Twin Peaks: Protect Your Kids!

by François-Xavier Consoli

François-Xavier Consoli pays tribute to David Lynch (1946-2025), recounting how he revolutionized television by blending detective fiction, soap opera, and surreal horror into a haunting portrait of the hallucinations and nightmares that lurk beneath the veil of modern American suburbia. Dare to peer into this ominous vision of how generations fare the modern world — and protect your kids!

In the late 1980s, a talented screenwriter and a genius filmmaker meet. Together, they develop an imaginary town, lost at the edge of the border between Canada and Uncle Sam’s country, dominated by two twin peaks: Twin Peaks. Mark Frost and David Lynch don’t know it yet, but this all-too-brief series will change the television landscape. Better yet! It will blow television apart. Prematurely stopped by the ABC network, Lynch will have the audacity to come back for seconds in 2017, with his last major work, Twin Peaks: The Return, 25 years after the end of the second season, picking up where everything left off. In a kind of dance between detective fiction and the fantastic lies undoubtedly one of the best series about America and the family. Hide your kids! Because beneath the sunny appearances, the comfort and security of comfortable homes lurks the anxiety of the strange. A tribute to a pure artist of cinematography, who passed away on January 16th, 2025.

A few days before succumbing to a heart attack at the beginning of this year, 2025, David Lynch is forced to evacuate his home threatened by the fires ravaging the hills of Los Angeles. The fire only accelerated his emphysema. In about ten films and several series, Lynch rose to the rank of one of the great directors, his name becoming a true adjective: the “Lynchian” style – the “first popular surrealist,” according to the famous critic Pauline Kael in The New Yorker.

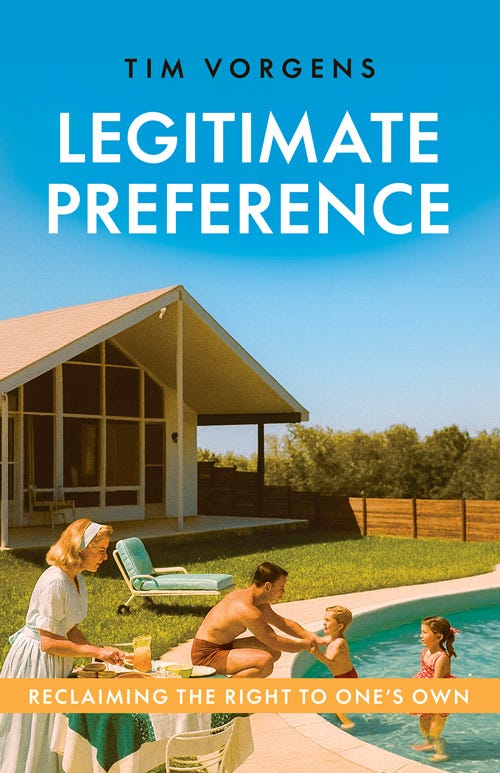

A dreamy kid, born in the wide open spaces of Montana in 1946, he describes his childhood as a “sort of waking dream,” an idyllic moment. 1950s America would be this defining age, which he would pay homage to in many of his films. In addition to typical dinners, donuts and jukeboxes, young David, shuttled with his family to different states across the country, bathes in the optimism, the euphoria of rock ‘n’ roll and limitless consumption. But under the surface, something swarms, crawls slowly, as if, under the lacquered decor and the curtain of joyful appearances, other worlds, other troubling truths, were just waiting for a fateful event to reveal themselves. The swarming malaise, that’s what interests David Lynch!

The American Ideal

Everything is beautiful in Twin Peaks, a town in Washington State. Everything seems comforting. Grandiose landscapes, majestic sequoias, a placid small community of inhabitants, nestled in a town without stories where the smell of good cups of coffee reigns, overlooked by soporific mountains. A place where time seems almost to have stopped.

One morning like any other, Pete Martell, the somewhat self-effacing husband of the local sawmill owner, goes fishing. At the water’s edge, he discovers a large plastic wrapping containing a corpse. Sheriff Harry S. Truman (like the immediate postwar president) and his deputy rush to the scene. From the plastic wrapping emerges an imperturbable and angelic face turned blue by the cold: Laura Palmer, the town’s beloved child. For this postcard town, it’s a trauma. To attack Laura Palmer, the seraphic teenager, devoted and loved by all, is to attack Twin Peaks. The case quickly exceeds the local police force. FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (the role of his life for actor Kyle MacLachlan) is dispatched to solve the macabre murder. Under the varnish, he will discover much more than he thought. The stage is set.

The ‘50s Americana installs us into an all-comfort cocoon: it’s a criminal case like so many others. But from the beginning, Twin Peaks stands out. Because it’s a series at war. All the codes of the police series are there: murder, sheriff, FBI. The high school series too: the jock, the jackets and pleated skirts, pom-pom girls and requisite “rebellitude.” Add to that the business soap opera à la Dallas: financial schemes, drug trafficking, business magnate reigning supreme over the town’s grand hotel. And finally, the village chronicle: smiling waitresses, convivial breakfasts, archetypes of everyday characters (the mechanic, the doctor...). Finally, it’s a show like any other.

But no. Because Twin Peaks is only appearance. Under the police case, the routine of high schoolers and the idyllic setting hide secrets; under the apparent tranquility of living rooms and bedrooms, dark truths will not take long to reveal themselves in broad daylight. Lynch himself reminds us:

“The home is the place where everything can tip over...”

In 1986, his film Blue Velvet ends with a robin taking us out of the nightmare. In the Twin Peaks credits, Angelo Badalamenti’s sweet music begins with a bird: a Bewick’s wren, a species typical of the northern United States. Lynch will thus employ the “language of birds,” in other words the language of secrets, to bring us into this apparently banal and tranquil world. But...

In Twin Peaks, Lynch constructs a true saga about America and the family. A successful mythology. The most esoteric propositions take power over the most democratic medium: television.

Behind the Curtain, the Nightmares

The innocent victim, Laura Palmer, a perfect little teen, is the central pivot of the series. In a sort of dancing round, the whole small world of Twin Peaks will start to spin. The tragic end of the town’s beloved daughter is a transition. Like any initiation, things will unfold in pain. Under her irreproachable girl airs, a fire of horrors consumes the teenager. Behind the white and luxurious facade of the Palmers, at the family table, nothing is right. Under the features of Leland Palmer, respectable lawyer in every way, lurks his daughter’s tormentor: a man possessed by Bob, incarnation of evil—perhaps even Evil with a capital E. Passive and herself traumatized by this perverse family mechanism, Laura’s mother isolates herself, drugged by television watching. Prisoner of hygienist and puritan appearances, perfectly aware of the fatal fate that awaits her, making the character all the more Shakespearean, Laura, beautiful celestial kid, sinks into the darkness of depression, drugs and prostitution, as shown with great crudity in the film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), an unloved prequel upon its release.

Even if the viewer is not aware of what Laura goes through in the series, the episode where her father confesses exposes in broad daylight this profound terror, this cruel impulse of America, this deaf perversity that sleeps, and of which childhood will be the victim. Allegory of grief, Laura will end up prisoner of the Black Lodge, the place of curse, of the Doppelgänger, the cursed double, where time and space come apart. Where even the best coffee is undrinkable. This place of opposites will weigh throughout the show on Twin Peaks’ daily life.

Death is the moment of passage to adulthood. Like during the nighttime road accident scene in Lynch’s film Wild at Heart (1990), where the two young protagonists on the run will see death before their eyes. It’s the end of innocence.

Laura’s murder sets up two groups seeking to solve her assassination: the high school teens and the sheriff’s office adults. Mirroring our victim, her best friend yet jealous, Donna. Sweet and beautiful like Laura, but much more self-effacing and childlike, the “friend in the shadows” is loved and cherished by her family, notably her father, the town doctor.

This “ideal family” is the counter-reflection of the Leland dysfunction. Donna’s investigation to solve the mystery will come at the price of losing her illusions, discovering the secrets of this friend she thought she knew. Donna will learn to discover herself, lifting the veil on her father’s true identity. To conduct her investigation, Donna is supported by James. A lost kid who dropped out of high school, he’s Laura’s secret lover. Alcoholic mother and unknown father, he’s raised by his uncle Ed Hurley, the mechanic. He thus has two passions in life: his motorcycle and Laura. The latter’s death only stirs within him the demon of instability, pushing him to constantly mount his steed to sail along the roads. By leaving Twin Peaks, he flees his wounds, only to take them with him.

Lost Adults

Laura’s official boyfriend, Bobby, is the rebel archetype. The nonchalant wise guy, son of strict officer Garland Briggs, he perfectly illustrates the father/son confrontation. Despite his facade of assurance, Bobby is victim of manipulation by business-minded adults, like Benjamin Horne and the Renault brothers. His salvation will come from the father, one of the rare adult figures in Twin Peaks, deeply loving and eager to accompany his son in this troubled world.

After Laura’s death, Bobby finds comfort in the arms of the beautiful and young Twin Peaks diner waitress, Shelly. Too soon left to herself, Shelly married as a teenager the tyrannical Leo Johnson, absent trucker and protective figure corrupted by violence and trafficking. The conjugal tormentor, after an attempted murder, will end up in a vegetative state and used as an infantilized puppet by Agent Cooper’s sworn enemy.

Finally comes the last teenager of the group, Audrey, “fatal teenager” and spoiled daughter of the town’s rich real estate speculator, Benjamin Horne. Desperately seeking paternal attention, it’s by taking inconsiderate risks to solve Laura’s murder that she finally discovers her father’s face. Attracted to the seductive Agent Cooper, she wants to prove what she’s capable of, venturing into the One Eyed Jack, local brothel run by her father, where she’s drugged and sequestered. This violent transition to adulthood marks a passing of the torch between daughter and patriarch, the latter experiencing a period of true regression where he’ll think he’s a Confederate officer, transforming his office into a battle scene in season two.

As for the adults, everything seems to overwhelm them. The parents, of course, but also the police authority figures. Only Agent Cooper, through his unorthodox methods and his desire to see beyond appearances, reminding the viewer of the wise necessity to enjoy what life can bring us that is beautiful, progressively manages to pass behind the curtain, leaving his FBI colleagues disconcerted. The most marked opposition between the troubled world of children and adults is best illustrated with the character of Sheriff Truman, whose very patronym recalls a protective America that’s moving away. An upright and honest man, his “good guy from around here” bonhomie makes him blind and powerless in the face of the dark reality festering in his town.

The link between adult and childhood remains thanks to three characters. Nadine, accidentally made one-eyed during her childhood, wife of solid mechanic Ed, terrified at the idea that he’ll abandon her. Her suicide attempt in the second season will make her mentally regress to adolescence, a metaphor for stolen puberty. Finally, Andy and Lucy, the bumbling deputy and naive secretary. It’s no coincidence that they form the most innocent couple, even childlike, in the series. But thanks to whom the most minute details escaping adults end up being discovered.

Childhood Leaves Traces

“The past dictates the present.” — a lapidary reply that’s not at all innocent launched by Agent Cooper at the end of the third season, finally awakened, delivered from the Black Lodge’s fate.

Twenty-five years after Twin Peaks was halted, David Lynch, an artist in the true sense of the term, realizes a true televisual happening: he relaunches the series with the same actors, still in this good old town. As he was able to do with his unclassifiable Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholland Drive (2001), this third and ultimate season is the completion of his Möbius strip, whose two interchangeable faces form only one and the same reality, the end rejoining the beginning, in an infinite dance.

Return to Twin Peaks, but time has done its work. The decor certainly hasn’t moved, but evil has spread. The action is no longer only in Twin Peaks, but in different places across the country. Violence has escaped from family homes, poverty has dissolved the bucolic image of the fifties, now a distant memory. Years later, the children are adults. But marked. Bobby, the rebel, has made his transformation. As is fitting, the military man’s son has become another authority figure: he’s deputy sheriff in Twin Peaks. With beautiful Shelly, they had a daughter. Bobby’s balance isn’t enough for this eternal waitress all surface, incapable of taking care of her daughter. Audrey’s violent passage to adulthood will have left traces, and even on her son, a new incarnation of evil. Despite her steel character, this kid now adult remains broken, locked in a troubled reality. James the orphan has returned. He’s put away his steed, but the past still haunts him. He no longer wanders the roads, but in his memories. The most “balanced” are Lucy and Andy, faithful to the sheriff’s post, married and parents of Wally Brando, carbon copy of Johnny Strabler, protagonist of The Wild One embodied by Marlon Brando (1953).

Out of his curse after twenty-five years, Agent Dale Cooper will finally find peace with a substitute family. He returns one last time to the past, to Twin Peaks, where it all began, to defy time, to save the angel Laura Palmer. The loop is closed.

In Twin Peaks, Lynch, with his child’s gaze, constructs a true saga about America and the family. A successful mythology, where he had failed with Dune in 1984. The most esoteric propositions take power over the most democratic medium: television. An artist! Whatever happens, Lynch reminds us that it’s impossible to get rid of family heritage. But sometimes, often even, it’s the little gifts of life that count the most, as Officer Garland Briggs, Bobby’s father, tells us so well during one of the most beautiful scenes in Twin Peaks, where he tells him about a dream in which he saw his son:

“My son was there. He was happy and carefree, clearly living a life of joy and profound harmony. We embraced—a warm and loving embrace, without any restraint. We were one in that instant. My vision stopped. I woke up with tremendous optimism and great confidence in you and in your future. That was my vision, it was yours. I’m very happy to have had the opportunity to share it with you. I wish you nothing but the best, always.”

Protect your kids...

Originally published in Éléments no. 214, June-July 2025

Translated by Alexander Raynor

Superlativo!