entry into the war in 1915 and volunteered for the front lines, where he fought as a lieutenant. When the conflict ended, Italy found itself plunged into a deep political and social crisis.1 The so-called “mutilated victory” and the rising tide of communist agitation led him to join the newly formed Fasci di Combattimento of the veteran socialist agitator and fellow ex-serviceman Benito Mussolini. He soon rose to the position of federal secretary of the Fascio of Varese, and not even the persistent pleas of Antonio Gramsci and the rest of the family (Mario was the only Fascist among them) could dissuade him — not even the savage beatings he received from his brother’s communist comrades, which sent him to the hospital.

Antonio broke off relations with him in 1921. Nevertheless, in August 1927, at their mother’s request, Mario sought to reconcile with Antonio — by then imprisoned in San Vittore — in an attempt to help him with his legal troubles.

In 1935, Italy declared war and invaded the Kingdom of Abyssinia. Once more, Mario Gramsci volunteered to join the Italian expeditionary corps that would conquer Emperor Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia — a fierce nine-month campaign that allowed Mussolini to proclaim from Palazzo Venezia the birth of the Italian Empire.

By 1941, amid the Second World War, driven by his warrior spirit and now aged 47, Mario — who viewed life as a permanent battle — returned to Africa, this time to face the British forces threatening Italy’s possessions in Libya and what was then Italian East Africa.

As the war progressed, the Axis powers lost the initiative, and the tide of conflict turned decisively in favor of the Allies. In 1943, defeat upon defeat followed; part of Italy’s mainland was invaded by Anglo-American troops. Discontent spread through the Grand Fascist Council, and Mussolini was dismissed by King Victor Emmanuel III and subsequently arrested. Soon after, on September 8, came Badoglio’s betrayal: Italy surrendered to the Allies and declared war on the Third Reich.

Amid the chaos, Mario remained steadfast, his faith in the Fascist creed unshaken. Mussolini, freed from captivity by an SS commando, declared on September 23 the establishment of the Italian Social Republic — the short-lived yet infamous Republic of Salò. Instead of welcoming the invaders with white flags, or in some cases red or even American ones, Mario Gramsci answered the Fascist call to continue the fight, enlisting in the armed forces of the RSI.

Captured by the partigiani, the Fascist Gramsci was handed over to the British and deported to a concentration camp in faraway Australia. The harsh conditions he endured — a form of inhuman treatment reserved especially for unrepentant Fascist soldiers — gradually destroyed his health.

Released at the end of 1945, he returned to Italy only to die, as the injuries sustained in the camp proved irreversible. He was admitted to a poorly equipped hospital, where he passed away at the age of 52, in the presence of his wife Anna and their children, Gianfranco and Cesarina.

As a point of irony, it is worth noting that Antonio Gramsci, when he fell ill in prison due to a chronic disease contracted in his youth, was released and, as a free man, was able to receive treatment — at the expense of the Fascist regime — in a private clinic.

Mario’s name was never given to any street, unlike that of his brother Antonio, and he has been all but forgotten in the unjust pages of history. Yet Mario — the Gramsci in a blackshirt — remains undoubtedly the very image of the adventurer: an example of courage and loyalty, the glorification of the political soldier. Perhaps the words of John M. Cammett best capture the emotional richness of Mario Gramsci’s life: “He was a volunteer in World War I, a volunteer in the Ethiopian war, and again in World War II (at the age of 47!). And in between these disasters he was an enthusiastic volunteer to the very ideology which did him in! What a life!”2

Although a victorious nation, Italy did not see the full implementation of the treaties that would have granted it additional territories and economic benefits.

John M. Cammett, “Antonio’s “other” brother: A Note on Mario Gramsci,” International Gramsci Society Newsletter 7 (May, 1997) [http://www.internationalgramscisociety.org/igsn/articles/a07_16.shtml].

muy bueno

Interesting article. Didn't know this.