Read, Choose, Fight!

by John K. Press

John K. Press traces his political shift from “culturism” to White Christian nationalism, challenging readers to contemplate their own political positions against the backdrop of societal upheaval and the quest for identity.

My previously published and upcoming Arktos books provide readers with a spectrum of political views because they show my personal continual political movement rightward. In doing so, they aid readers in clarifying where they stand and to where they might move politically. Desperately needing clear, strong, viable, and motivating political visions, these books serve a vital purpose. Early in my political authorship, I promoted “culturism” as the opposite of, and antidote to, multiculturism. This work sought to return our institutions to promoting pride in, and assimilation to, our Christian heritage. Yet, in the introduction to my 2007 pre-Arktos book on the topic, I explicitly argued that arguments based on race and IQ could not lead to any good results. Rather, by just taking diversity seriously, seeing our culture as unique and others as profoundly alien horrors, I argued that we could restore morals and justify immigration bans. And, as patriots come in all colors, promoting Western cultural pride could bring about cultural unity democratically and peacefully.

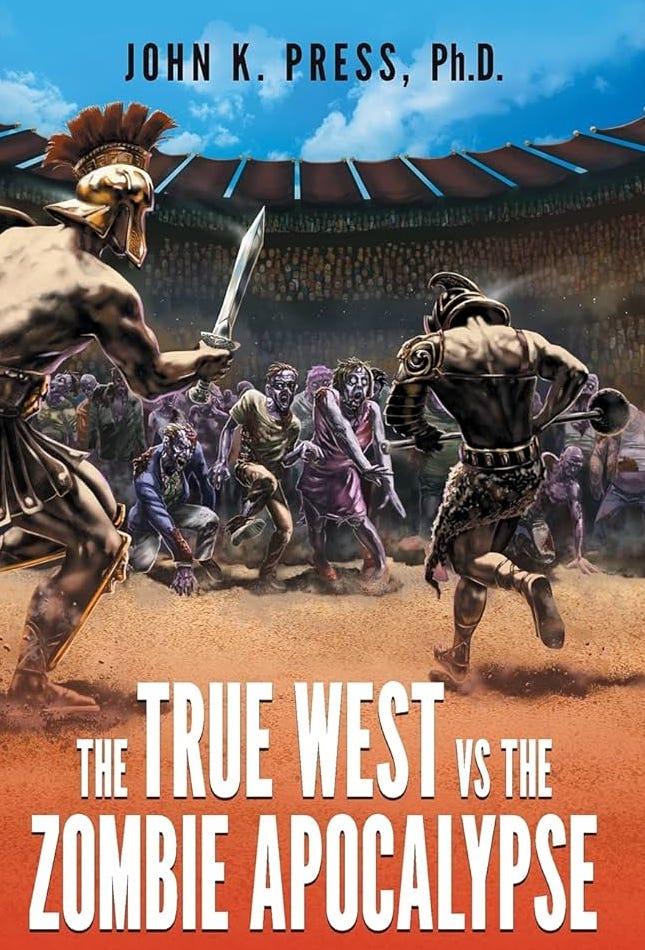

My first Arktos book, The True West vs the Zombie Apocalypse, in thrilling fictional form, shows a character who quickly evolves away from this culturist position and ends up promoting White Christian nationalism. As Zombie Apocalypse opens, the lead character has written a book on Cultural Nationalism, mirroring my old ‘culturist’ position. But changes begin when cell phone use and low IQs start to transform New York residents into zombies. The policies of killing and segregating zombies evolve. Racial IQ differences being what they are, nearly all blacks and browns turn into zombies. Yet, herein we only see a quasi-racist position because some low-IQ Whites also turn into zombies. Therefore, those opposing our lead character could not strictly call his policies “racist.” And, as the debate about such policies happens in a democracy, needing the black vote means our lead character could not advocate strictly racist policies.

Segregation creates a sustainable pause in Zombie Apocalypse’s political evolution. At this juncture, the lead character moves to a small town in Oregon. Herein, we explore a variation of the political program of Russell Kirk, who advocated a return to “the Permanent Things.” In this town, the tie to blood, community and place dominates. Herein, people make their own homes, grow their own food, marry and have children locally. We need to overthrow our corrupt global governing systems. We need a return to “Permanent Things.” But it is unclear how much of modern liberties, technology and commerce we should reject. Sadly, Kirk’s vision makes for a great life, but does not deter threats well. Suddenly, in the story, paralleling real-world realities, we learn that the segregated zombie masses will not stay in their place. Outside forces organize them and begin to attack human civilization. Thus, the lead character has to leave his local, rural, aspirational dream village and go to war against immediate threats.

Before bringing the remaining largely-White human population to battle, our lead character must unite and toughen up his population. Herein, one of my favorite transformational scenes happens when the lead character subdues the leftist rebels. We cannot debate them; we must embrace our sense of domination; the argument becomes, “join now or die now.” That’s a strong authoritarian brand of culturism. Relying on White history, our human heroes build a string of colosseums and stage gladiator battles so that we might regain our ethic of killing and subduing our enemies. Herein, thus far, we have seen free White “small-r” republics and extreme collective pagan militance as solutions. To complicate matters, this pagan militance organizes under a Christ Militant banner. All this challenges the reader to define what they consider a workable post-revolution social ethic. But, as we must know, this fictional population has to get hardened immediately to fight their apocalyptic battle against zombies.

After the war, we have Kirk’s proposals mixed with Christian Nationalism, in the shape of a locally strong and militant Christian theocracy. Reaching the culmination of this book’s political trajectory, herein White nationalism finally gets represented. A monarch not needing the black vote, our leader can simply implement policies that maximally benefit Whites; the few remaining non-Whites get exiled. And, herein, we come to the point wherein my upcoming Arktos book begins its march down the political spectrum. Entitled A Call to Arts, this survey of White art history, from cave paintings to modern times, uses our artistic history as evidence of the racial superiority of Whites and of Whites’ right to supremacy on their own lands. It promotes holy veneration for our artistic relics, which will also boost reverence for ourselves and our lands. In this context, A Call to Arts also extensively documents the negative impact Jewish art critics have had on White Christian culture. And, as an art book, it considers and recommends the use of Nazi symbols and aesthetics as powerful tools. Policy implications lie downstream of this recommended aesthetic shift. Herein we have another form of peak right to consider.

After we retake our lands, White lands cannot return to Weimar-style decadence. But what version of White culture to install? Some still advocate Zombie Apocalypse’s initial position: a meritocracy that explicitly acknowledges racial IQ differences, leading to de facto segregation. But the war on Whites has also made it obvious to most of us that we must also, at least, explicitly acknowledge Whites’ existence and right to supremacy on White lands. My art history book argues that Whites should start their public reassertion of control over their territory from art museums and churches. It also shows how these institutions’ interiors convey mores, both pagan and Christian, local and collective, that can still guide Whites to solvency. Some might argue rural White villages will naturally embody ‘Permanent Things’ without cultural coercion. Personally, as my books exemplify, I believe Whites need to move radically rightward collectively, with coercion. At the very least, we now urgently need a core of revolutionaries to fight for White supremacy. And this group should fight with shared aspirational goals. The spectrums in my published and upcoming Arktos works aim to aid this White core in defining the White race’s immediate needs and long-term goals. Hopefully, even this short article itself also glimpsed at touchstones you felt inclined to reject or consider. Please do so with passionate conviction.

'Christian Nationalism' is an oxymoron. Christianity is anti-nationalist, if by 'nation' you mean a people with enough shared ancestry to allow them to recognize that shared ancestry. 'Christianity' is race-communism. A White Christian will always prefer a non-White Christian to a White Pagan because, once you allow your consciousness to be colonized by abstract loyalties (like 'Christianity' or 'Yahweh'), you stop caring about 'nation' and are solely motivated by those abstraction.

I recently rewatched Aronofsky's 'Noah' and every time I do, I sympathize with Tubal-Cain more and more. If you eliminate the magical elements from Aronofsky's tale, and see Noah as a man willing to kill *everyone* because his 'god' tells him to do so, he seems no different Tubal-Cain, except Tubal-Cain doesn't pretend he gets his instructions from 'God'.

White Christians are a minority now in the Christian community.

Eventually, that's going to bite 'Christian Nationalism' on the ass.