Thinking the New Man with Romain d’Aspremont

by Andrea Falco Profili

Drawing on Romain d’Aspremont’s latest work, Andrea Falco Profili argues that the Right has become stagnant and defeatist by merely preserving what are actually past Leftist gains, and instead calls for a radical “Promethean Right” that reclaims the future through a vital, creative, pan-European vision of a “New Man.”

There is something profoundly stale in the current state of Right-wing thought. In many ways, it is an implicit defeatism and surrender. Such is the state of modern-day conservatism, which thinks in civilizational terms of no other project than its own preservation. To be clear, many of the values which it is conserving are simply old Leftist values, making the Right into a curator of ruins produced by others.

What is needed is catharsis, or more accurately, an awakening to reclaim something which has been lost: the daring spirit to imagine the future with a vitalist approach. This idea is deeply explored by Romain d’Aspremont in his essay “Penser l’Homme Nouveau” (“Thinking the New Man”), which emerges as a handbook for diagnosing the defeatist ethos of the modern Right and prescribing a new Promethean approach as a cure.

We ought to be frank: many things in the current state of affairs are beyond redemption, beyond conserving. The battle of the conservative Right is already lost: populism itself is nothing but the final reaction of a paradigm, that of “mass society”, which is clearly sunsetting; it is, in many ways, an attempt to not go gently into a “goodnight” farewell, but it hardly imagines a dawn. The diagnosis of our age has been made and remade: it is an endless recycling of lamentations about post-modernity, relativism, the loss of transcendence, and all the matters we are already accustomed to.

However, something is lacking, and that something is the force of the new. The Right has lost because it has abdicated the ambition to propose an anthropological horizon, to “think a New Man”. It has ceded to the Left the monopoly on the future, contenting itself with the role of being a brake, an eternal “party of order” that ends up ratifying the order imposed by the Left, which embodies the “party of movement”.

Real power, as d’Aspremont puts it, does not reside in the control of state or economic apparatuses. It is instead the ability to shape history in the long term, molding the dominant morality and the content of collective dreams. The Left has been a master in this. Its strength has never been coherence or realism, but its inexhaustible utopian capacity to forge models of the “New Man”.

From the new Christian man (love thy enemy, be penitent, refuse conflict) to the new man of the French Revolution (worshipping liberty and equality, embracing reason as the arbiter of morality), these same ideals became, in an exaggerated way, the ideals of the new man that communism sought to build, and then we witnessed the apotheosis of this process with the post-modern new man: stateless (“citizen of the world”), androgynous (“free from the male-female diktat”), domesticated, herbivorous, and xenophile — a being who, despising any cultural and biological determinism, believes himself capable of deconstructing and reconstructing himself endlessly.

All these models, despite their differences, originate from the same ideological roots, an impulse which can be defined as the “pole of death”: a desire for regression that takes the forms of egalitarianism, relativism, sentimentalism and hostility. In the centuries-long anthropological offensive moved by the Left, the Right has opposed nothing, instead sticking to the pathetic claim that human nature is fixed and immutable. This has been its greatest intellectual error: by acting as if human nature were an unchangeable rock, it has cultivated intellectual indolence and political inaction, while its adversaries have diligently devoted themselves to social (and soon genetic) engineering. Even if the latter achieved only 5% of their goals with each generation, they would still be incrementally and inexorably altering the dominant ideological framework, pushing history ever further to the Left.

The Right has simply become an old Left-wing party. The traditionalist reaction is a delayed acceptance of others’ progress. Conservatives bark at every “advance” of the Left, but once the new territory is conquered, they end up defending it as part of tradition. Modern conservatives grovel about the speed of change, not its direction — the perfect image of their civilization in their mind is a bonsai, something to preserve in its current shape that should never grow.

The way out of this perpetual defeat cannot be a mere tactical reorganization. It requires a philosophical revolution. The Right must make the project of a New Man its own and fill it with its own contents: elitism, thirst for struggle, self-overcoming. It must stop being reactive and become affirmative; it must, in a word, become “Promethean”. This concept is the beating heart of d’Aspremont’s philosophy. It is a dialectical reversal that seizes the enemy’s most powerful weapon and its most domesticated domain.

The future is not intrinsically Left-wing; it has simply been colonized by the Left. The conservatives’ mistake is to confuse the object (the future) with the subject that shaped it (the Left). By rejecting the future because it is associated with progressive “advances”, they condemn themselves to an eternal rearguard battle. The real struggle is not between past and future, but between a Left-wing future and a Right-wing one.

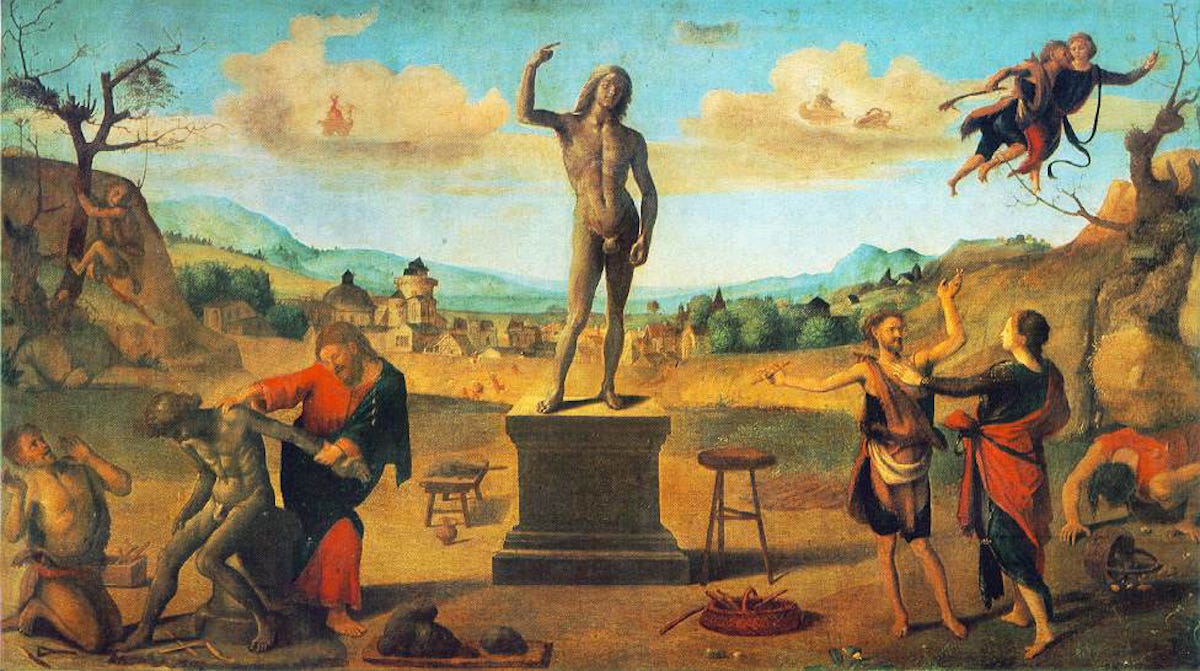

This new Promethean Right must be founded on a “vitalist morality”, which values everything that strengthens the species and fights what weakens and mutilates it. It is not about returning to an idealized past, but about projecting forward with a bold vision. D’Aspremont rightfully invokes the mythological figure of Prometheus to embody this spirit. The Right must no longer be a museum curator. Instead, it must morph into the Titan who steals fire from the gods, the archetype of rebellious creativity, the one who gives men the means to change their own nature. “Only a god can save us”, said Heidegger in our post-modern age. This god is, without a doubt, Prometheus.

This project requires a political framework equal to its ambition; it cannot be limited to man alone. Here, too, the Right is prisoner of a conservative fetish: the nation-state. Sovereigntism is the last refuge of pessimists, but it is a trench destined to be overrun. Dreaming of a return to the Europe of Nations is pure nostalgia. The new man will need the sacred, idealism, and utopia. The Europe of Nations lacks the power of the new, which is necessary to safeguard the old. The European nation-state is not an eternal given, but is the result of the fragmentation of the Roman Empire, the long-term consequence of barbarian invasions. The Europeans of the coming empire must reclaim not only the mythology of the future, but the mythology of the continental dimension which, from Augustus and Charlemagne to Charles V, Napoleon, and others has been the ambition of all great men — to reunite what has been divided.

The tragedy is not that Europe is governed by a mild and enlightened despotism, but that this despotism is radically anti-European. By one of those cunning tricks of history that Hegel spoke of, the pro-EU camp has built the institutional and administrative framework that one day could be used to impose our vision of Europe. This architecture must be conquered and reoriented. This is another one of d’Aspremont’s boldest and most astute claims. This coming Empire is not merely a geopolitical entity, it is the necessary container for the creation of the New Man.

The struggle for the future is a struggle for the character of the Transhuman. If the Right continues to demonize Transhumanism, leaving it in the hands of the Left, we will have the Transhuman and the Hermaphrodite genetically programmed according to the values of the pole of death. In other words, the Übermensch must not only be forged in character, but must also be built as a civilizational undertaking — this is what Romain d’Aspremont preaches.