Esotericism and Bauhaus Architecture: Part 2

by Michael Kumpmann

Michael Kumpmann explores how contemporary architecture — from the disorienting labyrinth of the Backrooms to Brutalism and glass-facade skyscrapers — manifests a postmodern condition of rootlessness, aesthetic dogmatism, and techno-cybernetic domination, revealing a civilization trapped in perpetual motion without purpose.

Read part one here.

The Backrooms: Pure Technical Functionality as Modern Hell

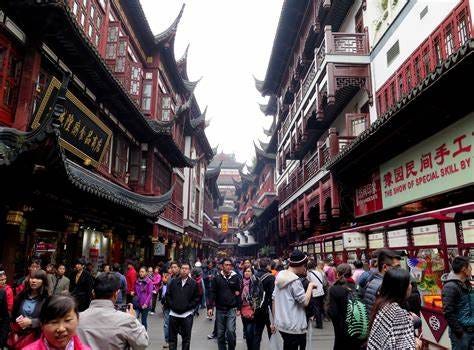

The Backrooms. A modern internet legend of a kind of hell made up of an endless office complex.

One aspect noted by Thomas Wangenheim and the YouTuber Schattenmacher is that the internet meme of the “Backrooms” actually represents the endpoint of the “form follows function” principle. The Backrooms are an internet phenomenon that began when someone posted a photo of an empty office space on 4Chan, which appeared slightly eerie. Another user then jokingly described the image as a photo from a parallel dimension. This parallel dimension — the so-called Backrooms — is a kind of hell that one can fall into from this world if a mistake is made, but from which escape is no longer possible. Once trapped in the Backrooms, a person is doomed to spend eternity in an infinite office labyrinth with no way out. This meme, which sounds like a cathartic outburst from a very frustrated office worker, grew into a massive internet phenomenon. People began seeking out other uncanny “liminal” images — like swimming pools with strange, large round windows or slides — and from these, built an internet mythology around this parallel world, including films, series, and video games.

The most obvious interpretation of the Backrooms, of course, is that they serve as a Kafkaesque critique of capitalism and the life of the modern worker. The hell of the Middle Ages was fire and brimstone. The hell of the modern age is the office.

Thomas Wangenheim and Schattenmacher add an important point here. The Backrooms possess the quality of being extremely disorienting to the human psyche, because they endlessly repeat the elements of that single office photo, turning it into a monotonous labyrinth. Individual locations become indistinguishable.

Another Dimension of the Backrooms

As René Guénon wrote, the fundamental principle of modernity is the standardization of things down to a small number of basic elements, which are then endlessly recombined. Every single part becomes interchangeable. Many modern office complexes are built precisely this way: a few patterns repeated ad nauseam. The Backrooms thus emphasize a trait that is already inherent in modern functionalist architecture — one that contributes to its disorienting effect.

Returning to the topic of monumental buildings, as addressed by Thomas Wangenheim: older urban design was meant to prevent such disorientation, and monumental buildings served this purpose. In cities, people could orient themselves because such landmarks were visible from afar, and it was easy to remember where something was in relation to a well-known building. (This principle, now used in video games and especially in amusement parks to guide visitors, is sometimes called “Disneyland navigation.”)

According to Schattenmacher, these liminal spaces also represent a form of “eternal progress” as “eternal motion without destination” — that is, movement for its own sake. (This thesis, again, echoes Mark Fisher’s idea of lost futures: we want progress, but since we can no longer imagine a future, progress becomes an end in itself — yet no one knows where we are actually progressing to.)

In the modern West, many people’s lives are likewise governed by a compulsion towards such “endless movement without a goal.” State ideology tells men that even being interested in women is “sexism” and “entitlement.” Citizens are told not to have families or children because the planet is overpopulated and having children is harmful to the environment. Instead, it is supposedly liberating and empowering to sacrifice one’s life for career, profession, and income. People are told to live only for themselves and their own material desires — because only then are they truly free. And even though they cannot pass on their earnings to anyone since they have no heirs and their money is quickly eaten up by inflation and other forces — and society does not truly care about them — they are still expected to earn as much as possible.

In a sense, the modern Westerner is already spiritually a prisoner in the endless labyrinth of the Backrooms, haunted by shadowy entities. With no goal and no place. Always on the run, always in motion. Concerned only with survival.

Postmodernity and the Collapse of the Ego

There is a second aspect here that ties into the “postmodern condition.” According to the psychologists Deleuze and Guattari, in postmodernity the human “ego” dissolves into cybernetic feedback loops and schizophrenic desire machines. The human being no longer has a coherent personality but only sub-personalities preoccupied with immediate gratification and the obstacles to it. According to Mark Fisher, the idea of the future disappears in favor of an eternal present.

In classical psychoanalysis, the “ego” is also the so-called “reality principle,” which not only justifies one’s needs but also weighs them against each other. While a “stubborn toddler” wants everything immediately simply because he wants it, an adult with a fully developed ego can balance his needs and forego present desires in order to gain more in the future. (Behaviorist B. F. Skinner thought along similar lines and proposed the classic experiment: “Here are two gummy bears. If you don’t eat any today, you’ll get four tomorrow,” as a way to measure a child’s mental maturity.)

Therefore: the loss of the ego (or the fact that it was never developed) in Deleuze and Guattari’s thinking is, psychoanalytically, the same as the “eternal present” in Mark Fisher or the “present preference” in Austrian economics. Thus, the chaotic, never-ending Backrooms become a symbol of postmodern madness itself and of the loss of the self. The monster eternally chasing one through the labyrinth is nothing other than one’s own instincts, gone out of control.

It is fascinating that real-world architecture is beginning to resemble the symbolic chaos of the Backrooms while simultaneously exaggerating technical rationality. At root, we are dealing with an excessive rationalization of technology, while humans themselves increasingly become completely instinct-driven, irrational hedonists. In a sense, our architecture reflects the fact that in postmodernity, man has sacrificed his brain to the machine.

The machines, in the postmodern age, begin to make intelligent decisions, while more and more postmodern humans stop doing so.

Nick Land: Cybernetic Loops in the Battle Between Tradition, Human Life, and Cybernetic Carcinoma

A street in Shanghai — a place that, according to Nick Land, is a social time machine, linking future and past.

And naturally, when everything becomes interchangeable, this also tells people that they themselves are interchangeable, able to be relocated to any arbitrary point even in their own hometown. According to Nick Land’s book Templexity: Disordered Loops through Shanghai Time, the city — and especially the modern city — is a cybernetic system that shuffles people and architecture as needed in order to produce the most growth and stability for itself. The modern city is a self-reinforcing process that partially escapes human control. And this labyrinthine, monotonous “Backrooms architecture” simply reveals to the individual how little control he truly has, and how much he is now at the mercy of the processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization.

In the same book, Nick Land also discusses the so-called International Style. To put it roughly, there was a trend in modern architecture to flatten culturally specific elements and visually harmonize systems internationally. This is the second aspect of the “form follows function” maxim. Modern city architecture seeks to grow. But to grow, it must — thanks to entropy — “devour” surrounding areas like villages or incoming migrants in order to obtain new material for reconfiguration. And this cold, function-focused architecture serves to strip the modern city of the natural limits that might otherwise prevent it from consuming such material.

An intriguing argument Land makes is that the resistance to this development — the desire for a “return to tradition,” as the internet puts it — actually stems from the same impulse as the process that turns architecture into an inhuman total machine. According to Land, the process of functionalist urban growth at any cost is also humanity’s struggle against entropy, decay, and death. (Here he is surprisingly close to Heidegger.) The city, in this view, exists to reverse decay and reverse time. Its drive for growth is its survival instinct as a system, and therefore a drive to rewind the time that would otherwise lead to its decline. Hence, culturally, the city is a kind of time machine.

And especially in architecture, the striving for tradition and its preservation is also the desire to maintain one’s roots — to create a legacy that outlasts oneself and stands tall and solar for eternity. This, too, is a struggle against entropy, decay, and death. It is the very same process that describes growth into the future.

That is why Nick Land believes that cities must always be both progressive and conservative at the same time. According to Land, the forward movement must eventually always lead to a movement backward in time. (As an example, he cites the theory of hypothetical tachyon particles that, after surpassing the speed of light, are said to gain the ability to travel through time.) Functioning cities, then, are always a movement with and simultaneously against time. The forward motion ultimately becomes a flight into cyclical time, and cities eventually turn into temporally “fractured” zones where future and past coexist side by side.

Perhaps the “Backrooms architecture” of modern Western cities also emerged because this loop fell out of balance. Schattenmacher, in his videos on modern architecture, describes how architecture has lost any clear goal and has become a Trotskyist “permanent revolution” pursued for its own sake. This recalls the “lost future” Mark Fisher discussed in the previous essay.

Interestingly, Nick Land brings the Austrian theory of time preference into his theory of urban growth and its cyclicality, arguing that the city is a time machine and a means of resisting the flow of time precisely because it aims to halt man’s preference for the present. The city is supposed to encourage people not only to think of the present but to make long-term plans for the future. And Fisher, of course, claimed that the West has forgotten the idea of the future and now only seeks to preserve the present. In the literal sense, then, the West is dominated by present preference.

And according to Hans-Hermann Hoppe, tradition exists to suppress present preference and enable long-term planning. The temporal axis of the past and the axis of the future are thus interconnected. Severing one’s roots results in the loss of the future. There is no longer a “where from” or a “where to.”

The term used for the Backrooms is “liminal,” which means transitional. It is often explained by saying that a hotel corridor becomes liminal when you remove both the entrance and the hotel room — when there is only pure movement left but no destination. (And most versions of the Backrooms story include the element of lurking demons. One can never find an exit from the Backrooms, but one also cannot simply stop moving, or one will fall prey to these demons. Thus, one must remain part of a fundamentally meaningless movement.)

Mark Fisher also said that the loss of a future results in an ever-expanding bureaucracy and reforms pursued for their own sake — another manifestation of movement without direction.

But if this modern, colorless architecture leads directly to the liminal “Backrooms” effect of movement for its own sake, does that not also mean the guiding principle of “form follows function” ends up undermining itself? That the end product of “form follows function” is a system or object that is meaningless — whose function is to pretend it has a purpose, when in fact it does not?

After all, in the West there is already the phenomenon of “bullshit jobs” in administration and elsewhere, where people are hired into essentially useless roles that mostly hinder workflows.

Form follows function is not taken as seriously as it is preached.

From my own experience, it should be said that “form follows function” is a phrase especially popular among blowhards trying to sound important. But in reality, it is rarely practiced as rigorously as it is proclaimed.

An example: the previously mentioned company Apple is always associated with this slogan. But are they really as purely rational and functional as they claim to be? No. In the Frutiger Aero era, Apple was known for using lots of glossy effects and nature images. And many of their decisions make less rational sense than one might think.

For example, Apple integrates the computer into the monitor. But the monitor is usually one of the bulkiest and heaviest parts of a computer. Commodore, by contrast, integrated its computer into the keyboard, allowing users to connect to any screen or TV they could find. Strictly speaking, Commodore’s decision was far more rational than Apple’s.

And Microsoft’s decision to house all components in a “tower” that users could easily access to swap out parts — rather than buying a whole new machine every time — was clearly a “form follows function” move. Probably that is why Microsoft’s devices were derided as “ugly gray boxes only used for work” — because they were oriented towards function and labor rather than fun.

And would not the quintessential example of functional design be a Bitcoin miner — a massive rack of GPUs with cooling systems?

Even many famous Bauhaus designs, like the renowned Wassily Chair (incidentally, it is named after Wassily Kandinsky, who was also involved with the Bauhaus and whose paintings are clearly not examples of reason as a guiding principle.), were not purely based on functional logic. The steel-frame chair is more about aesthetics than utility. Bauhaus also collaborated closely with the Dutch De Stijl movement. Their iconic Mondrian Chair looks visually striking, but hardly seems comfortable to sit on.

It is also worth noting that Bauhaus founders like Walter Gropius actually wanted to break dogmas and promote free-spirited creativity. It is ironic that, after Bauhaus, especially in German design schools, the Bauhaus principles became rigid dogma. When figures like Antoni Gaudí or the Memphis Group broke with those principles in the 1980s, it was treated as scandalous.

It is likely that this new dogmatism — and the blowhards who overemphasize minimalism and functionalism — are partly to blame for the current state of things. The problem is not that people hold to these principles but that the mainstream exaggerates them. As Aristotle already observed, good intentions, taken too far, can become poison. And when today’s designers and architects seem totally blind to the fact that a large portion of their clientele openly complains about the ugly garbage they are producing, it becomes clear that something has gone wrong.

In some cases, the supposedly “functional” architecture promoted by Bauhaus and related architects has proven less functional than traditional methods. (A flat-roofed design, touted as more “functional,” ended up leaking rainwater into a house, and the owner wanted to sue the architects multiple times.) This ties in with Sigmund Freud’s idea that people usually desire things for irrational reasons and then invent rational justifications and excuses afterward. According to that logic, “form follows function” is a lie in most cases anyway.

Postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard also argued that, in postmodernity, every piece of furniture becomes more mobile, interchangeable, and multifunctional. It is no longer about the one function. This is linked to the breakdown of traditional family structures. In a modern house, there are no longer rooms for the father or the mother (or both), but instead, spontaneity dominates. There is no longer a “place of honor” at the dinner table for the “father of the house” — everything can be moved and rearranged.

This means that “form follows function” actually makes architecture even more interchangeable in postmodernity, because function becomes more fluid. People no longer have a fixed place in the system — they can be anywhere and nowhere. But in this way, they are also subjected to a kind of egalitarianism. If everyone can use every object equally, then symbolically, according to Baudrillard, everyone is placed on the same level.

Baudrillard’s analysis raises an interesting question: if, in functionalism, a room or object can no longer be identified with its “inhabitant” or “owner,” then that inhabitant or owner can more easily be removed or disappear. One no longer feels much of a sense of loss when a space becomes empty. In modernity, people no longer really have a “home.” They live in a “home” where they are, symbolically, irrelevant.

Baudrillard also makes another argument about functionalism: what would happen if a customer bought a product that perfectly fulfilled all his current needs? He would be satisfied — but would not buy anything else until the product was damaged. That is why, in Baudrillard’s view, products today can never be completely “functional.” They must always be a compromise — functional enough that the customer is satisfied and does not return it but flawed enough that the customer is willing to buy an upgrade.

The Brutality of Modern Architecture: Brutalist Architecture

One final major topic in the discussion of Bauhaus is Le Corbusier and his invention of Brutalist architecture. First off, the term Brutalism comes from the French word brut, meaning raw concrete — and is not originally meant in the sense of violence. Technically. But many critics of Brutalism argue that this term actually describes the impact of the style quite well.

While most Bauhaus designs tended to blend in subtly and seamlessly, Brutalism can be seen as a manifestation of modernity as the “pinnacle of a culture of dominance,” as Terence McKenna once described it.

And Le Corbusier, in terms of personality, was an almost perfect poster child for the effect of this kind of architecture. In his Voisin Plan, he demanded the right to tear down Paris and rebuild it entirely. In his vision of a new Paris, people would be crammed into massive skyscrapers serving as residential complexes. It is not far from Klaus Schwab and his Great Reset. Just consider the plans for so-called smart cities under the Great Reset, which would require demolishing existing housing stock. It must be said, however, that Le Corbusier was not the first to come up with such a “megalomaniacal” plan. In the 19th century, an architect named Eugène Haussmann already had large sections of Paris demolished and “rationally” rebuilt. Such plans seem to be a general feature of modernity and are the architectural counterpart to schemes like the creation of the “new socialist man.

Interestingly, Le Corbusier was also the only architect in the Bauhaus milieu who had almost no major conflict with the Nazi regime. Which, of course, fits with Brutalism as an architecture of dominance. Ironically, neoclassical architect Albert Speer — famously Hitler’s favorite architect — shared some parallels with Brutalism in his fondness for concrete and monumental aesthetics.

That said, many Brutalist buildings that were constructed were far from the standardized, uniform monotony of today. There were some truly outstanding works. Mark Fisher even counts Brutalism as part of the “lost future.” (Interestingly, Starfleet Headquarters in the Star Trek films is also a Brutalist structure.)

The typical Brutalist monotony (think prefab housing blocks), which gave this architectural style its bad reputation, emerged only later — after World War Two — when Brutalism came to be seen as a tool to provide cheap housing for the socially disadvantaged. (In the Soviet Union, these were known as Khrushchyovkas, named after Nikita Khrushchev.) This relied on cost-cutting through high standardization of components and very uniform construction. Many parts could thus be prefabricated and assembled quickly on-site.

It becomes clear, then, that it was only with the onset of standardization, massification, and the Guénonian “reign of quantity” that Brutalism truly became an architectural “sin.”

The YouTuber Europos described how, in post-Brutalist architecture theory, the raw concrete of Brutalism was replaced by the naked glass facades of skyscrapers. This is essentially a return to the liberal Bauhaus style as a symbol of the “open society.” But these facades are disorienting and deadly not only for humans but also for birds and other flying creatures. He finds this a symbolically rich aspect of modern architecture, describing it as something that seeks to rise to the heavens but stands in outright warfare with the heavens and its inhabitants. He describes this new “Tower of Babel” as a form of symbolic Satanism in modernity.

Symbolically, man is trying to build something that reaches the sky, to overthrow and kill its true inhabitants, and to take their place.

From Asia, there are many images of brutalist buildings whose bare, minimalist walls were used by residents to install technical systems like wiring and air conditioning units — sometimes resulting in 300 to 400 air conditioners hanging on a single wall. Cyberpunk films often borrow from such imagery, likely because it so aptly expresses Nick Land’s vision of the modern megacity as a “technical-cybernetic carcinoma.”

In a way, this is a distorted return of ornamentation. Human desire for decoration and embellishment has retreated, and the cybernetic system has moved in to claim the liberated space with its own kind of ornament.

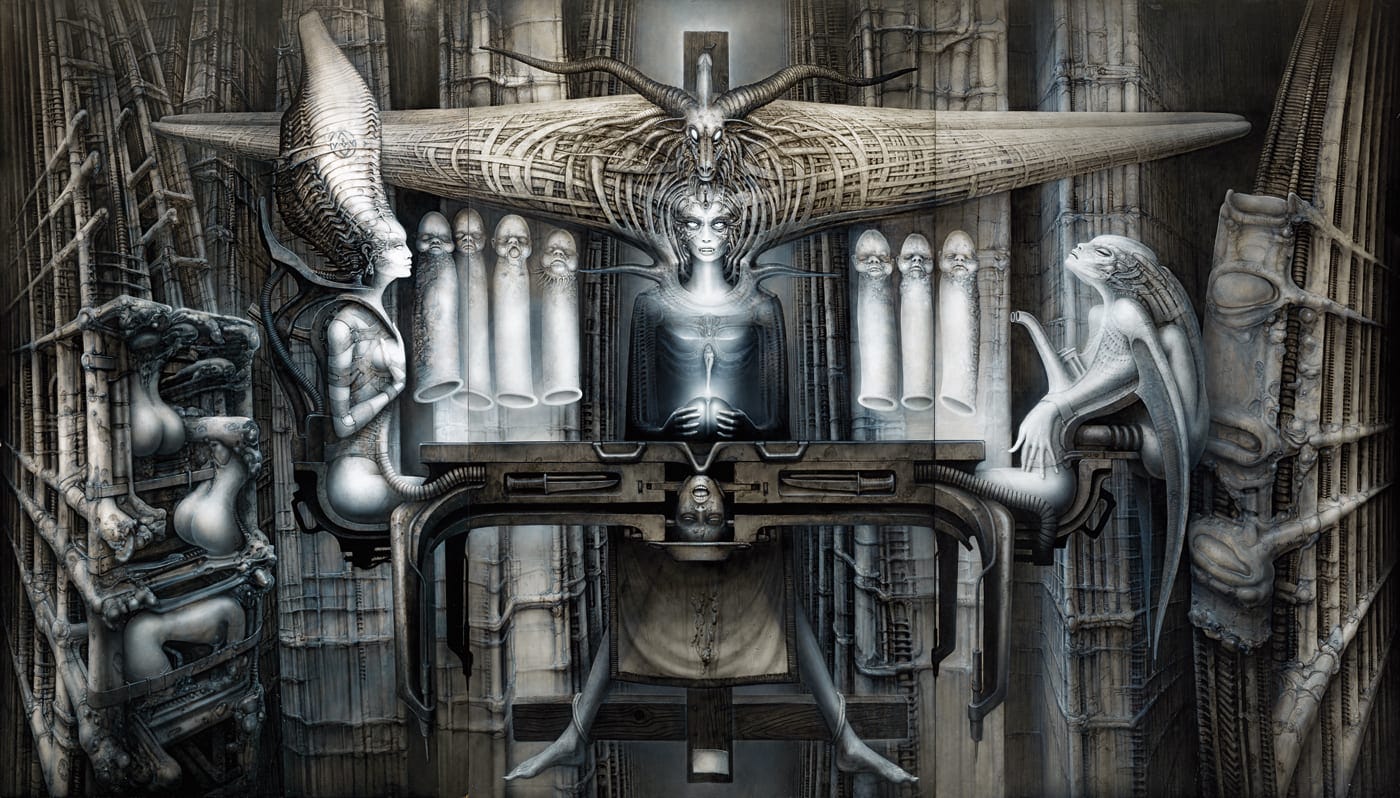

In conclusion, these images of technology absorbing and overgrowing the organic, like a disease, recall the work of another modern artist: the surrealist H. R. Giger. He painted technology as an amorphous, chaotic, dark (and demonic) mass that overwhelms all life, including humans — consuming and, quite literally, violating it.

Giger’s horror art — which inspired films like Dune, Alien, Urotsukidōji, Wicked City, and games like Metroid, Doom, R-Type, and Resident Evil — may well represent the true endpoint of what the Gestell (the enframing structure of modern technology) and the idea of “form follows function” really mean. Giger gives us a glimpse, in the present, of the future machine demon envisioned by Land (one might also call it Roko’s Basilisk) — the very being that modernity is seeking to awaken.

(Translated from the German)

This is a great piece. The picture at the top of the page is recognizable to anyone who has lived in Boston; it is the courthouse at government center, seen from beneath. Older Bostonians still lament the loss of Scollay Square, which was bulldozed to make way for this brutalist monument.

Another thing worth noting as a companion to these thoughts: one of the great French critics of architectural modernism is Jacques Tati, whose "Playtime" takes up many of the exact same observations of this essay, albeit in clever visual form. The fenced-in cubic house pictured in the middle of Part 1 is a dead ringer for the abode at the center of "Mon Oncle."