Esotericism and Bauhaus Architecture: Part 1

by Michael Kumpmann

Michael Kumpmann, reflecting on the recent German parliamentary debates about the Bauhaus and the AfD-triggered controversy, delves into the movement’s complex legacy — examining its ties to modernist architecture, craftsmanship, esotericism, and even Freemasonry — while critiquing its core tenet of “form follows function” as emblematic of modernity’s materialist reductionism, contrasting it with both traditional aesthetics and alternative architectural philosophies such as Anthroposophy, Zen minimalism, and Scandinavian design.

The recent discussions about the Bauhaus in the German parliament, and the scandal triggered by the AfD faction, have reignited an age-old debate. The magazine Krautzone immediately weighed in, posting a video suggesting that the Bauhaus should be abolished altogether because it looks terrible. The Left, on the other hand, interpreted the AfD’s rejection of the Bauhaus as a continuation of Nazi policies, which harshly opposed and shut down the Bauhaus as “degenerate art.”

The Bauhaus debate is complex because, on one hand, the Bauhaus can almost be seen as synonymous with modern architecture itself. Nevertheless, there are also some interesting aspects to learn from it, and a closer examination reveals anti-modern elements as well.

The pedagogical concept of the Bauhaus as a school was already fascinating and tied into the European tradition, stretching from ancient Greece, through the Renaissance ideal of the homo universalis, to Humboldt’s theory of general education, and even to Robert Heinlein’s educational theories (“specialization is for insects; humans must explore a wide range of skills”). The goal was to comprehensively teach students as many artistic techniques and genres as possible, enabling them to combine these techniques to create a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk).

The term Gesamtkunstwerk, which the Bauhaus used quite aggressively, also evokes the concept of the magnum opus in hermetic alchemy, which encompassed not only the life’s work but also the inner character development of the alchemist. (Interestingly, Humboldt’s concept of education also aimed in a similar direction, explicitly intending for the educated individual to become a more virtuous person through education.)

The Bauhaus described learned education as “building oneself,” which literally aligns with the meaning of the word “education” (Bildung) and conceptually traces back to the Christian mystic Meister Eckhart. Additionally, the Bauhaus sought to reconnect with the ancient tradition of craftsmanship, where there was no strict boundary between art and craft.

Some ideas of the Bauhaus (whose name alludes to medieval stonemasons’ lodges, Bauhütten) as a guild of architects and craftsmen, where external status or wealth should not matter and only skill and position within the guild should hold value, bear some resemblance to Freemasonry. There are no known individuals who were provably part of both the Bauhaus and Freemasonry. However, it is notable that Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius was well-versed in Freemasonic symbolism and actively used it in the Bauhaus Manifesto. Gropius even repeatedly referred to the Bauhaus as a “lodge,” a term that stands out in this context. The Bauhaus architect Lyonel Feininger, on the other hand, created a woodcut of a cathedral flooded with Freemasonic symbolism.

Regarding the connection between the Bauhaus and Freemasonry, it must be noted that the architect Antoni Gaudí, who was heavily criticized by Bauhaus architects, also used many Freemasonic symbols.

Some prominent members of the Bauhaus belonged to the so-called Mazdaznan, an offshoot of Zoroastrianism that also integrated theosophical concepts and ideas from yoga. This movement was explicitly Gnostic, declaring the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda as the ruler of the world of ideas and the Jewish god Yahweh as the lower Demiurge of the material plane. (Ironically, while the Nazis vilified the Bauhaus as a Jewish idea, many Bauhaus members considered Yahweh a kind of demon.)

There is also evidence that many Bauhaus members were interested in things like sex magick.

It is striking that these esoteric backgrounds somewhat resemble Rudolf Steiner and his Anthroposophy. However, Anthroposophists taught an architectural doctrine that was the stark opposite of the Bauhaus and its functionalism and, apart from a few niches, never gained widespread acceptance. The most successful Anthroposophical architect was Antoni Gaudí, and in the 1990s, there was a trend, represented by Luigi Colani and others, to use rounded forms in design, known as “blobject.” Both were influenced by Anthroposophy, but the latter faded away, and Gaudí remained an absolute niche phenomenon. Anthroposophists advocated closeness to nature over technology (even to the point of integrating trees into buildings or dedicating entire floors to trees), rounded forms, avoidance of right angles, use of vibrant colors, etc., making their architecture very “non-functional.”

While Steiner’s Anthroposophical architecture often had a strong religious connection (and some projects, like the Böttcherstraße, involved collaboration with religious scholars like Herman Wirth), the Bauhaus people almost always kept religion at arm’s length. (In a way, the pursuit of making functionality the standard for all things is, in the literal sense, a turn of architecture and art toward the profane. After all, the “everyday and non-religious” side of life is precisely what the word “profane” truly describes.)

Form Follows Function

Now, more specifically, to the Bauhaus’s most famous phrase: “Form follows function.” The form follows the function, implying that one should focus only on what is functionally necessary and avoid unnecessary elements.

This phrase is the primary criticism of the Bauhaus from the right. And from the perspective of the Fourth Political Theory, it must be said, rightly so. For modernity, whether defined by Guénon, Heidegger, Adorno, or others, is always, at its core, the reduction of everything to technical functionality and materialism. Thus, the Bauhaus is visually the epitome of modernity.

This is also connected to the fact that the principle of functionality was intended to simplify industrial mass production. As Ernst Jünger noted, the industrial worker is the central figure of modernity. The Iranian philosopher Ahmad Fardid saw the work of a craftsman as a direct expression of their existence, while uniform industrial labor is pure Gestell (enframing) and erases all traces of the existence of the workers involved.

Here, however, a small objection must be raised, as the Bauhaus, in part, sought to counteract this effect by incorporating more elements of craftsmanship into industrial production. This is why Bauhaus students were required to spend several months learning traditional craft skills.

It must also be said that the “Form follows function” principle was not invented by the Bauhaus; there were predecessors like the Austrian architect Adolf Loos with his book Ornament and Crime. (Adolf Loos, by the way, detested the Bauhaus and vehemently resisted being lumped together with them. Loos believed that the Bauhaus was too extreme and that one should not completely erase tradition and the old but should carefully consider where functionality might be improved.)

That this principle of functionality is at the core of modernity can be quickly illustrated by examples from women’s fashion (such as the Gothic Lolita subculture mentioned in the last article), where modernity means the renunciation of ornamentation (ruffles, bows, etc.), while clothing that seeks a return to tradition brings back precisely these decorative elements.

The same principle applies to typefaces. Modern typefaces are uniformly thick (while “traditional” typefaces like Fraktur use varying thicknesses to simulate natural handwriting) and use elements like serifs (small lines at the ends of strokes). Modern typefaces no longer use such elements. (Ironically, there is a very modern typeface called OCR-A, which uses serifs and has a very “futuristic” look. However, it was largely rejected as a modern typeface and is mostly used when explicitly referencing themes like science or computers. For example, two media that still use this typeface are the German band Kraftwerk and the cartoon series Pinky and the Brain.) In modernity, a minimally detailed typeface has prevailed. This goes so far that typefaces using serifs are now explicitly named to evoke ideas of antiquity and tradition, such as the typefaces Antiqua and Times New Roman. Modernity has even rejected the strikingly futuristic typefaces of the 1990s (now called “Y2K” typefaces) in favor of the simplest and least detailed typefaces.

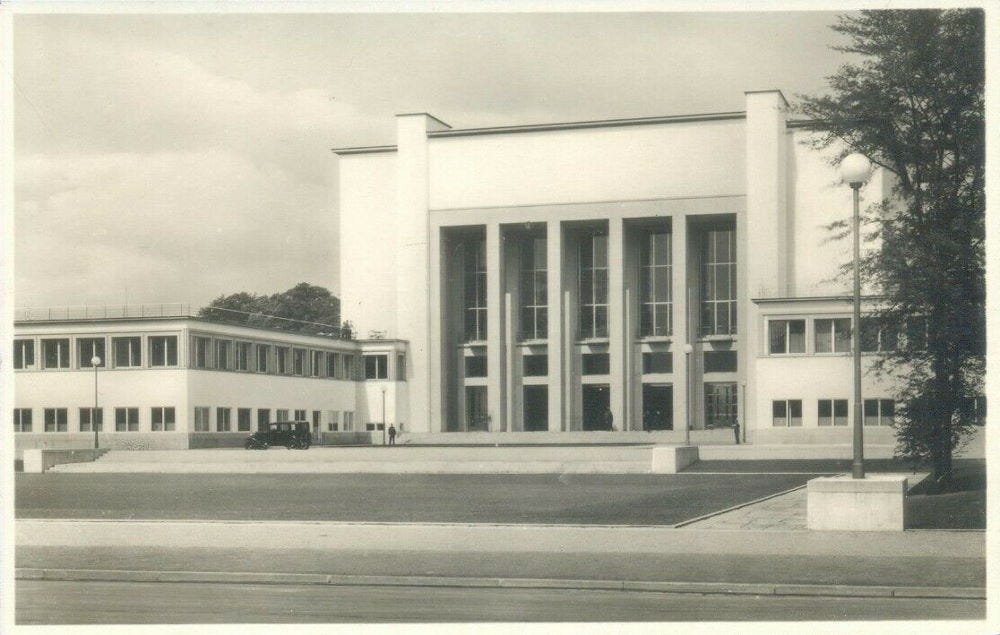

Regarding the “Form follows function” principle and technology, it must also be said that the Bauhaus, along with Italian Futurism, was one of the first design and art theories to embrace technology as an idea and explicitly wanted design objects to look technical. Earlier theories like Art Nouveau and its German counterpart, Jugendstil, attempted to hide technological advancements through natural forms and references to leaves, branches, or trees. Bauhaus design was explicitly meant to look technical.

On the other hand, the Bauhaus and its successors have a tendency to partially hide technology. This is particularly interesting when compared to science fiction, especially 1980s anime like Megazone 23. In this style (sometimes called “cassette futurism”), one tries to make things appear futuristic by deliberately emphasizing parts of the technology. In contrast, Bauhaus and other functionalist styles tend to hide everything from the user that does not directly contribute to input or altering the user experience. This can partly be explained by the rejection of ornamentation, as such deliberately displayed technology (in the special effects field for films like Star Wars, also called “greebles”) often becomes a form of ornamentation itself. And modernity, architecturally, is a hatred of ornamentation.

A phenomenon related to “Form follows function” that many people complain about is the “death of detail.” In the design of graphics like logos, details are increasingly being stripped away, leading to over-simplification.

Something often associated with the Bauhaus and the “Form follows function” dogma is the so-called “de-stuccoing.” Between the 1920s and 1970s, decorative elements and ornamentation were removed from facades to create smooth exterior walls. However, this development is not specifically tied to the Bauhaus. Even the Third Political Theory, which rejected the Bauhaus as degenerate, promoted this de-stuccoing. (See Werner Lindner.)

As is well known, all political theories of modernity are, at their core, alternative expressions of the same modern essence. And the fact that “Form follows function” is found across multiple theories of modernity shows how central it is.

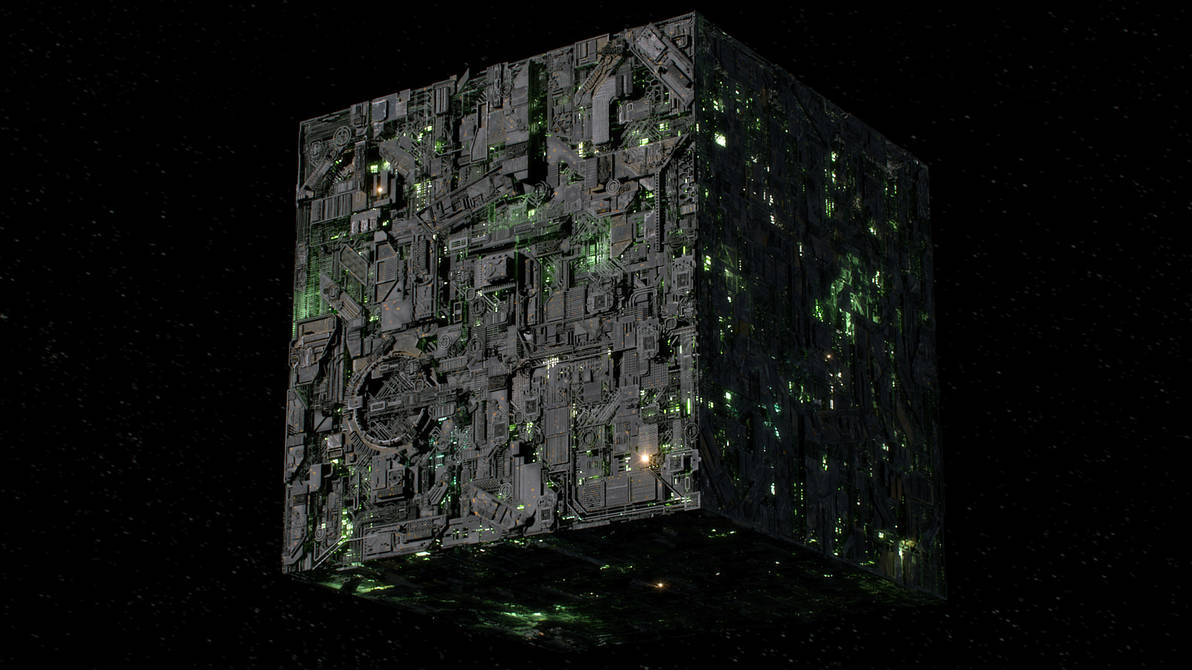

It is noticeable that there is now a trend to build new buildings entirely in the shape of cubes or rectangular prisms, as this is the most technically efficient form, providing the most storage space.

Here, it is ironic that cubes in the well-known sci-fi series Star Trek are associated with the Borg, a group of transhumanist machine beings who mentally enslave and bring other species under technological control through cyborgs, etc. Star Trek thus very explicitly depicted the “subconsciously resonating” aspect of modern architecture.

Architecture and Gender

Of course, it must be noted here that simplicity and minimalism do not necessarily have to be antitraditional or symbols of technological subjugation. Thomas Wangenheim pointed out in his YouTube video that, under certain circumstances, buildings with minimal detail and simplicity can also embody the solar masculine principle and are therefore used for official state buildings. An example is ancient Egypt, the oldest source of the European Western tradition. The most famous structures of this culture, besides the Sphinx, are the pyramids, which undoubtedly represent one of the simplest possible architectural forms.

Regarding the connection between official buildings and the solar masculine principle, Mark Passio provided the interesting example of the Place Charles de Gaulle in Paris, where Napoleon’s Arc de Triomphe was erected. The street layout forms a circle with rays extending in all cardinal directions, meaning the monument to Napoleon’s victories stands on a gigantic sun symbol. It is also interesting that this sun symbol was renamed in honor of the war hero, general, and later president Charles de Gaulle after World War Two. Notably, Charles de Gaulle did not want the triumphal arch to bear his name but rather the symbolic sun, the traditional symbol of masculinity.

Many other squares (such as St. Peter’s Square in the Vatican or the square in front of the Capitol in Washington) are also adorned with obelisks, which in Egypt symbolize the phallus of Osiris. (Interestingly, Disney’s Tomorrowland, which can be seen as a “lost future” in the Mark Fisher sense, features a giant rocket at its central plaza, which can be interpreted similarly in terms of form.)

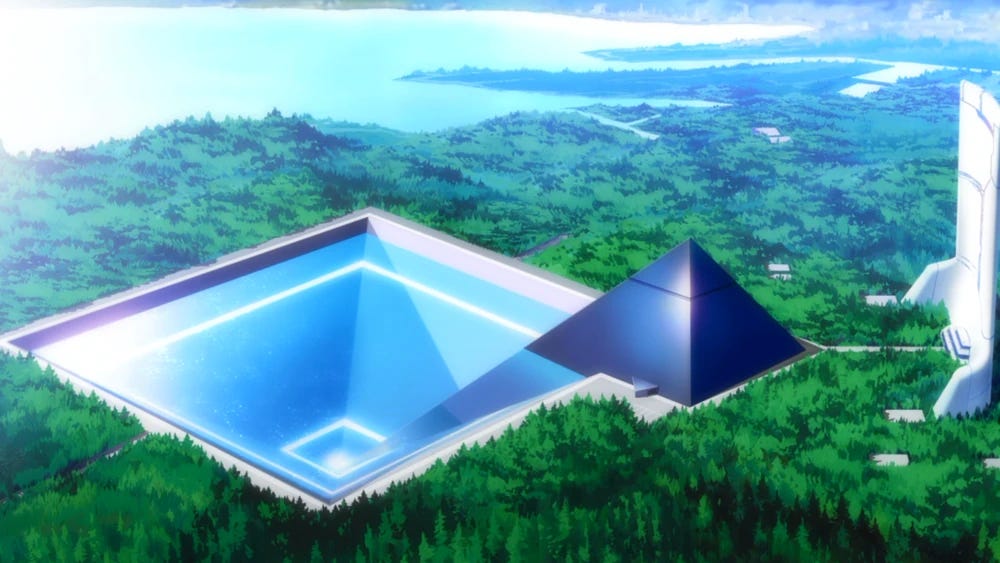

In science fiction, it is striking that many famous futuristic cities also use pyramids, which are “solar” in connotation. For example, the headquarters of the de facto ruling Tyrell Corporation in Blade Runner is a pyramid. The Jedi Temple in Star Wars is also a massive pyramid that towers over several skyscrapers. The Jedi, being both monks and elite knights, combine the two traditional paths of the solar masculine principle. In Neon Genesis Evangelion, the military organization NERV is housed in a giant pyramid. Thus, science fiction often follows traditional urban design principles.

However, Thomas Wangenheim rightly notes that for other, less state-oriented buildings, there must also be less austere, lunar structures. Not everything can be assigned to the hypermasculine, as that would be inhuman. A balance of genders is necessary.

This gendered aesthetic can be found in the examples discussed here, but also, and especially, in right-wing internet aesthetics. A masculine right-wing internet aesthetic is Fashwave, which directly incorporates Greek monumental architecture and its statues.

The online right-wing tends to favor the tradwife/cottagecore theme for feminine aesthetics, which is less minimalist and closer to feminine virtues.

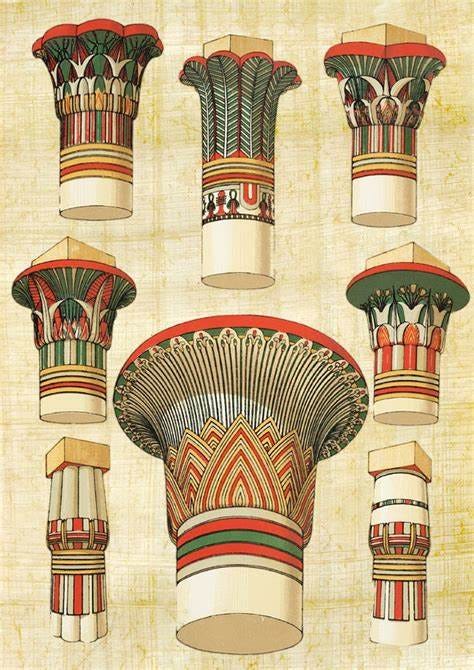

However, it must be said, as noted in Wangenheim’s video, that official buildings of the premodern era were rarely as austere as modern structures. (And even the cliché of white columns is not accurate, as historically they were brightly painted. The typical white appearance arose from finding them in a weathered state where the paint had worn off.)

Thomas Wangenheim also made an interesting argument that architecture and fashion are very similar and share common roots. The simplest possible form of architecture is the tent, and a tent is not structurally very different from a piece of clothing. Even tents are adorned with decorative elements.

Following this logic, the static elements like poles (the function) are comparable to the human body, and the decorative elements like fabrics (the form) are comparable to clothing. The pursuit of pure functionality is therefore a removal of clothing and an exhibitionist tendency. (Incidentally, many Bauhaus members were indeed active in the early nudist/naturist movement. Thus, the idea of exhibitionism as a tendency behind this architecture might be more accurate than one might initially think.)

Regarding the debate about simplicity and the abolition of ornamentation as architectural nudity, it must also be said that, according to Julius Evola, clothing — especially opulent clothing — is a way for humans to symbolically separate themselves from the realm of matter and ascend to the divine sphere. Therefore, exhibitionist nudity can represent a return of humans to matter. Conversely, leftists like Jean-Paul Sartre described certain forms of displaying nudity as a form of “objectification,” which points in a similar direction.

Thus, modern functional architecture can be seen as a worship of matter and an attempt to degrade humanity.

Arnold Gehlen, on the other hand, described clothing as a substitute for human fur. The most noticeable remnant of human fur is the hair on our heads. Among the Germanic tribes, it was customary to forcibly shave the heads of slaves. In England, it was at times forbidden for members of the lower class to have long hair. And in the Old Testament, there is the story of the giant Samson, who could be significantly weakened by cutting his hair.

This aspect of weakening and subjugating a person by removing their hair could symbolically play a role here through the logical chain of “clothing as a substitute for body hair and ornamentation as an extension of clothing.”

Additionally, across the world, there was the intentionally humiliating punishment of publicly shaving women’s heads. This again fits into the aspect of degradation.

Minimalism, Monasticism, and Zen Buddhism

What is always mentioned in discussions about minimalism is the Japanese tradition (Zen Buddhism, etc.). To some extent, this is valid. For one, the Japanese almost invented the idea of “white space” in design. White space means creating aesthetics by deliberately leaving areas empty. Therefore, Japanese aesthetics already present a strong contrast to some European ideas like the Baroque, which can be understood as a “showy aesthetic” aimed at displaying luxury.

This stems from Japanese philosophy and the idea of absolute nothingness (sunyata), as described, for example, by the Kyoto School. Roughly speaking, there is relative nothingness, which means the absence of something, where it is clear what should be there. Absolute nothingness, however, is nothingness in itself, which cannot be explained by the lack of something concrete. People often fear nothingness (Heidegger’s existential anxiety is explained in the Kyoto School through sunyata), but everything that exists and the way it exists is a reaction to this absolute nothingness. As the Heart Sutra states: “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.”

At the same time, this is an aesthetic shaped by monasticism, which seeks to renounce luxury. (There is also the aesthetic principle of wabi-sabi, which states that “minor flaws and signs of wear” can make an object more beautiful. This actually runs counter to the modern pursuit of technical perfection.) True to Buddhism, it is taught that too much distraction from unnecessary things confuses the mind, and therefore, less is more.

However, it must be said that this never went as far as modern Western Bauhaus minimalism and that Buddhist monasteries in Japan are often quite elaborately decorated. Additionally, a striking contrast between bright white tones and a very “vivid” red is frequently employed.

Japanese minimalism is also deeply connected to nature and seeks to dissolve the separation between humans, civilization, and nature. (For example, monasteries are often surrounded by lush gardens designed in such a way that they appear as little man-made as possible.) This minimalism serves to amplify the presence of nature by consciously restraining human-made elements. This stands in stark contrast to the barren Western Brutalism, which rather seeks to drive nature away.

Japanese architecture is also influenced by Taoism, which, in both architecture and landscape design, promotes the principles of Feng Shui. A core tenet of this philosophy is that humans should interfere with nature as little as possible, and if they do intervene, they must compensate for these intrusions with countermeasures to maintain balance. This constitutes a second foundation of the idea that human-made elements should be minimized so that nature can “shine” more prominently.

Another key element at play here is that Japanese Zen design often makes use of materials such as wood and stone, which already possess a natural structure and texture. Minimalism is then used to highlight this natural texture. Once again, the underlying principle is: less human intervention, more nature.

Interestingly, this element is also reflected in the so-called “Frutiger Aero” style, a “lost future” aesthetic that emerged with the iPhone and is therefore also referred to as “iPod Futurism.” While this style embraced a high degree of minimalism, it also featured strong natural influences, such as close-up images of wet grass or graphic ornaments of branches with cherry blossoms that subtly resemble Ikebana arrangements. It is worth noting here that Steve Jobs himself was a Buddhist, and his design principles were heavily influenced by Buddhist and, in particular, Zen ideas.

Aside from Zen, another frequently mentioned influence on minimalism is Scandinavian design. However, it must be noted that this is a modern aesthetic and, in essence, a derivative of Bauhaus. One aspect of this style that is indeed traditional and relates to space is its strong focus on light management and light conservation. In northern regions such as Scandinavia, daylight lasts extremely long in the summer, while winters are marked by prolonged darkness. Hermann Wirth thus interpreted the biblical phrase that “in paradise, a year is like a day” as referring to the Nordic countries, particularly the Arctic, where winter and summer are equivalent to night and day.

For this reason, Scandinavian design predominantly employs smooth surfaces and bright colors, as these reflect a portion of the light, resulting in better illumination. However, this aesthetic also incorporates the concept of hygge, which emphasizes coziness and livability, rather than purely focusing on functionalism.

The “Americanized” form of Bauhaus, known as mid-century modern, has a particularly interesting characteristic: there is a very fluid transition between the functionalist mid-century modern style and the deliberately futuristic Googie sci-fi architecture. (For example, Eero Saarinen’s Tulip Chair, a plastic chair, was featured in the conference room of Kirk’s Enterprise, and many elements of Oscar Niemeyer’s work on Brazil’s capital either resemble a Star Trek planet or were even directly adopted for some planetary designs in the series.) However, what is notable here is that the more “expressive” Googie style and the more functionalist mid-century modern style balanced each other out, leading to a more harmonious whole — without either one exceeding its limits.

To be continued…

(Translated from the German)

Nel ventennio fascista in Italia ci fu l'architettura della ricostruzione come Tresigallo, Latina, Sabaudia, Valdagno e tante altre. Architettura che riprendeva il classicismo ma nel contempo proiettata verso il futuro.