Fire on the Megamachine!

by Alain de Benoist

Alain de Benoist examines how contemporary society is experiencing a profound "loss of the world" through the systematic elimination of diversity, ambiguity, and meaningful distinctions. Drawing on four recent books, he argues that beneath visible crises like immigration and cultural decay lies a deeper problem: the dominance of economic forces and technological acceleration that reduce everything to uniform, quantifiable, and interchangeable elements. The essay traces how this "Ideology of Sameness" manifests through the disappearance of ambiguity, the compulsive drive toward mobility, and the contemporary embrace of excess that ultimately leads to nihilism and the forgetting of authentic human being.

From the Polytheism of Values to Global Uniformity

Behind the visible crises of our era — immigration, educational collapse, moral decay, tyranny of the Same — lies a deeper evil: the programmed dissolution of all form, all limits, all distinctions. Four recent essays allow us to probe the deep mechanisms. In Towards a Univocal World, Thomas Bauer diagnoses the disappearance of ambiguity. Jacques Dewitte, in The Texture of Things, dismantles the ideology of indifferentiation. Christophe Mincke and Bertrand Montulet, with The Society Without Respite, explore the ideology of mobility. Finally, Alain Coulombel, in his Short Treatise on Excess, describes contemporary hubris as the founding principle of a world without borders or compass. Four angles risking the same conclusion: the loss of the world.

Immigration, educational collapse, criminality, wokeism, single-minded thinking, however condemnable and harmful they may be (and they are), are never more than epiphenomena whose profound cause must be sought in a social structure permeated down to its most elementary forms by a dominant ideology bearing nihilism and chaos. This is why, even if these phenomena did not exist, or disappeared tomorrow, current society would remain a thoroughly harmful society - not to say an enemy society.

Several recent books which emphasize certain major characteristics of current society invite the reader to examine three of them in depth: the loss of diversity and the tendency toward indifferentiation, the acceleration of mobility, the omnipresence of excess.

In an essay that enjoyed great success upon its publication in Germany, Thomas Bauer, professor at the University of Münster, takes a fresh look at the first of these tendencies, the most visible and undoubtedly also the best known, namely the reduction of diversity, both that of wild, domestic or agricultural species and that of peoples, ways of life, languages, cultures and rooted customs, which are so many essential foundations of the living.

The Ideology of the Same

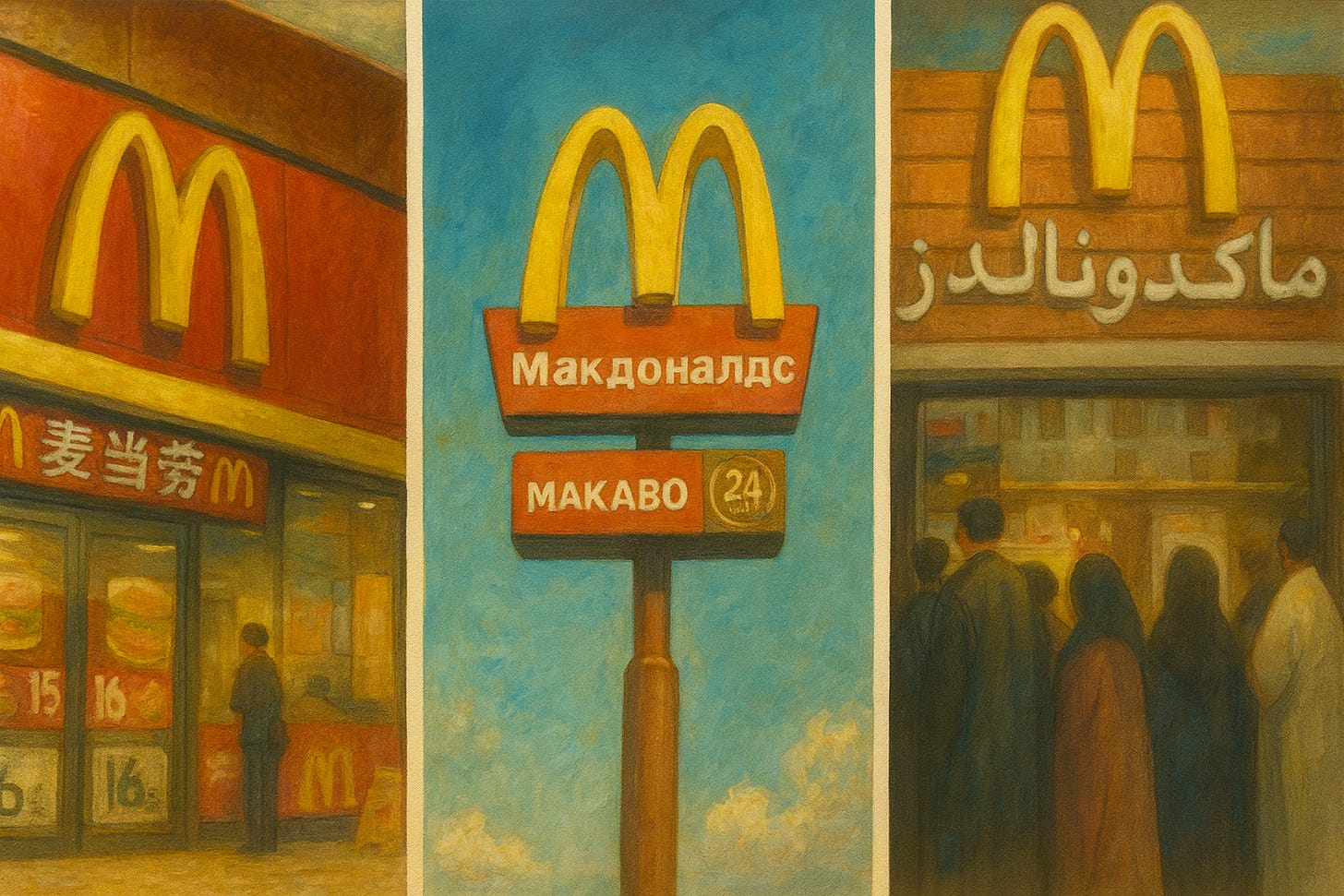

On the material level, this uniformization can be observed as soon as one travels and looks around: everywhere "non-places" multiply, similar functional locations (highways, shopping centers, large hotel chains, airports, supermarkets, etc.), which create "neither singular identity, nor relation, but solitude and similitude1." These are the new wastelands. Added to this is a uniformization of imaginaries within nations and civilizational areas: in France, apart from climate, gastronomy and folklore consumed by tourists, regions have almost totally lost their personality. From one end of the world to the other, we see the same films, hear the same songs, manipulate the same screens, belong to the same "social networks," drink from the same information sources. Languages become impoverished and accents disappear.

The loss of diversity is part of a homogenization process that never ceases to accelerate. It engenders a uniformization of the world and a massification of behaviors that go hand in hand with the commodification of social life. There is a uniformization of concepts on one side, and the progressive homogenization of reality on the other - without it being possible to say which is the driver of the other. But one must not be mistaken: if, from one end of the Western world to the other, objects, living spaces, and even ways of seeing the world increasingly resemble each other, if they no longer distinguish themselves according to their identity, destination or purpose, it is because those who shape them have the conviction that humans themselves resemble each other more than they differ, so that ultimately they are the same everywhere, which makes them interchangeable. The dominant ideology is, first and foremost, the ideology of the Same.

The phenomenon is not new, and many observers have noted it, generally to lament it. Think of Paul Valéry who wrote in 1925: "Interchangeability, interdependence, uniformity of customs, manners, and even dreams, are gaining the human race. The sexes themselves seem no longer destined to distinguish themselves from each other except by anatomical characteristics" (Valéry could not yet imagine the destitution of sex in favor of "gender"!). Stefan Zweig, at the same time, similarly denounced the "monotony of the world": "The customs proper to each people disappear, costumes become uniform, customs take on an increasingly international character. Countries seem, so to speak, no longer to distinguish themselves from each other, men bustle and live according to a single model, while cities all appear identical [...] Unconsciously, a single soul is created, a mass soul, driven by the increased desire for uniformity2."

The Becoming-Univocal of the World

Thomas Bauer's originality is to insist on a fundamental point often overlooked: the allergy to ambiguity that is gradually imposed around us. One would be wrong to consider this a detail. It is, moreover, not by chance that Zygmunt Bauman saw in ambiguity "the only force capable of containing and defusing the destructive, genocidal potential of modernity3." It is therefore a lock to be broken.

To qualify the loss of ambiguity, Bauer uses the word "univocity" (Vereindeutigung). The becoming-univocal implies a refusal and an increasingly accentuated intolerance towards everything that is ambiguous, plural, unclassifiable, contradictory, or simply nuanced: the ambivalence of feelings, the ambiguity of amorous games, sensitive reason and conflictual harmony, humor, second degree, shimmering beauty, the polytheism of values, the polysemy of symbolic thought, the variegation of being.

Words henceforth must be unidirectional, at the cost of a narrowing of the range of meanings in a Manichaean world that - even when it claims the rainbow! - no longer tolerates anything but black and white, a world for which everything that escapes ready-made classifications, all transversal approaches, all contradictions joyfully assumed of existence, everything that in a word is consubstantial with nature, language and human life, is denounced as "confusionism": it is "not clear," therefore it is suspect (and whose game is one playing?). Watchword: Who is not with me is against me! The foolish demand for "transparency" goes in the same direction: one must track down the opaque even under the sheets. Added to this, finally, is the generalized suspicion, which a morality police makes great use of, knowing well that today accusation equals condemnation (one is condemned from the moment one is accused, according to the principle that there is no smoke without fire!).

Reduced to the univocity of their sole commercial value, art, religion, science, and politics lose their intrinsic value. This can be observed in all domains4. Since Descartes, truth increasingly merges with univocity, the certum with the verum, power with the reduction of uncertainty in favor of geometric, numerical, mathematical, economic and techno-scientific certainty. "Everything that does not appear univocal,” writes Bauer, “everything that is charged with ambiguity [...] everything that cannot be quantified, is devalued. But as this induces little social cohesion, another instance takes power. It is the market, endowed with the magical capacity to attribute an exact value to an ever-increasing number of things."

Modern society is indeed hostile to any human activity that is not productive, that is ultimately not economic and cannot be the subject of a quantified calculation. Decision-making by machine is also necessarily univocal - the new version of the liberal slogan "there is no alternative" (Margaret Thatcher). "It is only too naive men,” said Nietzsche, “who can believe that human nature can be transformed into purely logical nature."

Towards a Uniformized Egocentrism

Note that identity itself is not univocal. To plead for a univocal identity, to believe that identity implies unicity, to conceive it as a unidimensional essence, is to make a deadly concession to the proponents of the Unique.

Jacques Dewitte, collaborator of the Revue du MAUSS, also addresses the problem of indifferentiation, but from a more philosophical angle. To the indifferentiation of a world without consistency, he contrasts the "texture of things," relying notably on Aristotle, Hannah Arendt, and Adolf Portmann, but also on the work of architect Léon Krier.

"My hypothesis,” he writes, “is that there was something like an original decision, a first ontological choice of the West, both Greco-Latin and Judeo-Christian, concerning the way of seeing being in general; a decision in favor of differentiated forms against the representation of a real supposedly constituted ultimately of a unique elementary substrate, of which differentiated forms would be only simple states, pure inconsistent appearances."

There was, in other words, a cultural and socio-historical choice in favor of true diversity, visible, changing, plural, of the phenomenal world, as opposed to the entropic uniformity that reduces (and ultimately destroys) differences. It is this choice that has been called into question, first by nominalism, then by the religious or secular individuo-universalism that constitutes the bedrock of the dominant ideology.

The temptation of the undifferentiated, explains Dewitte, is a form of attraction to entropy, that is to say to death. What Husserl called the "life-world" is not composed of abstract elements, apprehensible by analytical rationality, but of concrete things (natural or artificial): things are not pure objects, but indeed the "substance of the world" (Christian Norberg-Schulz). We see them and recognize them as we recognize a face. The recognizable forms of things are that by which the world comes to meet us. The original given is doubly given: insofar as it is there, and insofar as it is a gift. This suffices to reject all metaphysical dualism, whether positivist or, on the contrary, Platonic, both of which postulate a radical separation of the intelligible and the sensible on the grounds that essences belong to a "back-world."

Jacques Dewitte emphasizes that in the world of the undifferentiated, things are reduced to their functions5, and shows how the rise of indistinction and the grayness of uniformity are favored by "the logic of radical individualism which leads to mass conformism, where each believes himself different while in fact all resemble each other." This is what Milan Kundera already said when he spoke of "uniformized egocentrism6." Indifferentiation actually entails a derealization of the perception of the world, a "loss of the world" that affects everyone.

Hybridization and “Bougisme”7

The praise of all hybridizations ("mixingism") goes in the direction of indifferentiation: by dint of merging colors, only one remains: gray. The same goes for the "fight-against-all-discriminations," which leads to the abolition and fluidification of all distinctions, starting with the distinction between sexes, which Shulamith Firestone proudly makes the "final goal of neo-feminism."

The apologetics of the mixed-race as well as of the transsexual are both supposed to demonstrate that nothing stable exists in nature ("there is nothing precise in nature," the reason being that "everything is in perpetual flux," Diderot already wrote in The Dream of d'Alembert). "The world hybridizes, objects hybridize, identities or cultures hybridize, disciplines hybridize. Hybridization could well become the dominant norm," writes Dewitte. Identity itself becomes experimental, reversible and provisional. Hybridization announces the interchangeable. Everything was already in Magritte's famous painting representing a pipe: "Ceci n’est pas une pipe."

The struggle for or against differences is as old as the opposition between the sophist Antiphon, who privileged the elementary over form, and Aristotle, who privileged form. It is the contrast between image and concept, concrete and abstract, durable and ephemeral, intensity and extension, rootedness and nomadism, between the somewhere and the anywhere, between anchoring and universalism, but also between those who accept the world as it is and those who want to "correct" it according to an idea of what it should be.

Christophe Mincke and Bertrand Montulet address another problem, that of mobility. This is another well-known fact: modernity has gone hand in hand with unprecedented mobility. But it is not enough to recall that it was in modern times that the car, airplane, steamship, and rocket were invented, that we now endeavor to constantly break speed records, that the ever-increasing rapidity of information has resulted in "zero time" (the same information is given worldwide at the same instant), that mass tourism is a modern phenomenon, that travel has taken on essential importance in the lives of our contemporaries, that we already count 700,000 "mobile workers" in France, etc. The important thing is to note that mobility owes everything to the injunction to move. This injunction to mobility is already contained in the liberal principle demanding the free circulation of men, goods and capital ("laissez faire, laissez passer"), which amounts to positing that borders must be held as non-existent, in which it is inseparable from a progressive ideology that sees in "bougisme" (Pierre-André Taguieff) an excellent way to delegitimize anchoring, rootedness and, more generally, everything that is of the order of the sedentary, local or permanent.

Acceleration

What the book brings out well is the "emergence of a mobilitarian ideal based on the valorization of mobility for itself." The fundamental idea is that, in the current world, mobility has become an end in itself. One must move, one must stir, because movement is life, because it allows access to the happiness of being everywhere and nowhere at once - and especially because it dissuades from being from somewhere. Mobility "is no longer something that allows reaching an objective. It has become a good as such”8. It is an obligation that imposes itself on all.

Mobility is the negation of the axiom according to which men only move if they must, their natural state being a certain fixity. "In the current context of nomadic metaphysics, it is indeed no longer legitimate to claim immobility. Can one imagine today a worker claiming attachment to a single employer? A wife affirming her eternal fidelity to her spouse?" References themselves become erratic and moving, commitments drift away.

Speed, in this perspective, becomes synonymous with power, progress, results, records. We "move" faster and faster, because speed accentuates mobility. Mobility puts man in orbit, the model being the machine that never stops. "When the tempo accelerates [...] when, under the effect of market economies, everything seems to move at once and very quickly, nothing resembles anything anymore, however, O paradox! everything resembles everything," Philippe Ariès had already noted9. This role of speed and acceleration in the history of modernity has been well studied by Paul Virilio and by Hartmut Rosa10. Mobility accelerates the changes that the ideology of progress, which is based on contempt for the past - which represents a mutilation of collective memory, but also makes "memorial" commemorations insignificant - and considers them positive for the sole reason that they give birth to the new (innovation being also valorized in and of itself).

Disaffiliation and Disanchoring

Mobility is therefore far from being reduced to freedom of movement. Its greatest consequence is the upheaval of our relationship to space and time. We have moved from ways of life endowed with their own rhythm to "mixed" ways of life marked by the rapidity of successions of movements and their multiplication through long-distance communication. This is the advent of the flux-form, as opposed to the limit-form, which triumphs in the "liquid" (or "maritime") society of screens and networks11.

The change in our representations of space-time does not only concern the way reality is perceived within social forms, but also implies a modification of social prescriptions, that is to say normative constructions guiding action and thought. Mobility, in other words, is not only a movement, but also a social construction, a normativity referring to a particular conception of the world, which opposes mobilitarian discourse to anchoring discourse (the rhizome against the root), and aims to establish new relationships of authority, surveillance and control.

Paul Virilio had already remarked that "zero time" diminishes "three attributes of the divine: ubiquity, instantaneity, immediacy." Our relationship to politics, citizenship and territory is transformed by this crushing. "The compression of time,” writes Serge Latouche, “is a fundamental effect of the destruction of the concrete world caused by the productivism of the growth society." The obsession with "urgency" makes time the ultimate obstacle to overcome. To gain time is to gain money (time is money).

Total mobility has thus taken over from the total mobilization (Totalmobilmachung) of which Jünger spoke. Activity, incessant and exhausting, stressful and depressing, is no longer something one undertakes out of duty or to reach a particular telos, to realize or to realize oneself, it becomes a new nature. Henceforth celebrated as such, it represents the way man must, to survive, put himself in rhythm with a "world that moves." One must adapt to the job market, which implies moving, even expatriating (one flees a situation for another).

The potential for mobility now forms part of capital. Our social relationship depends on maintaining our performances, and not on occupying a position. Precarity becomes generalized, the "professional path" replaces the career, as "employment" replaces the trade. Bougisme obliges to embark on the mad race of the Megamachine, causing the resemblance of those who are in perpetual movement. Disaffiliation or disanchoring becomes an obligation, men are literally disoriented.

Just as it tends toward the suppression of borders, the mobilitarian ideal tends toward the negation of limits, both spatial and temporal. Every limit is indeed "considered as carrying unacceptable constraints on the entities confronted with it," with as consequence the appearance of a new constraint: always moving more, from which paradoxically results a new stationary state, like for hamsters that turn ceaselessly in their cage while remaining in place. "Man, integral part of this context, no longer has to distinguish himself from it, but to assume his belonging to an unlimited real."

The Gods Against the Titans

Alain Coulombel attacks the problem of excess in a "short treatise" that presents itself as a dictionary, with entries such as "accumulation," "extractivism," "megalopolises," "robotics," "total surveillance," etc. His postulate is that excess "is not simply of the register of excess, but stems both from transgression and more radically still from the refusal of all limits, a refusal which for Hannah Arendt defines the proper of human action."

The Ancients feared excess, the Moderns idolize it. "Just as in all arts the intelligent man submits to just measure, so also the good man must submit to the legitimate order of the universe," we read in Epictetus. The refusal of "just measure" is the very definition of hubris. A very old problem as witnessed, well before the advent of the megalomaniacal world of unlimited power, gigantism and "always more," the opposition of the world of gods (which is also the world of men) and the world of Titans (the Giants in Germanic mythologies). In the Gigantomachy, the Titans are on the side of brute elementary, of the formless, of disorder, of unleashed nature, while the gods are on the side of form and harmony. "If we always carry within us a part of barbarism, said Jean-François Mattéi, it is because our reason still preserves a part of the titanic12."

The man of Antiquity privileges finite perfection, Western man has the "itch of the infinite" (Nietzsche). Spengler was right to say that ancient culture and Western, Faustian culture are in many respects different cultures - and even opposite cultures. It is an error to believe that one constitutes the quite natural "sequel" to the other. Ancient culture is on the side of the gods, Western culture on the side of the Titans.

By realizing two great modern fantasies, that of self-generation, of the self-made man who constructs himself from nothing, and that of a world without body, that is to say of a disincarnated man, modern technology clearly stems from excess, at the same time as it corresponds to the supreme stage of reification, that is to say of the transformation of man into object. Thomas Bauer observes that "certain utopians already dream of a transhumanism or posthumanism where machine-men will finally be able to lead a life totally freed from ambiguity [...] When machines decide truth, we will finally be able to live freed from ambiguity." But he also sees in it a "negation of history," and it is undoubtedly on this last point that it is fitting to insist.

History, indeed, is by definition the domain of the unforeseen. The great characteristic of the machine is on the contrary that it is foreseeable. Machine-man becomes foreseeable to the very extent that he becomes machine, transforms himself into machine. The cyborg, man "augmented" by prostheses and electronic chips, then finds himself dispossessed of what makes his specific grandeur: his historicity.13 The great replacement of man by machine is therefore not only the promotion of a "world without qualities," but also and above all the advent of a being deprived of all access to Ereignis, to the capacity to "make happen in oneself, in one's property" (Heidegger).

Nihilism as Forgetfulness of Being

Technology is certainly inherent to the human condition because man is a "being of lack" whose tools are the true organs. But modern technology is quite another thing than the technè of the Ancients. Heidegger repeatedly reminded that the essence of technological is not technical but metaphysical in nature. This is why, if he often criticized modern technology, he also affirmed that it is by opening oneself to the essence of technology that one will be able to glimpse the "liberating appeal."

The current epoch represents a turning point whose only precedent is the Neolithic revolution. Confronted with the first farmers, hunter-gatherers had known how to maintain their preeminence by creating a functional hierarchized structure where agriculture corresponded to the "third function." What could be today the equivalent of such a transformation?

The loss of diversity, the role of mobility, excess: immediately, it is to the capitalist system that all this refers. Carried both by the death drive14 and by the autophagous logic of capital15, capitalism today reigns over a world transformed into "a universe of means that serve nothing other than their own reproduction and their own growth" (Zygmunt Bauman).

The great factor of homogenization is the primacy of economics and the planetary unleashing of the axiomatics of interest. Capitalism by nature aspires to the world market and demands the abrasion of everything that can obstruct the logic of profit. Flexibility, innovation, competition, adaptation, so many words that justify mobility, which perfectly satisfies the demands of a capitalism henceforth totally deterritorialized. Alienation is the fundamental characteristic of the capitalist mode of production. To be alienated is, in the proper sense, to be foreign (alien) to oneself, which is basically a form of madness: society becomes an asylum for the alienated.

For now, we live in the epoch of "the obscuring of the world, the flight of the gods, the destruction of the Earth, the gregarization of man, the hateful suspicion towards everything that is creative and free16." We live at the hour of the dissolution of grand narratives, of the dissolution of collective projects, of the dissolution of all form of us-ness (Wirheit). Nihilism always resides in the forgetfulness of Being: "To remain in the forgetfulness of Being, and to limit oneself to having to do with beings - that is nihilism." To get out of it, one would have to change superego. Replace the superego that alienates with a superego that incites overcoming. Failing that, we will continue to turn like rats in a labyrinth. Without finding the exit.

The four books that inspired Alain de Benoist’s essay:

Thomas Bauer, Towards a Univocal World. On the Loss of Ambiguity and Diversity, l'Échappée, Paris 2024, 160 p.

Jacques Dewitte, The Texture of Things. Against Indifferentiation, Salvator, Paris 2024, 208 p., postface by Fabrice Hadjadj.

Christophe Mincke and Bertrand Montulet, The Society Without Respite. Mobility as Injunction, Editions de la Sorbonne, Paris 2024, 180 p., preface by Vincent Kaufmann.

Alain Coulombel, Short Treatise on Excess: The Worst is Not Always Certain, Le Bord de l'eau, Bordeaux 2024, 226 p.

Buy Alain de Benoist’s The Ideology of Sameness

This essay was originally published in Éléments no. 215, August-September 2025.

Translated by Alexander Raynor

Marc Augé, Non-Places. Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, Seuil, Paris 1992.

Stefan Zweig, The Uniformization of the World, Allia, Paris 2021. Cf. also Olivier Roy, The Flattening of the World. The Crisis of Culture and the Empire of Norms, Seuil, Paris 2022.

Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and Ambivalence, Polity Press, Cambridge 1991.

An example: to serial music, of which he says that ambiguity is "totally absent," Thomas Bauer opposes the famous "Tristan chord" (F, B, D♯, G♯) which traverses all the musical drama Tristan and Isolde by Wagner, "typical case of an ambiguity of extreme complexity: superabundant plurivocity, without however being infinite or destructive of meaning, rationally analyzable without ever leading to a univocal result" (p. 74).

In their debate about secular religions, we know that Hannah Arendt reproached Jules Monnerot for affirming that things are above all defined by their function, an idea that led him to consider that a substitute, an ersatz, was not fundamentally distinguished from an original work if it could fulfill the same function. To which Hannah Arendt replied that when she used the heel of her shoe as a hammer, this did not transform this shoe into a hammer. In reality, definition proceeds on the contrary from distinction, which itself arises from an interrogation about what is. Things are defined by their substantial content, not by their function.

Milan Kundera, The Betrayed Testaments, Gallimard, Paris 1993, p. 275.

Translator’s Note: “Bougisme” is a term coined by the French thinker Pierre-André Taguieff. It does not have an equivalent English translation. In French, the verb bouger literally means ‘to move.’ Bougisme is a term to describe a degraded progressivism which effectively accompanies liberalism: the cult of change for change's sake. They have to move because the world is moving around them.

Cf. also Timothy Cresswell, On the Move. Mobility in the Modern Western World, Routledge, New York 2006.

Philippe Ariès, Essays of Memory, 1943-1983, Seuil, Paris 1993, p. 57.

Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics. Essay in Dromology, Galilée, Paris 1977; Hartmut Rosa, Alienation and Acceleration. Towards a Critical Theory of Late Modernity, La Découverte, Paris 2012.

Cf. Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Present, Seuil, Paris 2007. Cf. also Bertrand Montulet, Mobilities. The Spatio-temporal Stakes of the Social, L'Harmattan, Paris 1998.

Jean-François Mattéi, The Sense of Excess, Sulliver, Paris 2009. Cf. also Olivier Rey, A Question of Size, Stock, Paris 2014.

Cf. Denis Collin, Becoming Machines, Max Milo, Paris 2025.

Byung-chul Han, Thanatocapitalism, PUF, Paris 2021.

Anselm Jappe, The Autophagous Society, La Découverte, Paris 2017.

Martin Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics (1952), Gallimard, Paris 1967, p. 42.