A Fatal Chain of Events: How the War Began

by Dominique Venner

Dominique Venner examines how the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand became the spark that ignited a powder keg of nationalist tensions, alliance obligations, and technocratic thinking that overwhelmed political wisdom across Europe.

Sarajevo, June 28, 1914. By what spell would the assassination in the Balkans of an unknown archduke precipitate Europe into war?

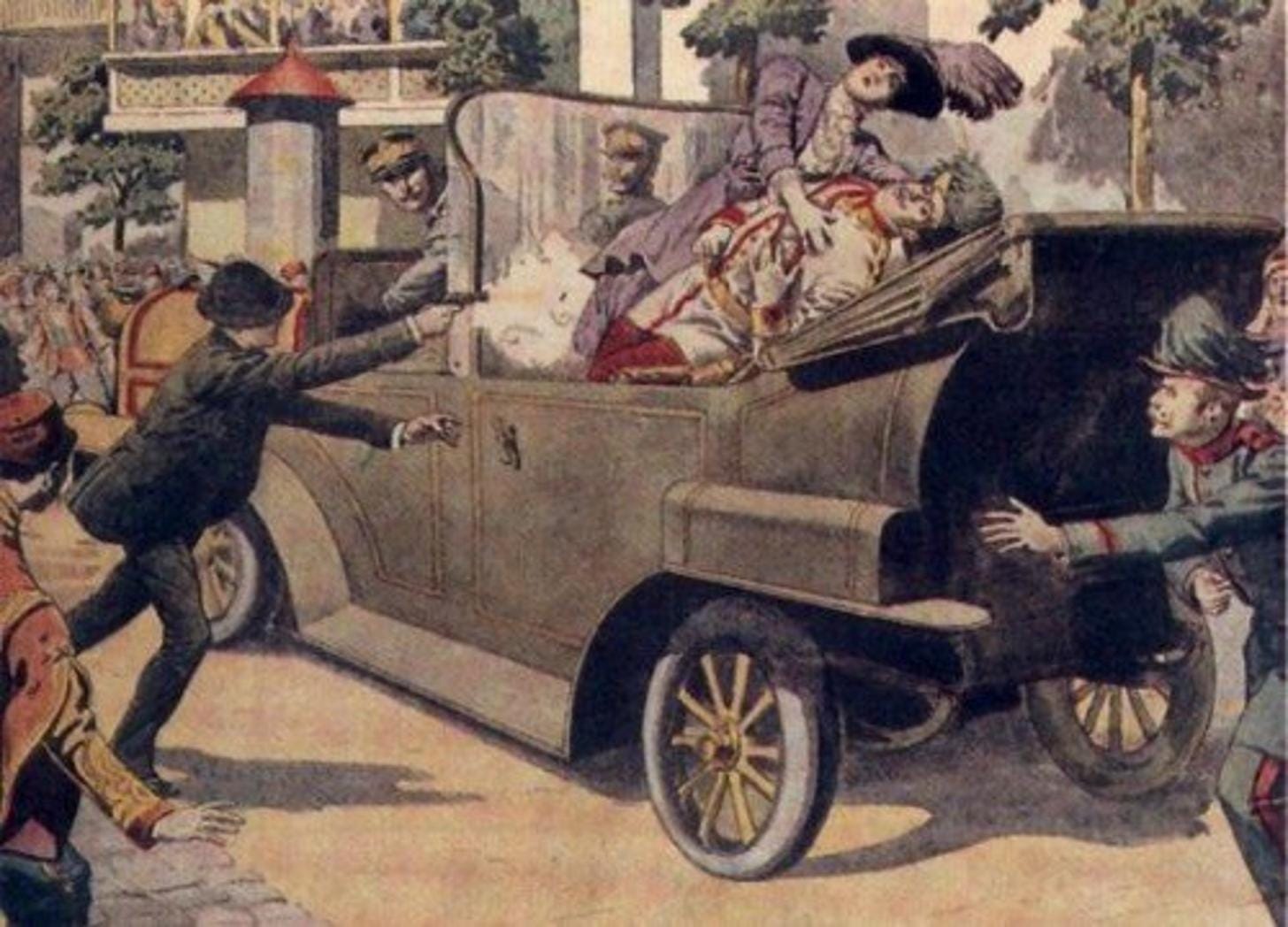

On June 28, 1914, the carefree Paris of the Belle Époque was not thinking about war at all. On the grass of Longchamp, the Grand Prix was being contested in the presence of an audience of elegant women. At the official tribune, ministers and diplomats smiled without constraint. Between the third and fourth race, an aide-de-camp delivered a message to President Poincaré. He was seen to turn pale. He handed the note to Count Szecsen, ambassador of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, addressing a few words to him. The diplomat seemed seized with vivid emotion. He hesitated for an instant, then left the tribune. The news spread immediately: the heir to the Habsburgs, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife had just been assassinated in Sarajevo!

A month later, the double gunshot of Sarajevo precipitated the world’s plunge into the most terrible war it had ever known: 9 million dead, suffering and upheavals of unimaginable magnitude. It triggered in a chain the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the advent of the USSR, the disappearance of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, of Imperial Germany, of the Ottoman Empire, and the complete dismemberment of Central Europe in 1918, the rise of Hitlerism in 1933, the Second World War in 1939, and the general upheaval of the universe. None of these events was written in the stars. The First World War was not a fatality. It required an exceptional combination of circumstances and the detonator of a chance attack, the most fascinating murder in history due to its disproportionate consequences.

In that beautiful summer of 1914, the fragile and complicated balance of Europe, the calculations of politicians, the combinations of chancelleries were swept away in a few moments by the plot of an obscure group of officers and adolescents from a distant Balkan country, who knew nothing of world politics, understood nothing about Europe, and wanted only one thing: to satisfy their hatred of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the main obstacle to their dream of a "Greater Serbia."

They were members of the Crna Ruka, the "Black Hand," a Serbian terrorist organization that claimed 120 assassinations over three years. The soul of the conspiracy was Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević, 37 years old in 1914. With his brutality and thick neck, he well deserved his nickname: Apis, the bull of ancient Egyptian beliefs. Eleven years earlier, he was among those who had taken an active part in the assassination of King Alexander I Obrenović and Queen Draga, too lukewarm toward Austria. In a token of recognition, the new king Peter I, of the rival Karađorđević dynasty, had promoted Apis to head of the intelligence services of the Serbian general staff.

After 1912, Apis's boiling energy had concentrated against Austria, in the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina claimed by Serbia. His faith in resorting to terror was vigorously encouraged by the Russian attaché in Belgrade, Captain Artamanov, who lavished subsidies and assurances:

"Have no fear," said the latter. "If your actions push Austria to war against Serbia, Russia will intervene."1

Since the beginning of 1914, Colonel Dimitrijević had been contemplating a great coup: assassinating the heir to the throne of the Habsburg Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The Austrian Empire, with its great past, had entered its decline, in the image of its emperor, Franz Joseph, then 84 years old. Trials seemed to have relentlessly pursued this dignified, austere sovereign with short views. Under his reign, which began in the blood of 1848, Austria had been cruelly defeated twice, by the Italians supported by France, then by the Prussians at Sadowa. In his own family, there was only a succession of dramas.

The respect that surrounded the old emperor, the weight of habits, and a benevolent authority had become insufficient to maintain the cohesion of the venerable empire, where hostile peoples confronted each other, inflamed by nationalist passions. The only man perhaps capable of changing the course of things was the heir to the throne, the emperor's nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Rough, energetic, endowed with political flair, at 51 he was at the height of his form. A great hunter, military as one was in the old nobility, he took his functions as Inspector General of the imperial army very seriously, and knew he was listened to by the officer corps, whatever their nationality.

Against the emperor's will, he had married for love a daughter of the minor Czech nobility, Countess Sophie Chotek.

The heir to the throne was the opposite of a liberal turning with the winds of fashion. He was an audacious spirit. A sort of revolutionary from above, in the manner of Stolypin or Bismarck. He was conscious of the perils and felt he had the strength to bring salutary reforms. The archduke did not hide his intention when he ascended the throne to associate the Slavic populations of the empire with a renovated monarchy, through reunion within an autonomous community of Slovenes, Croats, and Bosniaks. His goal was to reconcile the hostile nationalities in a modern federation. For the fanatics who dreamed of a great state of the South Slavs under their direction, the archduke was therefore the enemy.

The Vanguard of Pan-Slavism

In 1914, Serbia was one of those recent Balkan states, like Bulgaria, Romania, Greece, Albania, or Montenegro, subjected for centuries to Turkish domination. The Serbs, like the Bulgarians, Albanians, or Macedonians, had only freed themselves in 1878 to tear each other apart. In 1912, Serbs and Bulgarians had joyously slaughtered each other around Macedonia. The former had emerged victorious from this bloody confrontation, and their ambitions in the region knew few limits.

Encouraged by the Russians, they dreamed of reconstituting the Greater Serbia of the 14th century, a territory four times larger than the kingdom of 1914. A dangerous ambition. The coveted territories belonged almost all to a great power, notably the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Their reunion could therefore only be achieved following a general conflagration throughout the region.

Serbian propaganda was exercised particularly in the Austrian territory bordering Bosnia-Herzegovina, placed under Austrian authority since 1878, where it found a favorable echo in the Orthodox minority.

From 1912, several new facts had raised tensions. In Russia, the disappearance of Stolypin had ended the moderating influence that this great minister exercised in foreign policy.2 Beaten and humiliated in Manchuria in 1905, having lost its possibilities for expansion toward the Pacific, Russia then turned toward the Balkans, where it could count on the solidarity of the "South Slavs" to undermine the Ottoman Empire, reach the Straits, and emerge toward the Mediterranean and free seas.

Except Russia encountered two formidable rivals in the Balkans. Politically, the Austrian Empire; economically, the German Empire. In 1878, then in 1908, Russia had been forced to recognize Austrian sovereignty over the former Turkish territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But this had in no way cooled the ardor of the Pan-Slavist clan in Saint Petersburg, headed by the Tsar's uncle, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, designated commander-in-chief of the Russian army in case of war. A giant insensitive to nuances, a sort of satrap in the Moscow style, he was whipped up to white heat by his wife and sister-in-law, the Montenegrin princesses, fanatical Pan-Slavists, who had made him the brother-in-law of the King of Serbia.

"Russia intends to make Serbia, enlarged by the Balkan provinces of Austria and Hungary, the vanguard of Pan-Slavism," Russian diplomat Hartweg had explained to Filality, Minister of Romania, on November 12, 1912.

In Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia, as in Belgrade, it had been known for months that Archduke Franz Ferdinand was to attend, at the beginning of summer 1914, the great maneuvers of the Bosnia-Herzegovina troops in his capacity as inspector general of the imperial army.

It was there, in Sarajevo, on June 28, 1914, that, following a series of incredible chances, Franz Ferdinand and his wife would be assassinated by Gavrilo Princip, a young terrorist member of the Black Hand, barely 20 years old.3

The only man who could perhaps prevent the armed confrontation between Austria and Serbia had just died.

During the following weeks, the Austrian leaders seemed paralyzed. Yielding to confusion, they were incapable of analyzing the event and its consequences.

It would have required a superior spirit and exceptional energy to speak a language of reason and responsibility. But that spirit had just disappeared. Only the old emperor remained. At 84, worn down by misfortunes, bereavements, and disappointments, it was no longer his place to command events.

Fatalism was his ultimate refuge. He seemed to cling to a single thought: "If we must disappear, at least let it be with dignity."

But no more than in Austria, in none of the other great powers was there then a man with sufficient authority, courage, and clairvoyance to muzzle the blind forces and insane chains of events that would lead the world to war a month after the double murder in Sarajevo.

Russia Mobilizes

The Russian Foreign Minister, Sazonov, a fanatical Pan-Slavist, was unstable, of morbid hypersensitivity, readily yielding to the rhetoric of warlike mysticism. Austrian Prime Minister Berchtold was a frivolous spirit, a fop whose conceit could lead him to the worst extremes. In a situation that called for exceptional temperaments, the destiny of the two main antagonists was delivered to a neurotic and a scatterbrain who let themselves be pushed to war by opinions heated by the press, but also by vindictive and presumptuous general staffs.

Fate willed that in that summer of 1914, European statesmen of high stature were lacking. In Russia, Stolypin had been assassinated. In France, Caillaux had been sidelined by the murder of Calmette. In Germany, Chancellor Bethmann as well as Wilhelm II were hostile to war, but they had neither the intelligence to restrain Austria in time nor the strength to oppose the pressures of Moltke and the great general staff or those of public opinion. In Austria-Hungary, Count Tisza, Prime Minister of Hungary, a reasonable spirit and fundamentally hostile to war, could not make his views prevail and bowed before the blindness of Franz Joseph, in solidarity with Berchtold.

However, Austria initially had very strong assets. The odious assassination of Sarajevo had aroused the horror of all Europe. But the government of the dual monarchy let the opportunity pass to strike quickly and forcefully to obtain guarantees on Serbia's future policy, instead procrastinated and waited nearly a month to address a rather confused ultimatum to Serbia, giving its adversaries time to recover, turn opinion around, and prepare responses.

Facing them, the Russian leaders, except for the Tsar, were determined to use the Serbian pretext to destroy Austria, the main obstacle to their ambitions in the Balkans. These two powers would drag their respective allies, Germany, France, and England, through the automatism of alliances.

Germany of 1914, which suffered from its isolation and felt encircled, had only one sure ally, Austria-Hungary. It could not allow its existence to be threatened. It assured it of its unwavering support, but all the while tried to avoid a generalization of the conflict. The role of French leaders was no clearer. Poincaré certainly did not view without pleasure the hour of a long-awaited revenge against Germany. Like most other European leaders, he believed in a short war and, deluding himself about Russian military power, did not doubt that within a few weeks the Tsar's innumerable cavalry would water their horses in the waters of the Spree. The assurances and encouragement lavished on Russia during the fateful month of July 1914 weighed heavily in the outbreak of war through Russia's general mobilization on July 30, 1914.

It was this decision that lit the fuse. In the perspective of the time, mobilization was the real act of war. Declaration was only a subsidiary and outdated formality. The technical arguments invoked with fever by Moltke during the German Council of Ministers on July 31 were largely legitimate, which does not exonerate this officer from a bellicose attitude that contributed to reinforcing the military and Austrian leaders in their aggressive will against Serbia.

The German general staff watched in anguish. Its extremely complex strategic assembly system had been established based on the presumed dispositions of France in the West and Russia in the East that placed Germany in an iron and fire vice. If the Russians got ahead of Germany, the whole system could break down.

Fear of Encirclement

Forced to fight on two fronts between adversaries who together had crushing superiority, Germany found itself in the situation that Israel would later know. It could only defend itself by attacking. And it had to do so with means that articulated like precision machinery. Otherwise, everything would collapse.

Facing Franco-Russian encirclement, German plans rested on the destruction of one of the adversaries before concentrating on the other. Moltke the Elder (1800-1891), the victor of 1871, planned to attack Russia first. His successor, General von Schlieffen (1833-1913), reversed this strategic plan, as immense Russia seemed impossible to defeat quickly. He therefore planned to crush France in a few weeks, thanks to his famous "plan".4 The "Schlieffen Plan" adopted in 1906 still prevailed in 1914.

Facing Russia's general mobilization on July 31, Germany, feeling mortally threatened, declared war on it on August 1. But it had to immediately attack France, and therefore declare war on it if it did not do so first (it would have done so anyway). It also had to violate Belgian neutrality, which would inevitably provoke England's intervention in the conflict.

Although with less acuity than Germany, the other powers were subject to the same logic of the mobilization system of immense conscript armies. This raised problems of transport, incorporation, material distribution, routing, and deployment that required between 15 and 25 days. The decision taken by a power to mobilize therefore represented a mortal danger for its potential adversaries. Unless taking the risk of being caught off guard and annihilated without even being able to fight, the response could only be to mobilize in turn and without delay, and then, applying the best principles of military art, to take the initiative to surprise the enemy.

In all capitals, during the decisive Councils, generally mediocre politicians yielded to the technicians (chiefs of staff). And it was not on political criteria that the latter relied, but exclusively on technical criteria. We can thus say that the outbreak of the 1914-1918 war was the first triumph of the new technostructures over political thought or designs. Such "progress" can be appreciated by its results...

Originally published in Enquête sur l'histoire no. 12, Autumn 1994.

Translated by Alexander Raynor

Buy Dominique Venner’s books

Le Procès de Salonique, Éd A. Delpeuch, Paris, 1927.

On Stolypin's work and the circumstances of his assassination, see the article that Dominique Venner published in Enquête sur l'histoire no. 7.

On the circumstances of the attack, one can refer to Alain Decaux's article in Enquête sur l'histoire no. 7.

See Philippe Conrad's article on the Battle of the Marne.