Tribe or Empire?

by Askr Svarte

Askr Svarte critiques the “Tribe vs. Empire” framework that pits free communities against imperial order, examining the philosophical and historical precedents of sacred hierarchy to argue that the traditional imperial archetype is just as relevant for building small-scale, close-knit communities outside the modern system today.

“Tribes vs. Empires” — this is the question posed by Stephen McNallen in his discussion of Rome’s conquest of the Germanic tribes. McNallen sees the Roman Empire’s conquests as the advent of a mighty and powerful (repressive) system that subjugated small, free Germanic peoples. McNallen and the part of Asatru that follows him as their leader, therefore, stand on the side of peoples, the “folkish” side in the struggle of peoples against empires.

Here it is necessary to deliberate terms in detail. The English word “tribe” goes back to the Latin tribus, i.e. “clan”, “race”, “genus”, “people”, “community.” In the context of McNallen’s discussion, this concretely concerns the ancient Germanic tribes in their pre-state rod-clan structure. McNallen understands “Empire” as referring to the materialist, capitalist system, which fully corresponds to the French sociologist Alain Soral’s understanding of Empire. For Soral, the modern, anti- traditional System (of Modernity) - for defining which Soral directly relies upon and cites René Guénon - emerged in the Enlightenment and at the contemporary stage represents a complex combination of capitalist, political, ideological, and mafia-network structures which repressively administrate the world. Soral calls this System “Empire”, but such has nothing to do with the Old World and its Empires, hence the need for a clear distinction in the use of the same term for different phenomena.

Soral’s Empire is McNallen’s modern Empire which pagan religions and Asatru oppose. McNallen, however, traces the roots of this Empire back to the Roman Empire, and thus emphasizes that the difference between Rome and Empire à la Soral is “cosmetic.” Therein lies the nuance of McNallen’s perception of the Empire-System: when he speaks of the modern world, the contemporary US, and the global System, he is fully in line with the Traditionalist discourse of Alain Soral. When he speaks of this System in terms of Antiquity, in Rome, he commits a fundamental, paradigmatic error by equating two Empires that differ in nature.

Soral’s modern Empire-System and McNallen’s understanding of Rome’s Germanic conquests are more consistent with the modern notion of “imperialism”, which means the economic and military-political expansion of powerful states into colonialism and the suppression of the indigenous populations of colonies up to the point of systematically exterminating them (as happened in America, Australia, and India). With this approach, McNallen’s democratism is rooted in a confused equating of two different phenomena. There is no point in equating the imperialist stage of capitalism as described by Thomas Hobbes and Vladimir Lenin with the pagan imperialism of Julius Evola, which is built on entirely different, traditional premises.

Empire in the traditional meaning is in essence the maximal expression of Sacred Hierarchy and the Due on the level of the State. In other words, Empire is the elevation of the Due and hierarchy to being State principle. In line with Plato, Empire is the form of just State that has a monarchical form of governance. The principle of Empire does not contradict the principles of communal hierarchy and organization, but is distinct from them in terms of level, complexity, framework, and organization. The Emperor of the State is akin to the tribal leader, the head of the community (the Old Slavic mir) or clan, the army is the warrior band, the Männerbund, and farmers and artisans are present in both structures.

Just as Plato’s dialogue revealed equivalencies on all levels, the parallels between Empire and tribe/community can be continued on the level of the family and the individual. Empire is the pinnacle of pagan statehood, the maximum of the Political of Tradition. Smaller states, tribes, or communities differ from Empire in scale and power, but they are structurally complementary if, as Plato articulated, they do not deviate in the direction of unjust forms of governance and order. It is telling that Rome’s imperial policy did not entail the ethnocide of conquered peoples, but rather included religious pluralism, the expansion of imperial cults, and the syncretizing of traditions. Soral’s Empire-System, on the other hand, is the ultimate version of the Anti-Empire, absolutely unjust and based exclusively on material interests.

No less suggestive is the fact that it was the Germanic peoples who finally crushed the Christian Western Roman Empire and later, upon absorbing the Hellenic heritage, reproduced a whole network of Christian Germanic Empires up to the point that nearly all of the royal houses of Europe, including Russia’s, traced their genealogies back to Germanics or were German in origin.

The structure of Empire fundamentally changed with the Christianization of Rome, which predetermined the decay and fall of the Empire and then, coupled with Germanic passionarity, the restoration of Empire in the form of reproductions (as opposed to pagan incarnations) of its structures in Christian guise and theological justifications. The fate of the Eastern Empire, however, was different from that of the Western. The Byzantine Empire outlived the Western Empire and presided over the formulation of a new Christian doctrine which once again substantiated the Sacrality of the figure of the Emperor and the role of Empire. Such can be seen as a structurally pagan (dual-faith) relic, since Empire itself was alien to Christianity in its political dimension. The theological doctrine of the Katechon (Greek: κατέχων), “the withholding one” or “the restraining one”, had its roots in the New Testament, in 2 Thessalonians 2:6-8:

And you know what is now restraining him, so that he may be revealed when his time comes. For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work, but only until the one who now restrains it is removed. And then the lawless one will be revealed, whom the Lord Jesus will destroy with the breath of his mouth, annihilating him by the manifestation of his coming.

Verse 2:7 says that the Antichrist will not come to rule the world as long as there is “the restraining one” (ὁ κατέχων) whose very existence and righteousness prevents such. Orthodox Christianity understands Katechon to be the Holy Spirit that is present in the world until God takes it away from people in the Apocalypse. Another interpretation understands the “restraining one” politically as the Emperor and Empire. This political doctrine of Katechon found the greatest resonance in Russia, where it became consonant with the doctrine of the Third Rome and has come to serve as a justification for monarchism and an Orthodox “revival” at the contemporary stage of Russian statehood.

Identifying the emperor with “the restraining one” renders his figure and authority moral in nature, which contradicts pagan Dharma, the Sacred status of the Emperor as a God, and the fundamental freedom beyond the Abrahamic categories of Good and Evil that are alien to the pagan worldview. Yet this moral nature of the Emperor fits well with the creationist reproduction of imperial structures, with paganism displaced into the periphery. The relationship between secular Emperor and spiritual Patriarch lined up into a dual power, a symphony of powers, wherein the Patriarch administrated the internal affairs of the Church and the Emperor was, in the words of Constantine I, “the steward of the external affairs of the Church”, i.e., state and foreign policy.

The Western world took a different path which manifested conflict between these two authorities: the spiritual authority of the Catholic Popes and the secular authority of the kings and emperors of European states. In Italy, this situation took on the form of two parties, the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, the former being supporters of the supremacy of Papal authority over the worldly authority of kings and apologists of theocracy, while the latter insisted on the Pope’s subordination to the Emperor and advocated the supremacy of imperial power. Historically, the Ghibelline party suffered defeat. In the modern era, Ghibellinism would find an ardent apologist in Julius Evola. Ghibellinism on the whole expresses the spirit of the second estate, the primacy of martial, royal power over the spiritual, which in Evola’s case overlapped with his rejection of Catholicism. On Christianity and the Roman cult of the Emperor, Evola wrote:

Julian yearned for the realization of this “pagan” ideal in a sturdy unitary imperial hierarchy furnished with a dogmatic fundament, complete with disciplines and laws. The emperor would be the summit of its priestly caste - he who, regenerated and made more than a mere man by the Mysteries, incarnates simultaneously spiritual authority and temporal power, and is Pontifex Maximus, ancient dignity which Augustus had renovated. It presupposed the sense of nature as a harmonious whole permeated with invisible living forces; also a monotheism of the State through a group of “philosophers” (better say, “sages”) capable of intellectually penetrating and, to the degree it is possible, of initiatically realizing the traditional theology of the Roman world. There is an evident antithesis here in respect to the dualism of the original Christianity, with its “give to Caesar that which is Caesar’s, to God that which is God’s,” with its consequent refusal to render homage to the emperor other than as a temporal head (refusal, which judged as a manifestation of anarchy and of subversion, brought statal persecutions against the Christians).

— Julius Evola, “Emperor Julian” in Recognitions: Studies on Men and Problems from the Perspective of the Right (Arktos, 2017)

As the Ghibellines were loyal supporters of the Empire while the Guelphs upheld theocracy, in the context of the Italian Renaissance the latter took on increasingly modernist and oligarchical features, as would be most pronouncedly formulated in the figure of Machiavelli’s Prince.

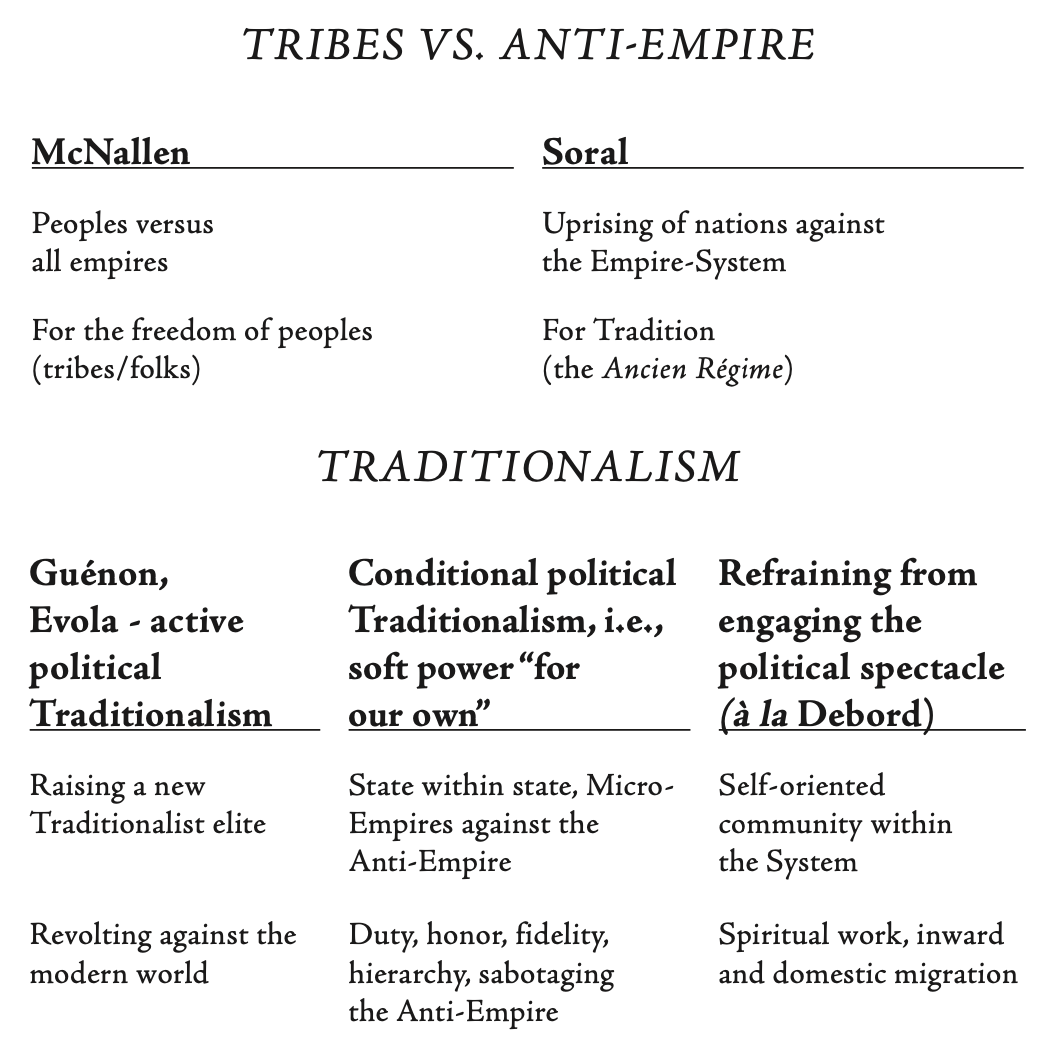

The meaning of the term “tribe” as “community” takes us from the historical context toward the contemporary situation of constructing pagan communities’ stances and relations towards the State and the modern Political overall. In this light, the question shifts to an intra-political level, and the question of “Tribes vs. Empires” already has a Traditionalist answer: communities against the Empire (the “System” à la Soral). Of importance in this response is what lies behind the word “against”, as this can conceal a whole spectrum of political strategies. Stephen McNallen argues against any Empires as such, instead standing for the format of free tribes/communities, apparently entailing democratic governance. Alain Soral’s “coming uprising of nations” is somewhat consonant with this.

A more Traditionalist strategy would be to put forth the idea of an other Empire, the real Empire against the Anti-Empire. Here, too, the path is divided. The first path is consonant with Guénon and Evola’s idea of educating a new elite in the Traditionalist worldview which, upon coming to power, would change the world in a Traditionalist vein. The second path involves the creation of hierarchical structures based on duty, honor, and loyalty within communities without fundamental political pretensions to changing their country’s governments. The first path is that of active uprising, in which pagan communities and societies are the forges of warriors and rulers, while the second path is that of creating states within states, or micro-Empires within the Anti-Empire, partially using its mechanisms and sabotaging its structures in their favor.

The latter option would mean adopting an apolitical position within the community, that is for the community to distance itself from the issues of the Anti-Empire’s profane political agenda, from its political spectacle (à la Guy Debord) in favor of spiritual work. This path comes close to the micro-Empire, but in estate terms it relates more to the priestly estate, being ascetic and monastic. Also adjacent to this would be the experience of those pagan communities and families which have migrated from large cities to the countryside and private estates out in nature.

The question of political position and activism is either secondary or of equal significance to the question of spiritual work for any pagan community or organization, and the responses to these questions are largely intertwined, condition one another, and also, as it is not hard to guess, reflect the predominant estate nature of a community’s founding circle. For a community in which the second estate is dominant, their range of rituals and practices will be martial, and participation in politics will itself be an embodiment of their inner nature and bear the character of “sacred war”, of upholding traditional and ethnic identity alongside allies against a common enemy (cf. Carl Schmitt’s Friend and Enemy distinction).

A combination of the network structure of communities in the likes of “micro-Empire within the Anti-Empire” with active political sabotage is to be found in the ideology of the English National-Anarchist Movement of Troy Southgate. Despite the eccentric name, this idea differs both from nationalism and left-wing anarchism. The essence of Southgate’s ideology lies in a decentralized network of tribes which, while existing within states, are at the same time maximally independent and are structured along traditional ethnic structures and rules. NAM is emphatically anti-globalist, anti-theocratic, and against racism, but advocates ethnic identification and structuring tribes along this line. In the latter lies the “Right” component, while the“Left” is embodied in NAM’s rejection of capitalism and in its decentralization, in the network principle similar to that of anarchistic communes. National-Anarchists do not oppose any form of statehood out of principle, but they stand against modern capitalist, liberal-democratic states and supranational globalist organizations (the UN, NATO, etc.). This is largely consonant with the positions of the Traditionalists, whose works were actively published under the auspices of resembling a movement. NAM has elected to orient itself toward paganism, especially the Germanic Tradition, as most fully corresponding to ethnic freedom and anti-capitalism and as overcoming the moral dualism of Good and Evil imposed by Christianity:

In this age of globalisation and alienation the people have in many ways been cut off from ancestral wisdom. Only by reclaiming this legacy and by reinstating it, can we open the path towards a better, more exalted and more fulfilling life. This heritage offers us an alternative cosmography, liberated from the oppressive dogmatism and moral relativism of our modern age.

As we can see, on the levels of the community, the tribe, the people, and the Empire, the structure of pagan hierarchy remains invariant, all that changes is the scale of the State and the complexity of its structure, i.e., the quantitative factor. Thus, Sacred hierarchy is maximally embodied in the Empire, and the Empire can serve as the paradigmatic model and icon of the Political on different levels and scales while invariably maintaining a just form of governance in Platonic terms.

In such a case, the problem of “tribes vs. Empires” is a question of scale or the psychological character of historical resentment on the part of the vanquished towards the victors, which reflects the base aspects of the soul that are alien to the militant Germanic tradition. On the other hand, the problem of “community vs. Anti-Empire” faces every pagan community and organization as the question of relating to the political process, towards one’s native country, and the principled position of participating in or acting outside of it.

— excerpt from Askr Svarte, Polemos II: Pagan Perspectives, translated by Jafe Arnold (PRAV Publishing, 2021).