The Metaphysics of the Mask

by Askr Svarte

Askr Svarte sheds light on the transformative nature of initiation, the concept of masks in ancient rites, and the theater of the soul, revealing how the mysteries invite one to experience divinity and self-realization beyond societal roles and mortality.

Excerpt from Askr Svarte, Towards Another Myth: A Tale of Heidegger and Traditionalism, trans. Jafe Arnold (PRAV Publishing, 2024).

A person who goes through an initiation ritual becomes twice-born. Their first birth from their mother and father is not enough; they need to be born not only into society, but also into a name and status in view of the spirits, ancestors, and Divinities. The death of a faceless, nameless boy or girl, still shrouded by suspicion over whether they are humans and the community’s own or foundlings left by spirits, is an obligatory part of the trial and path to rebirth. Initiation is the primary social and sacred axis.

A special role in the spiritual realization and, by all accounts, the soteriology of the ancient Greeks was played by the mysteries, the closed sacraments for those who are already initiated. So much has been said about the mysteries that there is no need to dwell on their various aspects here. But it still remains worth emphasizing the extreme importance of being initiated into them, which elevated the neophyte into communion not only with a circle of others like him, but with the fundamental, root myth and literal miracle. The initiate took upon himself the strictest vow to keep the secret of the mystery, so we know very little about the inner aspects and deeds of the mystery apart from reconstructions. In other cases, the mysteries became a phenomenon of such significance that they were completely equated with the cults of Deities and even whole cities, such as Eleusis, or they were subjected to large-scale persecution, like the Bacchanalia in Rome.

Eleusis became the archetype of the mysteries par excellence, and it is Eleusis that is of great interest to us here. The core of the Eleusinian cult was a mystery that is clearly of agrarian origin, connected with fertility, the afterlife and rebirth, and the myth of Hades’ abduction of Persephone. The most important symbol was grain, a barley spike or wheat, the fields of which surrounding Eleusis were used to prepare the intoxicating drink known as kykeon.

Persephone was the daughter of Demeter and Zeus. When Persephone went missing, her mother, the Deity of fertility, fell into a great sorrow that caused the cessation of growth and harvest in the world. In this plot, we see traces of the archaic motif of a female Deity who simultaneously gives life and brings death, like earth that gives rise to shoots and swallows bodies (like seeds). As the mother mourned her daughter, Eleusis became a place of suffering and sorrow. When a long crop failure and lack of seedlings threatened the world with death, Zeus intervened and brought Persephone back from the underworld, having reached an agreement with Hades that his wife would spend six months with him and six months in the world of humans.

Karl Kerényi honed in on this myth as the most important nerve of the mystery revealed in the central room of the Eleusinian temple that was closed to everyone else. According to Kerényi, the essence of the mystery was a visual demonstration of the miracle of the emergence of life from death, of how “death gave birth.” After having become the personification of barren, dead earth, Demeter once again spread her shoot, i.e., death gave birth, just as a grain dies in order to provide space for germination. According to one theory, the initiate was shown the miracle of germination and the swelling of the ear of wheat. Nor should we lose sight of the psychedelic effect associated with ascesis before the mystery and the consumption of the ritual kykeon drink, which was brewed from wheat grains and mixed with wine. According to yet another version, ears of corn were an important part of the recipe. In any case, the sacred drink should not be interpreted as a profane or purely “mechanical” explanation of the mystery as something illusory, something imagined only in a state of delirium and intoxication. This approach is completely irrelevant. Sacred inebriation plays a definite and immense role in archaic traditions and often acts as a gate, bridge, or conductor to states and knowledge that have a completely different nature and source than the drink itself.

The Eleusinian mysteries bore a vividly soteriological nature: those who were initiated no longer feared death and knew of the rebirth of the soul. It is no coincidence that one of the main roles played in the mysteries belongs to the Deity of death, Hades, whose actions trigger the chain of events that conclude with the mysterious revelation of the consoled Demeter. Translated from Greek, the name Ἀΐδης means “invisible,” “unseen.” As already mentioned, it shares the same root as the word ἰδέα, that is the visibility of form, an image. Hades is the unseen Deity whose essence is to hide, to conceal the dead and Persephone, whose mother cannot find her due to her non-presence, her absence from the middle world. Hades was sometimes depicted as having his face turned away, or without a face altogether, which emphasizes his “non-present” nature. Death, thus, is associated with absence — of the deceased and of growth, of new birth, of the juices of life. By kidnapping Persephone and taking Demeter from the world, Hades gained power over the world in holding back the sprouting of all plants, crops, fruits, and the births of all creatures.

But our friend Heraclitus left us with a strange passage in which he attributes the bacchic and phallic rampages of Dionysus to Hades himself, thereby literally identifying the two Deities with each other. In favor of this speak their common epithets, such as Eubouleus (“Good Counselor”) and Chthonos (“Underground”). Karl Kerényi adds some important indications: “In general, there was a close tie between the wild fig tree and the subterranean Dionysos: his mask was cut from its wood in Naxos. To this day the Greeks have a superstitious fear of sleeping under a fig tree. A wild fig tree designated the entrance to the underworld in places other than Eleusis.”1

Dionysus is the son of Zeus and Persephone under the name Zagreus, meaning that Hades is at least his uncle, which brings us close to the avunculate we have already encountered. In the Sisyphus, Aeschylus calls him the son of Hades. Dionysus Zagreus is also the patron of the mysteries. It was he who was taken by surprise by the Titans when he looked into the mirror, and later in the form of a bull was driven out, torn to pieces, boiled, and devoured by them.

Hades and Dionysus share an even deeper connection than the intersection of kinship and mythological lines, the semantic fields of life, death, and reigning or descending into Hades. They are connected by the problem of appearance, of guise, and of bringing an image to visible presence. In other words, if Hades is Ἀΐδης, the invisible, the unseen, the faceless, then Dionysus is the Deity of metamorphosis who manifests himself in an unlimited array of images and faces (Zeus, Cronus, the bull, lion, snake, baby, toddler, horse, the thyrsus, phallus, etc.) which figure as masks. Thus, the contrast between absence and excess is held together around an absent or inaccessible center. We do not see Hades because of his concealing, withholding nature which leads to fatal lack, and we do not see Dionysus because he has an extraordinary multiplicity of manifestations whose motley, carnival shapeshifting steals and carries away our attention.

Here, we arrive at one of the most important points: classical, ancient, European theater’s origin in the mysteries and in close connection with Dionysus. In the multifaceted phenomenon of theater, itself unique in the structure of the cosmos, what interests us is the realm of metamorphosis and the metaphysics of masks. The very word θέατρον is connected to θεωρία, “theory,” which means a spectacle, a site for beholding and contemplating.

In folk theater, which is connected with scenes from the mysteries and agrarian sacraments, the setting for the plot is everyday life: scenes were played out on the porch, in the street, in the market, in the yard, or out in the fields. Everyone took part in acting out and reciting the mythical stories and roles. Myth was revealed and reproduced directly in the fabric of life here and now in connection with the calendar cycles. More complex and refined theater is defined by the presence of a special site for the performance of comedy or drama (theater as topos) and the emergence of the figure of the spectator, the viewer, who contemplates the performance as a myth unfolding before him. On this point it bears recognizing the presence of a certain degree of alienation between the viewer and the action, unlike the archaic folk festival played out in the middle of the streets.

Normative of mature Greek theater was the location and architecture of the Theater of Dionysus in Athens, located on the southeastern slope of the Acropolis. Thus, in the very center of the polis, the focal point of power, there is an orchestra of metamorphoses and Dionysianism. Behind the orchestra and opposite the theatron is a special space called the skene, the place where, hidden from view (like the mysteries), the Dionysian metamorphoses of the actors’ changing masks and costumes took place. A little lower down the slope behind the theater was a separate sanctuary dedicated to Dionysus. A small altar to Dionysus, called the thymele, was obligatorily raised on the site of every theater.

Metaphysically speaking, the stage figures as the space for taming the dangerous elements of metamorphoses and polemos. In theater, the leading metaphor is shifted from war to play. We know metaphors of argument as play, war as a party, and stable phrases such as Endspiel, “theater of war” and the like from many languages and cultures. Through the metaphor of play and theatrical performance, the basic structure of the manifestation of the Divine as polemos is transformed into a play of comedy or drama. The Divine manifests itself in the world in a regime of duality and fragmentation into many (πολλα). War, play (the enjoyment of the Divine, cf. Indian Lila), and eros are essentially modes of dealing with pairs and multiplicities within the imaginaire of the Mind that is at once turned both to the world and towards the One. Here, theater acts as a mirror, or rather a fractal doubling of space where extremely serious plots of drama, tragedy, satire, farce, comedy, and eros play out — a space residing within the absolute Divine’s beholding of itself as, all at once, the spectator and the actor, the troupe, the director, and the surrounding world. The absolute Divine is the one that both hides itself and finds itself in the role of someone in the play that it itself imagines. Such, at least, is the structure of the whole manifest cosmos proposed by Kashmir Shaivism with its non-dual aesthetics and high theological metaphysics of theater.

It is worth noting, however, that unlike the authentic and original theater of Greece or the metaphysics of theater in Advaita-Shaivism, the Germanic-Scandinavian tradition never yielded its own theater out of its own soil. All the traveling troupes and later medieval folk-theatrical performances were taken from Greco-Roman culture. The Germanics do not have their own authentic theater and mask, although some moments and scenes from the Eddic ballads are quite amenable to the stage. For instance, scenes of feuds being resolved through fun and games of arguments, such as when Loki makes the vengeance-seeking Skadi laugh, are plots virtually ready-made for folklore productions. Moreover, the Germanics had a Deity who wore masks and concealed himself, and their myths are full of frequent motifs of shifting guises. But this metaphysics was not developed within the Germanic Logos, probably due to the emphasis on war, thinking, and then philosophy as the leading Germanic principles. In philosophy, meanwhile, the metaphor of theater is often used for discussing and identifying the ontological status of the actor and the “subject” as such within the framework of the relationship between actor and the role or mask they play and wear.

The word “mask” comes to us from the Romance languages (French masque, Latin masca) and from the Proto-Germanic *maskā, which has a common bundle of meanings: to cover, to hide, often with woven fabrics (cf. Russian maskirovka — “camouflage,” “military deception”). In the Germanic languages, “mask” also refers to dirt or a solution that is literally rubbed over one’s face, hence the modern English “grime” (from Proto- Germanic *grīmô), “grimace,” and the stable semantic reference to gloom and the ominousness of appearance in the word “grim” (Proto-Germanic *grimmaz — evil, creepy). In the Icelandic language and in Germanic-Scandinavian mythology, Grímnir, “the Mask-Wearer,” is one of Odin’s heiti. The Latin word persona, whose origin is unclear but probably has similar roots, means mask, character, or figure. The latter goes back to the Latin figūra, which means to give form, to distinguish contours, to give appearance (cf. linguistic de-finition).

The Russian word for mask, lichina, comes from the poetic Proto-Slavic *likъ (“face,” “form,” “image”). Lichina is a seeming appearance, a substitution for the face. Hence the legitimate interpretation of lichnost’ (“personality”) as a kind of social mask, a set of roles in the family, society, and politics, a place in a hierarchy, or the set and structure of a person’s individual characteristics, etc. Our lichnost’, our “persona-lity,” is our mask for being-with-others on the sociological dimension; it is a social appearance that we don like a mask, like the specific mask-object of folklore. Accordingly, any social personality or guise is always not our very own self, Selbst, but a bringing of some qualities to the fore while hiding others, i.e., a conscious caricature of our lichnost’. If we follow the path of definition further, then the recognition that the lichina, the mask or persona, is always not we ourselves, leads us to what in Eastern teachings is a most interesting conclusion: our ego or mind which we suppose to be our immutable “I” is merely one form of oblivion and substitution, a false selfhood, which in its vanity endlessly drapes over and diverts attention from our true “I.” In other words, even what we consider to be “undoubtedly ourselves” might very well be recognized to be one or another form of masque.

A character, a personage, only becomes real when the actor puts on the mask, comes into the role, and leaves his own “I” aside to give the persona full ontological status. The self under the mask is concealed, and it would be wrong to address it during the play, for then only the mask-personage is responsible for all the actions, words, and events. This is partly similar to the Advaitist description of the nature of the manifest world. In the theistic monism of Shaivist Advaita, there exists only one absolute reality: Shiva, Shiva’s consciousness. Accordingly, the cosmos and the manifold atmans exist only within his boundless imagination, within Maya. Insofar as Shiva is “absolute reality,” then everything he imagines is no mere phantasm of the mind, but is absolutely real by virtue of belonging to his consciousness. A special logic is manifest here. The manifest world is extremely authentic and real; it cannot simply be dispelled like mirages of hot air over the surface of a road, as other darshanas teach of the nature of the manifest world. The Divine is present in any moment of time, in any event, in any particular thing, and therefore immanent in each and every thing at once. The position, hierarchy, and status of the sacred, even when defiled, are given according to the plot, hence Advaita does not mean, and is not reducible to, any egalitarian decay and confusion, nor does it contradict the hierarchical structure of the cosmos.

It is precisely this dimension that we are dealing with in the mysteries, in the ritualized celebrations of folk theater as imitatio Dei, in the direct repetition of myth, when the living give up their places, bodies, hands, and faces to masks, to the personages and figures of spirits, demons, ancestors, and Deities. A genuine shift and replacement of subjects takes place in the middle world; enthusiasm in the direct meaning of being enraptured by the Divinities descends upon the actors, and the humans-as-actors disappear altogether in offering themselves up as the space for real and present theophany. But in order for this to happen, one must hide himself, put his self into the shadows, and become a clearing for the entry and action of the spirit, the being, the personage, or the Deity in oneself and through oneself. A mask, a metamorphosis, a change of identity is needed. Masks are found everywhere, in all corners of the earth, among archaic tribes as well as in classical civilizations; they have come down to us from the deepest antiquity and are one of the symbols of culture as a whole.

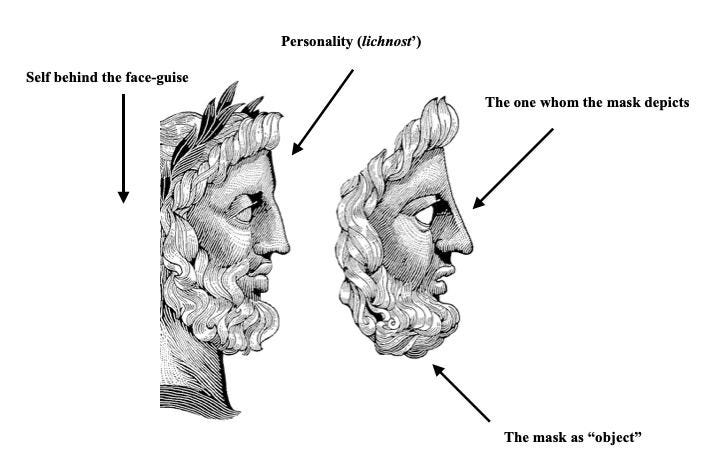

There are several scenarios at play here. First, giving up one’s place to the mask means concealing one’s personality (lichnost’). The personality in and of itself is a social mask which in some way reflects and in some way conceals our selfhood at its deepest core and as a whole. Thus, there is change in masks over the self. Second, the mask itself has duality, acting simultaneously as the new face of a personage (the one being depicted by the mask, on the obverse side) and as an object, i.e., the mask as a ritual thing which is in some sense like its empty reverse side into which we put our face. The craftsmanship of the mask does not matter — it can be ornamental, realistic, or simply a piece of bark freshly peeled off a tree with with eyeholes poked into it, or a clay cast hardened in the hands.

From here on out, the winding paths of the situations diverge. We know from traditional doctrines that a person’s deep identity is their Divinehood manifest within them in the middle world: tat tvam asi and the indistinguishable fusing of Atman and Brahman. When a person puts on the mask of a Deity, there can be an ecstatic implosion, a complete fitting and coinciding of the deep Divine self and the Deity on the outside, for the being of which man provides himself. But where and what are we ourselves in such a situation? We are in-between, like a permeable membrane, the Divinehood outside and inside. The ego-persona and the social mask-layers fall away, leaving us out in the open possibility of letting and releasing the Deity through us. One literally, physically feels like the reverse side of the mask of the Divine actor into which one inserts his “face.”

Metaphors of “nesting,” “interlayering,” “inputting,” reflecting, fractality, aporia, and recursion reign here. The mask acts as both the signifier (the symbol referring unto something) and as the signified (what the symbol refers to). Then, upon taking off the mask of the Deity, we return to ourselves as an individual personality (lichnost’), but on an even deeper level the very same Divinehood sees and speaks through us, like an actor through the mask’s empty eye sockets and open mouth.

The mask is Dionysus. Not the one who puts it on, and not the one whom it depicts, but the very boundary and event of metamorphosis. The situation is even more interesting when it comes to a mask that only hides, that doesn’t express anything, i.e., a faceless mask whose guise does not even refer to any anthropomorphic silhouettes. To whom or what do we present ourselves as chronos and topos (Zeit und Da) when putting on a faceless mask? Obviously, the leading motif here is the absence of any subject whatsoever. This leads us to two things: to the death of the subject, in which case the concealing mask is an alternative symbol of a burial shroud, a grave, Hades (and we might also mention pure corporeality, since the subject-ego is absent, leaving only the corpse), or, in the case of classic deixis, to the apophatic instance of the Nothing.

Finally, in modern conditions, we can raise the question of the metaphysics and ontological status of the person who wears a mirror mask which in form (figure) doesn’t express anyone, but which reflects absolutely everything. In this optic, the person and his I are concealed, but to whom and to what, to what personage, are being and subjectivity delegated? To none, for there is no subject, but there is the whole world that converges in the focal point of the mirror mask. Thus, in there is no-one and nothing in the center, but around it absolutely everything is reflected and unfolds.

Classical as well as extravagant masks depicting no-one or a mirror still belong to the register of beings, i.e., they “are,” even if only as indications of absence. Moreover, in language and speech we can draw a direct analogy between masks and metaphors, kennings, symbols, and names. On the whole, the word is also a mask, and a mask is a symbol, and it follows that it belongs to the order of language.

The situation is manifoldly complicated in theology, for all the names of the Divinities, all of their theophanies, descriptions, epithets, guises, stories, deeds, and myths are all sets of masks which have been seen, heard, perceived, and placed on altars by people across different cultures. There is no point in drawing any analogy with the vulgar argument that “man invented the Divinities,” for the emphasis has already shifted to how the Divinities or the Divine have in all times remained concealed, while on every altar or in every cult and mystery stands a mask, beautifully decorated in mythos and with a deictic sign in the form of holes for the eyes and mouth which point to the apophatic dimension.

The pantheon of Divinities is a circle of masks which the ineffable and unknowable Divine tries on and, upon choosing one, in an absolutely credible and fully-fledged way becomes it, i.e., becomes a specific Deity and its mythos that fascinate peoples and enchant unions of epopts.

People peer into the masks of the Deities and put them on. The Divine also peers into its masks, but, unlike man, puts it not on its“face,” but onto everything exterior, simultaneously creating this exterior and leaving the center empty. This is somewhat similar to the notion of how a Deity manifests itself in the world and in so doing renders itself manifest (ποίησις), reflected in nature, traditions, language, and the people who invoke, pray to, and praise it. The Divinities, then, are in essence Being’s visions of itself in various mythos-generating manifestations. From here we come to the recognition that all being(s)-as-a- whole (Seiende-im-Ganze, the cosmos, totally everything) is, in the light of any monistic ontotheology erected around and from any known Deity, none other than the manifestation of one or another mask. The world, nature, and we ourselves are a mask turned around and facing us. The faces and enigmas of the Divine are the manifest world. But this cosmic mask hangs over the void of the Nothing. In Russian folklore, there is the beautiful riddle of the “masked faceless,” to which the response can only be recursive: it is an “enigma,” a “riddle.”

The mask, the concealing-unconcealing play, is, for instance, the faithful conviction in the distinction between atman and Brahman. The metaphor of matter and Maya as a veil attains theatrical dimension not only as the curtain, but as the fabric covering the self. At the same time, everything extant thrown on top of and projected over the Nothing, with all the filigree- carved patterns of natures and the fates of people and peoples, points to the Nothing itself like a mirror.

To return to the image of a reflective mask on this ontotheological and metaphysical level, if we move from exterior “objective nature” to its “subjective” source-center, then we once again discover only its reflection. In the best case, we understand that this reflection is a reflection onto something, and then we’ll be dealing with the figure of a Deity hidden by and within the world. All traditions and religions dwell on this point in speaking of a supreme Father-Deity or a Divine Mother and their offspring kin and humans. The light of the glory of the Divine outshines, and thus obscures, any suspicion as to the masquerade character of all being(s), even if it unfolds as a fully-fledged, credible, real and present drama within the world.

When the mask is removed, the world literally disappears. Fear of death is fear of the mask that the Divine removes in order to put it in front of itself and to look (theoresis—teatron) into its empty eye sockets where its eyes used to be. Meanwhile, the human being looking into the mask’s empty eye sockets sees himself as the Divine contemplating itself from out of the depths.

Purchase Towards Another Myth here.

Carl Kerényi, Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, trans. Ralph Manheim (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), 35-36.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were based on the inclusion of "organic-LSD" in the Kykeon -- provided by ergot-mold grown on the temple's "First Fruits" harvest. This ingredient, like its synthetic follow-on, caused an experience of death-then-life in the Tellesterion ritual, producing the Athenian committent to immortality. Which is why Leary used the "Tibetan Book of the Dead" as his guidebook.

This "spicing" of the barley-beer drink has been widely documented, particularly in 1978 "The Road to Eleusis," the publication of which was delayed until Kyrenyi had passed in 1973, so as not to embarass him. More recently, this "psychedelic" understanding has become a best-seller, through Brian Muraresku's 2020 "The Immortality Key."

A Eleusis Kykeon était l'ancêtre du LSD.