Who Will Judge the Judges?

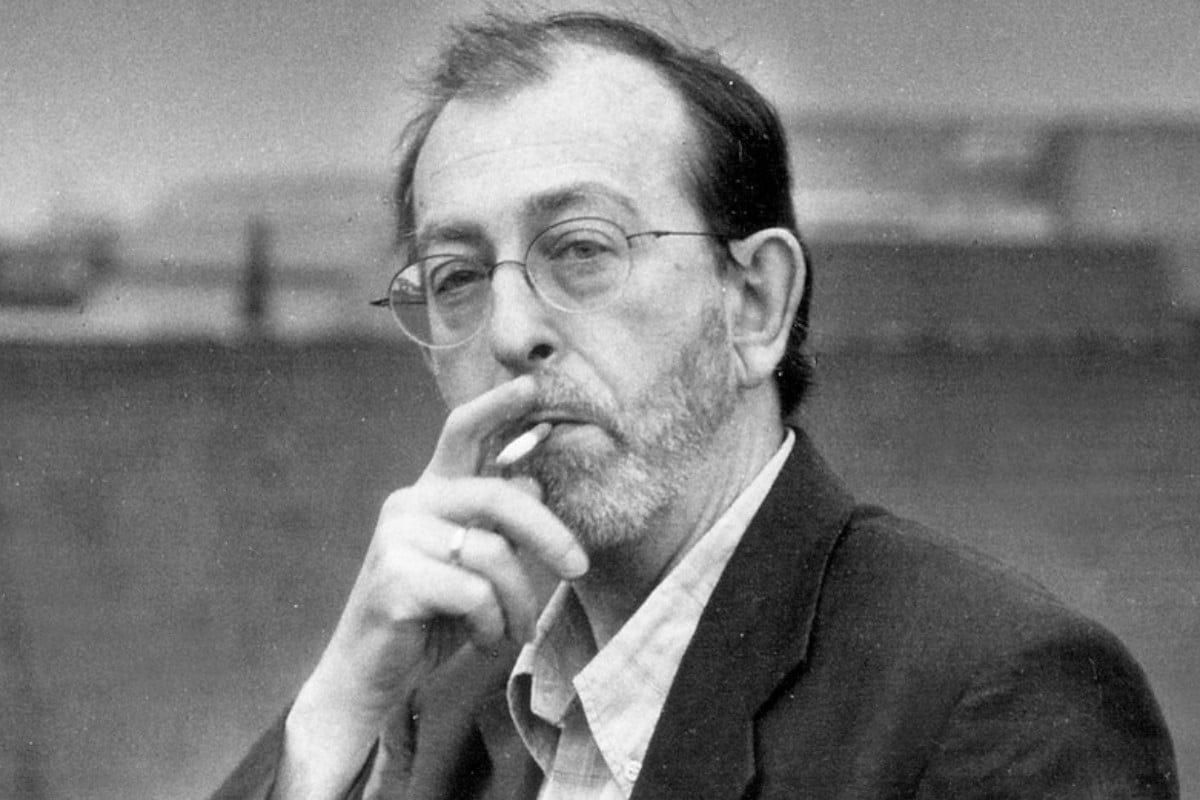

by Alain de Benoist

Alain de Benoist examines recent judicial interventions in electoral processes across multiple countries, arguing that such judicial actions represent a fundamental assault on popular sovereignty, where unelected judges effectively decide who citizens can vote for. The problem, de Benoist contends, is the concept of the “rule of law”, a liberal ideological construction that subordinates democratic will to abstract legal norms and human rights doctrine, ultimately giving judges the final say in political matters rather than the people.

Beaten by Joe Biden in 2020, Donald Trump claimed he had been “robbed” of his election due to various fraudulent maneuvers endorsed by judges. In Turkey, the main opposition representative, Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, favored for the next presidential election, was thrown in prison. In Côte d’Ivoire, the presidential favorite was simply struck from the electoral rolls. We have also seen Romanian judges annul the first round of the November 2024 presidential ballot, won by Călin Georgescu, for suspicions of “Russian interference” that remain to be proven, then ban him from running in the following election. The ultimate recourse of the ruling class to prevent the progression of dissenting voices is apparently to prohibit their representatives from participating in elections.

The Law Against the Peoples

The French case is not very different. By declaring Marine Le Pen ineligible, the judges dynamited the presidential election two years before it is held, using two scandalous procedures: ineligibility first (it is not normal that a criminal court can pronounce political sanctions), and above all provisional enforcement, as it amounts to anticipating the result of the appeal procedure.

But make no mistake: making Marine Le Pen ineligible was only a means, the true goal being to prevent citizens from voting for her, at the very moment when polls, attributing 37% of votes to her in the first round, gave her strong chances of winning in the second. Through Marine Le Pen, it is the considerable mass of her 12-15 million voters who were sanctioned first and foremost.

Now, it is not for judges to decide who can seek voters’ support, that is, for whom citizens can vote. Magistrates do not have the right to determine what is ideologically and democratically acceptable in their eyes, this right amounting to depriving the people of it, the sole and unique holder of the freedom to elect whom they want. By weighing on the presidential election, that is, on the orientation of the country’s political life, judges set themselves up as electoral arbiters, which is not their role. This is yet another illustration of the elites’ contempt for the people, and especially of their will to govern against them. And it is also a perfect illustration of the “rule of law coup d’état,” to which the central dossier of the last issue of Éléments was devoted.

“BY PUTTING DEMOCRACY UNDER GUARDIANSHIP, LIBERALISM GIVES THE LAST WORD TO JUDGES. JUDGES ENGAGE IN POLITICS, BUT WHO WILL JUDGE THE JUDGES?”

As Bruno Retailleau said, the rule of law is “neither intangible nor sacred” – for the simple reason that it is only an ideological construction, liberal in this case. Born in the 19th century, the rule of law (Rechtsstaat) is not simply a state “that subjects itself to a regime of law” (Carré de Malberg). Hans Kelsen saw it as a state “in which legal norms are hierarchized such that its power is thereby limited.” The rule of law is in fact the opposite of the law of the state. However, the State cannot be subject to the law it enacts, since it is its foundation, it alone possesses the necessary force to guarantee it, and the law of the State can only aim to preserve it.

The rule of law imposes the hegemony of norms. The supreme norm, supposed to apply to all, gives the last word in matters of political decision to the juridical. In doing so, as Christophe Boutin writes, “the judicial decision, divesting itself of normative power, modifies the effect of the rule of law according to its own will – and the rule of law cuts itself off from its democratic legitimacy to be nothing more than the expression of the ideology of a caste.”

The final result is that it is no longer democracy that equips itself with a Constitutional Council to verify the conformity of law to the text of the Constitution, but democracy that is supposed to be produced by the rule of law. The latter judging political decisions by the standard of the ideology of human rights – “the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Council,” observes political scientist Pierre Manent, “tends to absorb the rights of the citizen into human rights” – the only conceivable democracy becomes at the same time liberal democracy, where the defense of individual rights prevails, in case of conflict, over popular sovereignty.

The idea of the rule of law ultimately rests on a dualist distinction between the State and the Constitution. These two concepts no longer overlap existentially, but are clearly opposed: the Constitution positions itself from the outset as superior to the State, whose powers it seeks to limit, in accordance with liberal doctrine, and the State must bow before it. The functioning of democracy is thus placed under the condition of not contradicting the ideology of which constitutional texts are the bearers.

To those who hop about like goats intoning, in litanic fashion, in the open air of the rule of law as if it were a creed, we must recall: 1) that democracy is not based on the notion of “fundamental rights” – the claim to make each individual’s desire a rule for all and the refusal of any “discrimination” – but on that of the sovereignty of the people, the first condition for a common interest to be formulated, which implies a distinction between citizens and non-citizens; 2) that judges should not judge in the name of rights, but in the name of the people; 3) that the democracy of rights leads to social disintegration, while true democracy consecrates the power of the popular community, starting with the power to change the law, even if this change infringes on certain rights.

By putting democracy under guardianship, liberalism gives the last word to judges. Judges engage in politics, which shows that the separation of powers does not guarantee their ideological independence. But who will judge the judges?

Originally published in Éléments no. 214, June-July 2025

Translated by Alexander Raynor

All true and important But like most critiques of current judicial trends, this one limits itself to the realm of headline news. In some western countries -- especially the Anglophone countries from which much of this is exported (the US and Canada above all) -- local courts that are never seen on the media radar screen are far more corrupt, predatory, and politically captured. And they inflict far greater harm on the lives of ordinary citizens who have no voice to speak out.

those who gather the rope