Donald Trump and the Rediscovery of Roots and the Future

by Michael Kumpmann

Michael Kumpmann discusses the tension between modernity’s abandonment of visionary futures and the efforts to reclaim them, examining how Archeofuturism, Esoteric Trumpism, and figures like Elon Musk, along with cultural movements like Japan’s Gothic Lolita fashion and intellectual frameworks like the Fourth Political Theory, aim to bridge the gap between tradition and futurism.

During his election campaign, Donald Trump spoke of bringing us “flying cars” and futuristic “freedom cities.” At first glance, this sounds utterly ridiculous — Trump as a president bringing to life the “silly TV science fiction” of The Jetsons or Futurama.

However, this might be far less ridiculous than it initially appears. The author Constantin von Hofmeister describes Trump in his book Esoteric Trumpism as an idealistic president who seeks to restore America’s dreams of the future and to save what the author Mark Fisher calls the “lost future.” Some of the more outlandish theories from the QAnon movement about Trump’s Space Force, Solar Warden, and his influence on alien wars suggest that certain factions of Trump’s supporters literally view him as a real-life Captain Kirk.

Popper’s Abolition of the Future

But what exactly is this “lost future”? The postmodern author Mark Fisher proposes in his book Capitalist Realism the thesis of an invisible but all-encompassing meta-ideology he called capitalist realism. This ideology broadly claims, much like Karl Popper argued in The Open Society and Its Enemies, that modern liberalism is the only viable political ideology, and even entertaining the thought of an alternative leads straight to disaster. Instead of attempting to change the system, people are encouraged to pursue only minor reforms and incremental improvements. This micromanagement of bureaucracy has run rampant under postmodern neoliberalism.

Fisher argues that this core assumption is deeply entrenched in society. Consequently, today’s Western left is a group of total failures. They speak of the necessity to abolish capitalism and establish communism, but such demands are either youthful daydreams or mere “bar talk.” When the left gains power, they abandon these plans immediately in favor of left-liberal micromanagement or a continuation of the status quo. Due to the rejection of any alternative, major changes in Western politics never occur. (For instance, Barack Obama initially criticized George W. Bush for many policies, such as the wars in the Middle East, only to continue them once elected.)

One effect of this capitalist realism is that people’s temporal horizons shrink to the immediate present, and they lose the ability to conceive of long-term concepts of the future. It is worth noting here that this echoes Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s thesis of the extreme rise of present-time preference in liberal modernity. However, whereas Hoppe and Michael Anissimov attributed this to liberal democracy rather than capitalism, Fisher uses a different definition of capitalism. For Hoppe and Anissimov, capitalism equates to the free market. Fisher, on the other hand, argues that capitalism is both an ideology about markets and a system that politically favors certain market actors over others.

This means that the future disappears from thought, replaced by an endless present. The future is broken off. Over the past 24 years, we have experienced this phenomenon acutely.

In the 1950s, nuclear power symbolized a golden future. Plans were made for home reactors and nuclear-powered cars (the latter would have allowed the average person to refuel only once a year or even once every two years). Yet now, Germany’s Green Party has dismantled and destroyed its nuclear facilities with acid, opting instead to import LNG gas from the United States, which involves chemically contaminating parts of the North Sea.

The legendary Concorde was retired. The Space Shuttle program in the United States ended. Germany’s last great futurist project, the Transrapid, was abandoned after an accident that was clearly caused by human error. When George W. Bush suggested building a space colony, he was laughed at.

Instead of an optimistic future, the West is inundated with dystopian scenarios like the climate apocalypse.

This leads to the paradoxical situation where people watch new Star Trek films set 300 years in the future to feel nostalgic for a past that is now over 50 years old. The future is dismissed as a ridiculous fantasy, yet the spirit of unfulfilled future dreams haunts people like a guilty conscience or a literal ghost.

Julius Evola spoke of the Westerner as a “man among the ruins,” standing among the remnants of his great past. Today, however, a second, equally large pile of debris has formed in the Western psyche: the ruins of countless unfulfilled promises of the future. Westerners have no roots, no future, but they have billions of genders to choose from.

For the United States in particular, the abolition of the future and the end of the “Faustian man” are especially significant because they mark the loss of something integral to the American identity. As I argued in a previous text based on Alexander Dugin’s analyses, the American nomos and existence are tied to the idea of the frontier. This is not merely the uncharted territories of the Wild West. By the 1950s, it had come to symbolize the belief that utopian visions of the future were literally just around the corner, waiting to be discovered.

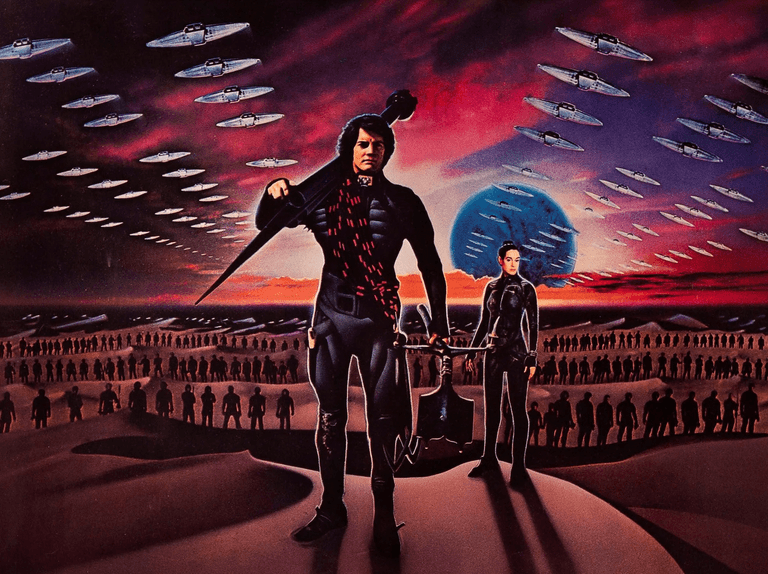

Constantin von Hofmeister speculates in his book that the Trump administration — and particularly Trump’s supporters — seek to escape this intellectual impotence of the West. Trump, therefore, is envisioned as “Archeofuturist,” capable of rescuing both the past and the future. In the end, he might unify the two, giving equal regard to tradition and futurism — similar to science-fiction works like Frank Herbert’s Dune or Legend of the Galactic Heroes.

China’s Path Towards Tradition and the Future

China may already be evolving in precisely this direction. (Much like Japan in the 1980s, before it was hit by an economic crisis, a lost decade, and a spiritual malaise.) China is increasingly developing into a Confucian revivalist state, while simultaneously embracing its role as a futuristic high-tech nation. As the West abandoned projects like the Transrapid, China is currently constructing several lines of its monorail system. China might be the best example of why tradition is needed to save the future.

Within Trump’s cabinet, one individual who most strongly embodies the rescue of the lost future is the libertarian Elon Musk. Through his companies, Musk is working on projects like the Hyperloop (a magnetic levitation train), space colonies, and more — striving to make the lost future a reality.

Elon Musk, Silicon Valley, and the Californian Ideology

Elon Musk comes from Silicon Valley, which for years was known as a hub of futurism and libertarianism. Just a decade ago, Apple’s grand presentations of new devices and technologies generated immense excitement for innovation among the general public. (The structuralist Umberto Eco even described companies like Apple as having a symbolic religious character. This could, if generously interpreted, be called Archeofuturist.) Today, however, the West’s enthusiasm for technological novelties has waned. Most people barely noticed Meta’s augmented reality glasses, if they noticed them at all. The emergence of AI also passed with little fanfare or advance promotion — it was simply suddenly there.

Elon Musk represents the last vestiges of the old Silicon Valley spirit. But what does that mean? What is the Californian ideology?

The founder of the “Silicon Valley ideology” was essentially the ex-hippie Stewart Brand, a libertarian heavily influenced by Robert Heinlein. In the 1960s, Brand pressured NASA to release its photos of the Earth as seen from space. Inspired by this, he published the Whole Earth Catalog in California, a magazine that Steve Jobs later described as “Google’s analog precursor.” This publication included tips for commune founders and young entrepreneurs, articles on the development of computer technology, neo-leftist philosophy, libertarian critiques of the state, and discussions on topics like cybernetics and futuristic utopias. The magazine served as a bridge between neo-leftists, hippies, computer scientists, and tech entrepreneurs.

Silicon Valley became a magnet for libertarians, many of whom would later become active in Donald Trump’s orbit. Consider figures like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and John Perry Barlow (who also wrote songs for the band The Grateful Dead). Even ex-hippie and Apple co-founder Steve Jobs (who initially sold apples on a California commune) was known for libertarian views, such as wanting to abolish the public school system in favor of state-funded vouchers for private schools. Libertarians, in turn, wrote books comparing famous tech entrepreneurs like Bill Gates to Ayn Rand’s character John Galt.

A fundamental idea of the “Californian ideology” is the vision of computers and the internet as tools capable of upending existing relationships and dismantling political systems. (This foreshadowed ideas like Nick Land’s accelerationism.) Notably, this vision explicitly entertained the idea that the hegemony of the U.S. and liberal democracy could be destroyed, and that this might even be positive — even if it also led to the strengthening of fascism or other forms of governance. Projects like Silk Road and cryptocurrencies, which are also used by countries like North Korea and Iran to circumvent sanctions, align with this ethos.

Big Tech’s Turn Away from Libertarianism

Today, Big Tech companies like Google are known not for championing freedom but for embodying censorship and manipulation infrastructures that eerily resemble the S3 Plan from the Metal Gear games. It is worth noting, however, that Silicon Valley has always had a darker side. Companies like Facebook and Google received massive support from U.S. intelligence agencies. Alex Jones was among the first to warn about Big Tech. Therefore, it must be said that the techno-libertarianism of Silicon Valley was deeply hypocritical.

In 2017, a memo by Google employee James Damore revealed that Google had been systematically shifted toward left-liberal ideology through Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives. Employees with dissenting opinions were systematically driven out through bullying, false accusations, and other intrigues. Ideologically aligned individuals used nepotism to bring like-minded people into the company, prioritizing ideological conformity over productivity and profit. Investigations by Breitbart revealed that similar practices occurred at other companies like Facebook. Pixar employees also used underhanded tactics to seize control of the company.

To combat this woke censorship, Elon Musk purchased Twitter (a move that also caused friction with the European Union). After the acquisition, Musk subjected the workforce to rigorous scrutiny to identify productive employees and dismiss those who had gained their positions through DEI, wokeness, and nepotism. Ultimately, he fired over 6,000 employees — more than 80% of the workforce. This illustrates a broader problem of Liberalism 2.0: the parasitic nature of bureaucratic management.

The Neoreactionary Influence on Silicon Valley

In the orbit of Silicon Valley is Mencius Moldbug (Curtis Yarvin), a personal friend of Peter Thiel and an intellectual influence on Vice President JD Vance. Moldbug is known for advocating the abolition of liberal democracy and a return to traditional feudalism, drawing on libertarian ideas (Hans-Hermann Hoppe) and thinkers like Carl Schmitt. Others, like Michael Anissimov, have linked Moldbug’s ideas to Julius Evola’s integral Traditionalism.

In Germany, I was among the first to write extensively about Moldbug and the Neoreactionary movement (Nr/X). Later, after my initial articles for Eigentümlich Frei, other authors from the magazine, such as Florian Müller, founded the journal Krautzone. This journal, the only neoreactionary magazine in the world, has (half-jokingly) committed itself to saving the Transrapid and, by extension, to rescuing the “lost future.”

How Should We Best Approach the Lost Future?

How should we assess the situation? Advocates of the Fourth Political Theory, who are often followers of Heidegger, tend to be critical of technology — and rightfully so. Considering the connection between Elon Musk and José Delgado, should we really follow a man who might bring us sci-fi technologies like monorails and household robots but simultaneously fund research that could transform humanity into a herd of uniform techno-zombies? Caution is warranted here.

Guillaume Faye’s concept of Archeofuturism sounded intriguing, but his book also contains extremely questionable ideas, such as the creation of genetically modified slave races.

On the other hand, Alexander Dugin recommends potentially dangerous technologies like nuclear power in his books for a future Eurasian empire. Yet Faye’s term “Archeofuturism” was a “marketing masterpiece” that inspires dreams and is easy to understand. Moreover, Elon Musk is emerging as Trump’s “best man,” which builds trust.

Perhaps we should approach this from a fundamentally Traditionalist perspective — emphasizing tradition rather than technological enthusiasm. Archeofuturism and technological ideas could be framed as expressions of tradition. For example, Steve Jobs was a practicing Buddhist who integrated Buddhist principles into Apple products. Jack Parsons, who contributed to NASA’s development, was a Thelemite, and Robert Heinlein was influenced by Thelema. Arthur Conan Doyle was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. H. P. Lovecraft was familiar with esotericism and came from a Freemason family. John Carter of Mars, like Alice in Wonderland, is essentially a theosophical story. The noble, wise race of the Arisians in the Lensman series references theosophical ideas, as is evident in their name. Star Trek expresses Posadism, the leftist counterpart to figures like Savitri Devi and Miguel Serrano. The Vulcans in Star Trek are essentially Taoists or Buddhists in space, akin to the Jedi in Star Wars. Dune is a story about Islamic civilization and the Mahdi. And so on.

Perhaps this could be an approach to dealing with such lost futures.

In some sense, proponents of the Fourth Political Theory are already working to salvage lost futures. According to Mark Fisher, this does not just involve sci-fi concepts but also ideologies like communism, which have been “lost.” The Fourth Political Theory collects useful aspects of peripheral elements from the three modern political theories — such as Traditionalism, Herman Wirth’s theories, elements of communism, and the Austrian school of economics. By doing so, we have long been reviving parts of political concepts that became lost futures, countering the liberal “end of history” in capitalist realism and enabling an alternative future.

A Task for the Fourth Political Theory: Reviving Lost Futures

One critical task for the Fourth Political Theory, particularly regarding design and aesthetics, is to analyze and identify commonalities in many lost futures and understand why modernity failed to develop in those directions. Often, this is surprisingly straightforward. When examining images of lost futures — whether from the West, North Korea, or Disney’s Tomorrowland — a fundamental contradiction with modernity becomes apparent.

According to René Guénon, the defining principle of modernity is the “reign of quantity.” This essentially means reducing everything to a small number of simple basic elements and endlessly repeating these to achieve maximum standardization. This explains why we do not live in buildings with round, flowing forms like those in Disney’s Tomorrowland parks but instead in ugly concrete cubes erected by modern architects everywhere. Modernity seeks inhuman standardization, sweeping away both traditional architecture and humanity’s dreams of a future like Star Trek’s Federation.

Learning from Lost Aesthetics

This critique could also extend to architects and designers who were defeated by dominant German technofunctionalism, epitomized by the “form follows function” ethos. Figures like Antonio Gaudí or the Memphis Group offer alternative visions that modernity sidelined. These alternative aesthetics might hold the key to reclaiming the dreams and ambitions of the lost future.

Functionalism is also a central aspect of modern fashion (partly influenced by designers like Coco Chanel and her “little black dress”). There are some youth cultures that vehemently oppose this concept of “form follows function” and, in doing so, revive traditional fashion. Take, for example, Japanese Gothic Lolita fashion, which is certainly worth a closer look.

(Translated from the German)

Following a linear pattern of Architecture Brutalism was the last significant style and is seemingly making a comeback. Astrology is the 'Archeo' because myth is persevered there. The 4th political theory means multi-polarity rather than uni-polarity however its thesis not only is far away from the mainstream , much due to lack of translations, but lacks a presence in academia for discussion and debate. I cannot say lets go with that concept without THAT type of discussion and analysis amongst my piers along with the other elements of water and air.

IDK-"capitalism" thrived under monarchs and dictators and better under auhoritarian regimes in the true sense.

Free Market never existed. Gov't always controlled economy to some extent except in its most outlandish form of local warlords doing whatever they wanted via money and force, the two faces of power.

Germany did not opt out of Russian LNG. U.S. sabotaged Nordstrem and Germany has been going broke ever since on American LNG.

Spengler and Evola both talked about endless frontiers and so did Heinlein IIRC but "Star Ship Trooper" is just WW2 sans "Hogan's Heroes": fun, but make the "bugs" humans and it's a tragedy.

Elon Musk Is child in Red PIll clothing. He's censored more on X than Dempsy ever did and his stance on H-1B visas are tyrannical in every bad sense i.e. keeping compay secrets. Peter Thiel is worse.

A 4th Political Theory is not of the past or any lost future but something we have not seen on Earth before the technology comprising economies of the world has never been seen before.

Here, I 'd agree with the essay and maybe Rechtenwald and Rerum Novarum.

The great economic theories are all locked in the technology or means of production of their day. Marx began to make sense when Adam Smith didn't any longer because machines had rendered the proletariat more important than capital and artisan work of Smith's day. That the bourgeosie identified with has-been aristocracy rather than the proletariat was Marx's gripe which an American today might better understand because out heute bourgeosie have become as much the snobs.

As global literacy and multi-polarity increases, the less we need "heroes".

We all just want a life.

“I came to realize that one single human being, comprehended in his depth, who gives generously from the treasures of his heart, bestows on us more riches than Caesar or Alexander could ever conquer. Here is our kingdom, the best of monarchies, the best republic. Here is our garden, our happiness.”

― Ernst Jünger, The Glass Bees