Yukio Mishima: Action and Art

Chōkōdō Shujin examines the tension between personal artistic drive and national characteristics, as exemplified by Yukio Mishima’s life and work, which epitomized the spirit of ancient Japan and the pursuit of beauty in creative expression and deeds.

It is quite plausible that an art historian or art critic can look at the work of an individual and see in it a certain tendency in the taste of the entire nation to which the artist belongs, or in the way he views or expresses certain sentiments. However, if an artist, in creating a work of art, is conscious that “I am Japanese, so I must express the taste of the Japanese,” he is misguided. When an artist is engaged in production, he should have only a burning desire to create with all his strength. There should be something present within him that is so full that it bursts forth, and all of his consciousness must be concentrated only on giving it form and manifesting it outwardly. From the outside, through the finished work, there may be something uniquely Japanese about it. However, this is not the artist’s concern. The artist only shows what he intends to show. Alternately, the artist may study the ancient arts of the country, and gain some hints or inspiration from them. In this way, traces of the ancient art of that country will naturally appear in that artist’s work, or a certain spiritual light may be felt between the two.

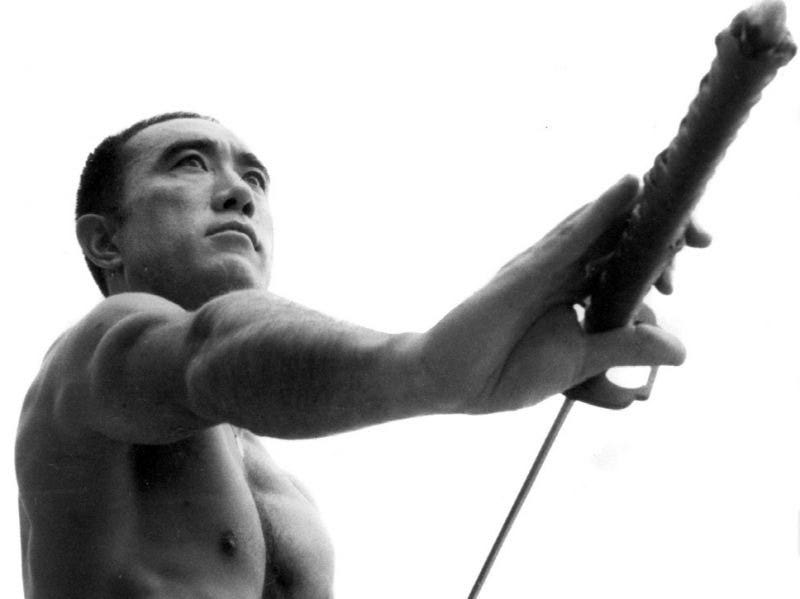

But such scrutiny is the province of critics. It is only through ancient art that the artist can hint at what he has sought but has not yet achieved, and what he has not yet been able to manifest. To put it another way, the artist and the ancient arts have found a point of agreement. Or, he recognizes his own reflection in the ancient arts. In this case, once he begins the process of creation, the ancient arts must disappear from his consciousness. In no individual artist is this better expressed than in the life and death of Yukio Mishima, who found within himself both the duty and the will to live and die beautifully, for his nation. In doing so, he fully embodied the spirit of ancient Japan. His act of seppuku on November 25, 1970 can be seen as the pinnacle of both art and action, a glorious convergence of mind and body. “Even after enduring and enduring, rising up with firm resolution once the last line of what you are supposed to protect has been crossed is what it means to be a man, what it means to be a warrior,” Mishima said in his final speech, addressing the Japan Self-Defense Force garrison at Ichigaya.

Mishima’s death was the utmost manifestation of his existence as an individual; as a man, and as an artist.

While it is obvious to any that Mishima was willing to die for an action that he knew would amount to nothing, he did not seek to die a “Japanese death,” although the result is the same. His death was emblematic of centuries of Japanese tradition. Mishima chose the manner of death that was the most suitable to convey his message: that his nation should arise and be liberated from the constraints forced upon it by the Americans in the aftermath of the Pacific War. In his supreme action, Yukio Mishima acted as both warrior and artist. His death was a symbolic one, even if he was not conscious of all of the particulars of this myriad symbolism at the time. “Eternal art is the action of the eternal personality without dependence upon artificial sensation or action,” the art historian Sôetsu Yanagi wrote in his treatise The Revolutionary Artist. Mishima was one such artist. There was no artifice in his death. Mishima simply did what was natural to him as a man and as an artist. He chose the most suitable manner of expression for the times.

“Only art makes human beauty endure,” Mishima wrote in Kyoko’s House. First and foremost, art is dependent on expression. Indeed, much like action, all art is dependent upon expression, or depiction. The same applies to the selection of materials for depiction. For example, a painter creates a watercolor painting. This is because the painter feels that what he is trying to express at that moment is best expressed in watercolor rather than in oil, pastel, or anything else. If the artist believes, for example, that watercolor painting is in harmony with the taste of the Japanese people, and that is why he chose watercolor, then he is the most unfaithful of painters. Or, he is not qualified to be a painter. Artists do not make watercolor paintings for such external reasons. The life of watercolor painting must lie deeper than that. Similarly, if a sculptor decides that wood carving is more suited to Japanese taste and therefore chooses wood over marble, this is also a fallacy. If something is unsuitable for marble, unsuitable for bronze, and can only be adequately expressed by wood, then wood should be chosen. It goes without saying that, in making a work of art, an artist should not have any other consideration than to give it the most appropriate form for what he intends to express. For Mishima, this was the destruction of the body. He began his life as a frail, skinny “literary youth.” Although he had always cherished a romantic impulse towards death, he recognized that such a body was not an appropriate means of expression for such an action, and his life, along with his beautification of his body through martial arts and weight training, was a culmination of his desire for this. In Sun and Steel, he wrote, “Nothing could have accorded better with the definition of a work of art that I had long cherished than this concept of form enfolding strength, coupled with the idea that a work should be organic, radiating rays of light in all directions.” Mishima’s death was the utmost manifestation of his existence as an individual; as a man, and as an artist.

“The flower that opens on the battlefield is formed only by the hand of a poet with learning and artistic ability,” wrote the critic Yojūrō Yasuda. The above is based on the perspective of the artist’s psychology, but if we look at the facts of cultural history, then it is apparent that there is a national character in art as well. However, the nature of the national character can only be determined after thorough historical research, and it is not something that can be determined rashly based on a few minor details, such as appearance. Yasuda once wrote that the commonplace observations about the Japanese taste for simplicity and neatness have a major flaw. Mishima agreed with this assertion, remarking that when Westerners view Japan, they have only the desire to see the chrysanthemum, rather than the sword. Other critics have suggested that the taste for tea ceremony has a significant relationship with the Japanese national character, but this is dubious. The tea ceremony, as it is commonly referred to, took shape during the period of cultural decadence known as the Warring States Period, or the Sengoku era (1467-1568), and although it was in tune with some aspects of the decadent mood of that time, it was not originally a hobby of any real significance. The reason why this was done in the Tokugawa period was not because of taste, but for other social reasons.

I once read a rather trite observation that the Japanese are happy to write 31-character tanka and 17-character haiku, and that they like small, easy things, but this is also dubious, and there is no doubt that there are other reasons for writing tanka and haiku. Namely, the existence of death poems, or jisei. Mishima’s is as follows:

A small night storm blows

Saying “falling is the essence of a flower”

Preceding those who hesitate.

It is unnecessary to go into detail here, but it is worth mentioning that national character cannot be so easily dismissed. Moreover, there is no need for artists to keep such vague and ambiguous theories of national character in mind. Taste should come naturally to the artist; otherwise, it is merely an affectation. Not only that, neither the national character nor the taste of the people can remain fixed. In short, they are cultivated through the actual lives of the people, and are a reflection of the lives of the people. So as long as the people live, they will constantly change along with the changes in their lives. If it stopped moving, the nation would calcify and die. “History is a record of destruction. One must always make room for the next ephemeral crystal. For history, to build and to destroy are one and the same thing,” Mishima wrote in Spring Snow, the first in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy. It is the artist, however, who builds and gives new form to the national taste, and pours new life into it. Perhaps artists do not do so consciously, but history shows that they nonetheless do so. From this point of view, artists should not be obsessed with past national tastes. Rather, the past should be alive within the artist himself.

Another point to consider is that, since artists are also citizens of the nation, their national character must reside in them, even if they are not consciously aware of it, so any artist’s honest work is a manifestation of his national character. National character does not exist outside the mental lives of the people living today, but is expressed by the artist in the field of taste. The people’s desire to gain new life in their hobbies becomes an inner urge to open up new horizons, and is embodied in artists. In a word, the artist is the arbiter of taste. Therefore, the artist who is single-mindedly trying to express himself is unconsciously realizing the needs of the nation. This is especially evident in the literature of Yukio Mishima, in his nationalistic pieces such as “Patriotism” and “Voices of the Heroic Dead.” The artist does not speak of national identity in terms of knowledge, but rather shapes it as a living art form.

Above all, in art and in life, Mishima sought beauty and purity. Sublimity is a characteristic of the influence of beauty. People are concerned with their daily lives, and everyday life is a life of immediate affairs. The average man or woman is buried in the accumulation and forgets the non-presumptive aspect inherent in life itself. “I’d be glad to show anyone who’s willing to be shown how much-repeated suffering we have to endure just in order to fool ourselves, all of us who are living in these depraved times,” Mishima wrote. And in order to drive away the unbearable depression, they quickly cheat for a moment by fishing for lowbrow entertainment, or for things that make them laugh or give them a sense of danger. In reality, they are not satisfied with anything. In the end, Mishima wrote, they always feel as if they are being ridiculed by such things. Deep down, perhaps they realize that they are being ridiculed, and yet they continue to pursue such distractions. Everyday life is so dull, bitter, and dry that they have no choice but to look at it. “Of course, living is merely the chaos of existence, but more than that it’s a crazy mixed-up business of dismantling existence instant by instant to the point where the original chaos is restored...,” Mishima wrote in The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea. In this modern era, most have lost touch with beauty and sublimity.

Once a person loses touch with beauty, he abandons the existence of his own intrinsic aesthetic activity, that is, the artistic spirit itself, and seeks only what exists outside of the self. This is the result of a shallow, materialistic society that has lost touch with its history. Art then becomes a commodity, a product, created to satisfy their desire to possess it. This is why the appreciation of paintings, calligraphy, and antiques is always accompanied by an interest in price. When the average man or woman hears the price of a painting or calligraphic work is several thousand dollars, they come to appreciate it even more; this is a sign of their lack of innate taste. It is a characteristic of the artist to be interested in the appreciation of a work of art without any price in mind. The difference between a pure artistic consciousness and a “collector’s” consciousness is often expressed in such a delicate point.

In such a state, because one’s intrinsic sense of beauty is inactive, the world is left to others as far as beauty is concerned. Clothing designs are influenced by the hands of merchants, urban architecture takes on any form it chooses for the sake of convenience and lack of imagination, and the publicity becomes more and more outrageous. Everything we see and hear in this world is filled with things that are different in nature from true beauty, and yet we are deceived into believing that they are of the same quality as beauty. Instead, they are content with their expendable resources, with no concern for anything else.

If this state of affairs continues for long enough, a kind of popular nihilism will pervade, superstition will prevail, and people’s minds will be in turmoil.

The reason why the awakening of the artistic spirit, that is, the independent activity of the sense of beauty buried within each individual citizen, is more important today than any other problem in the world of the arts is that it has the most fundamental salvific significance for national life. This is because it has meaning. The spirit of the arts is not something that exists outside of the people of the nation, but is the spiritual power within each of them that allows them to immediately and unobtrusively observe and appreciate the daily routine of life itself. It is mental strength that makes things possible. The mind of art is the condition in which the suffering and troubled self, while suffering from life and its various indignities, can be viewed and tasted from a world that is not at hand. It is truly the same as life, and yet it is not dictated by life, but rather makes life more prosperous and beautiful. It is a mind that does not panic and is not surprised in case of emergency. The spirit of the arts does not liberate us from this world as religion does, but makes us experience the world as it is. It must transform everything into beauty. As Mishima wrote in The Temple of Dawn, “Beauty stands before everyone; it renders human endeavor completely futile.”

立石一真氏など戦後国を再建した挑戦者たちと比べれば、三島はただのクズでしょう。愛してやまない(らしい)日本の社会に貢献するような仕事が嫌で自殺した甲斐性無しのくせに、西洋人がそれを美化してまるで聖人扱いだ。