The Peace Before the Peace

by Jonas Nilsson

Jonas Nilsson is a Swedish writer and documentary filmmaker. This is the sixth chapter in a series on European identity and power.

When Europeans defend the EU, they often point to the same achievement: eighty years without war between member states. No French-German conflict since 1945. Peace through integration.

It’s a powerful argument. It’s also historically illiterate.

The century before World War I — from the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to the assassination in Sarajevo in 1914 — saw ninety-nine years of general European peace. Not perfect peace. There were wars. But no continental conflagration, no conflict that consumed all the major powers simultaneously. The great powers fought limited engagements, adjusted borders, settled disputes — and stopped before the fire spread.

It was peace through balance. And it lasted longer than anything Brussels has produced.

What Historians Call the Concert of Europe

The period from 1815 to 1914 is sometimes called the Concert of Europe — a term historians use to describe the system of great power consultation that emerged after Napoleon’s defeat. But the statesmen who gathered at Vienna weren’t inventing something new. They were formalizing something much older: the European way of honest pluralism.

This is what Europe has always been. Competing powers. Shifting coalitions. Nations that knew who they were and pursued their interests openly, sometimes cooperating, sometimes fighting, but never pretending to be one.

When Gustav Vasa broke Sweden free from the Kalmar Union, the German Hansa backed him — not out of sympathy for Swedish independence, but because it served their interests. When the Thirty Years’ War threatened to destroy Central Europe, it ended not with one side’s annihilation but with the Peace of Westphalia — a negotiated settlement that accepted religious and political plurality. Coalitions formed, dissolved and reformed. This was the living game of European politics. The Congress of Vienna gave this ancient pattern a diplomatic framework. It didn’t create it. Neither did Westphalia. They recognized what had always been.

The wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon had shown what happened when one power tried to dominate the continent. Twenty-three years of warfare, millions dead, borders redrawn repeatedly. The statesmen that gathered in Vienna after the war drew a conclusion: unlimited war for unlimited aims produces unlimited destruction.

So they articulated what Europe had always done: balance of power, coalition-building, limited wars for limited objectives.

It was a shared understanding among the great powers that certain rules applied: no single power would be allowed to dominate, borders would change only through negotiation or limited war, and the great powers would consult before acting.

This system didn’t aim at preventing all conflict. It managed conflict. And that distinction matters.

The Technology of Limited War

The nineteenth century saw revolutionary changes in military technology. Railroads allowed armies to mobilize faster than ever before. The telegraph enabled real-time communication across continents. Industrialization produced weapons of unprecedented lethality. Mass conscription created armies numbered in millions rather than tens of thousands.

These changes could have made war more catastrophic. Instead, for most of the century, they made honest pluralism more effective.

Better communication meant diplomats could respond to crises faster. Railroads meant armies could mobilize and demobilize quickly. The very efficiency of industrial-age military power made it easier to achieve limited objectives and then stop.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 illustrates this. Prussia mobilized with terrifying speed, defeated France in months, extracted territorial concessions and reparations, and stopped. Paris fell, but France survived as a great power. The war was brutal but bounded. It achieved Prussian objectives — German unification, Alsace-Lorraine — without destroying the European system.

Compare this to what came later, and the contrast is stark.

Small Fires Prevent Large Ones

When I studied at the Swedish Defence University, we read Clausewitz and Moltke — the Prussian theorists who understood war as an instrument of policy, not a moral crusade.

Clausewitz’s famous dictum that war is politics by other means contains an insight that modern humanitarians miss: if war is politics, then it has political limits. You fight for objectives. When you achieve them, you stop. War without political limits becomes something else entirely — slaughter for its own sake.

Honest pluralism operated on this logic. Wars happened. The Crimean War, the Wars of Italian Unification, the Austro-Prussian War, the Franco-Prussian War. But these were limited conflicts with limited aims. They adjusted the balance of power without destroying it.

Think of it as controlled burning. Foresters deliberately set small fires to clear underbrush and prevent the accumulation of fuel that leads to catastrophic wildfires. The old European system worked similarly. Small conflicts released pressure, resolved disputes, adjusted borders — and prevented the accumulation of grievances that would eventually explode.

The alternative — suppressing all conflict, demanding perpetual peace, treating any war as unacceptable — doesn’t eliminate the underlying tensions. It just lets them build until they become uncontainable.

This is what EU enthusiasts miss when they celebrate eighty years of peace. The question isn’t whether you’ve prevented war. The question is whether you’ve prevented the conditions that produce catastrophic war. And that requires asking uncomfortable questions about what pressures are building beneath the surface.

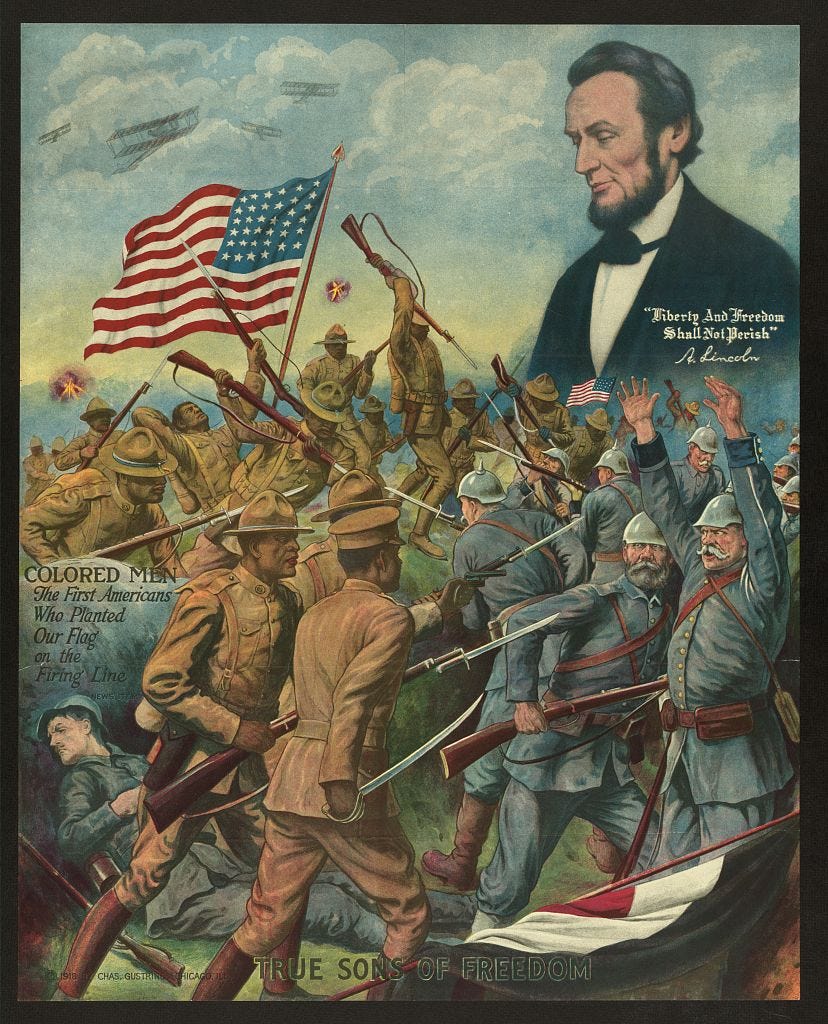

When Migration Becomes Conflict by Jonas Nilsson

Mass migration is not a social policy issue. It is a question of power.

In this collection of essays, published in English for the first time, Jonas Nilsson presents migration as a struggle over territory, sovereignty, and group survival. Liberal universalism dissolves political realities into abstractions, while real groups consolidate, compete, and harden.

From Rhodesia to South Africa and Sweden, demographic change reshapes the state from within.

Drawing on the political realism of Carl Schmitt and the strategic thought of Martin van Creveld, Nilsson presents migration as a decisive test of political order.

How Wilson Broke the System

Between 1914 and 1919, honest pluralism was destroyed. Not just the Vienna framework, but the ancient pattern itself. The destruction came in two phases.

First, the war itself spiraled beyond anything the old system was designed to handle. The July Crisis of 1914 should have produced another limited Balkan war. When the great powers mobilized, soldiers marched off expecting to be home by Christmas. A century of limited wars had taught them what war looked like: sharp, decisive, bounded. No one imagined four years of industrial slaughter.

Instead, the alliance systems pulled in all the great powers.

But even this catastrophe might have been salvaged. By 1917, all parties were exhausted. The outlines of a negotiated peace were visible — a return to something like the pre-war status quo, with adjustments. Germany had not been invaded. Paris had not fallen. Both sides had bled themselves dry, and both had reason to stop.

This is how European wars used to end. The Thirty Years’ War killed a third of Germany’s population, yet it concluded with the Peace of Westphalia — not total victory, but negotiated coexistence. The Napoleonic Wars, for all their destruction, ended the same way: a defeated France reintegrated into the European balance. World War I should have ended the same way.

Then America entered the war.

Woodrow Wilson didn’t come to restore the balance of power. He came to transcend it. He came with a vision of a world made safe for democracy, a world where the old European games of power politics would be replaced by collective security and international law. He came to end all wars by winning this one so completely that the system which produced it would be destroyed.

It was a revolution in the fundamental logic of warfare.

Under the old system, you fought for limited aims and accepted limited outcomes. You defeated your enemy’s army, extracted concessions, and made peace. Today’s enemy might be tomorrow’s ally. The balance of power made total destruction impractical — try to annihilate one, and the others would intervene.

Wilson rejected this logic entirely. Germany wasn’t just an adversary to be defeated and reintegrated. Germany was a criminal to be punished. The German system had to be destroyed, nothing less than unconditional surrender would suffice.

Versailles: Defeat Without Victory

This is the paradox of the Treaty of Versailles: it treated Germany as completely defeated while leaving Germany largely intact.

German armies had not been destroyed. Berlin had not been occupied. The German homeland was essentially untouched — no foreign soldier had set foot on German soil east of the Rhineland. Germans had experienced privation and loss, but not conquest.

Yet the treaty imposed terms appropriate to total defeat: massive territorial losses, crushing reparations, military limitations that reduced Germany to impotence, and above all, Article 231 — the War Guilt Clause, which forced Germany to accept sole responsibility for the war.

This was the worst possible combination. Germany was humiliated but not broken. Germans could see with their own eyes that their country had not been conquered.

Honest pluralism would never have produced this outcome. A negotiated peace in 1917 would have looked something like the settlement after the Franco-Prussian War: territorial adjustments, reparations, but fundamental acceptance that Germany remained a great power with legitimate interests. And everyone could carry on with their lives.

Every German who lived through the 1920s knew two things simultaneously: Germany had not really lost the war, and Germany was being punished as if it had committed a crime. This cognitive dissonance was the seedbed for everything that followed.

The American Interest

Wilson’s idealism was probably real. He might have genuinely believed he was building a better world. But idealism doesn’t preclude identity and interest. And America had interests that aligned perfectly with destroying the old European order.

Before World War I, the great powers of Europe dominated global politics. The British Empire, the French Empire, the German Reich — these were the actors that mattered. America was a rising power, but the world’s power centers were in London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna. European empires controlled most of the globe.

The war weakened all of them. The peace weakened them further. And the principles Wilson championed — self-determination, democracy, collective security — were perfectly designed to weaken them even more.

Self-determination sounds noble. Every people should have their own state. And in principle, there’s nothing here that contradicts the old European way — borders had always shifted, new nations had always emerged from old empires. That was honest pluralism in action.

But Wilson’s self-determination served a different purpose. Applied to Europe’s eastern empires, it shattered structures that had balanced power for centuries. The Austro-Hungarian Empire broke into a dozen successor states. The Ottoman Empire was carved into mandates. What emerged was a vacuum.

And vacuums get filled. The old European powers had locked up most of the world’s territory and markets. And now those locks starts to brake.

This served American interests beautifully. A Europe of competing great powers had shut America out and now space starts to open up for American expansion.

I’m not suggesting Wilson consciously designed this. He probably believed every word he said. But the alignment between American idealism and American interest is too perfect to ignore. The principles that made Wilson feel righteous also made America dominant.

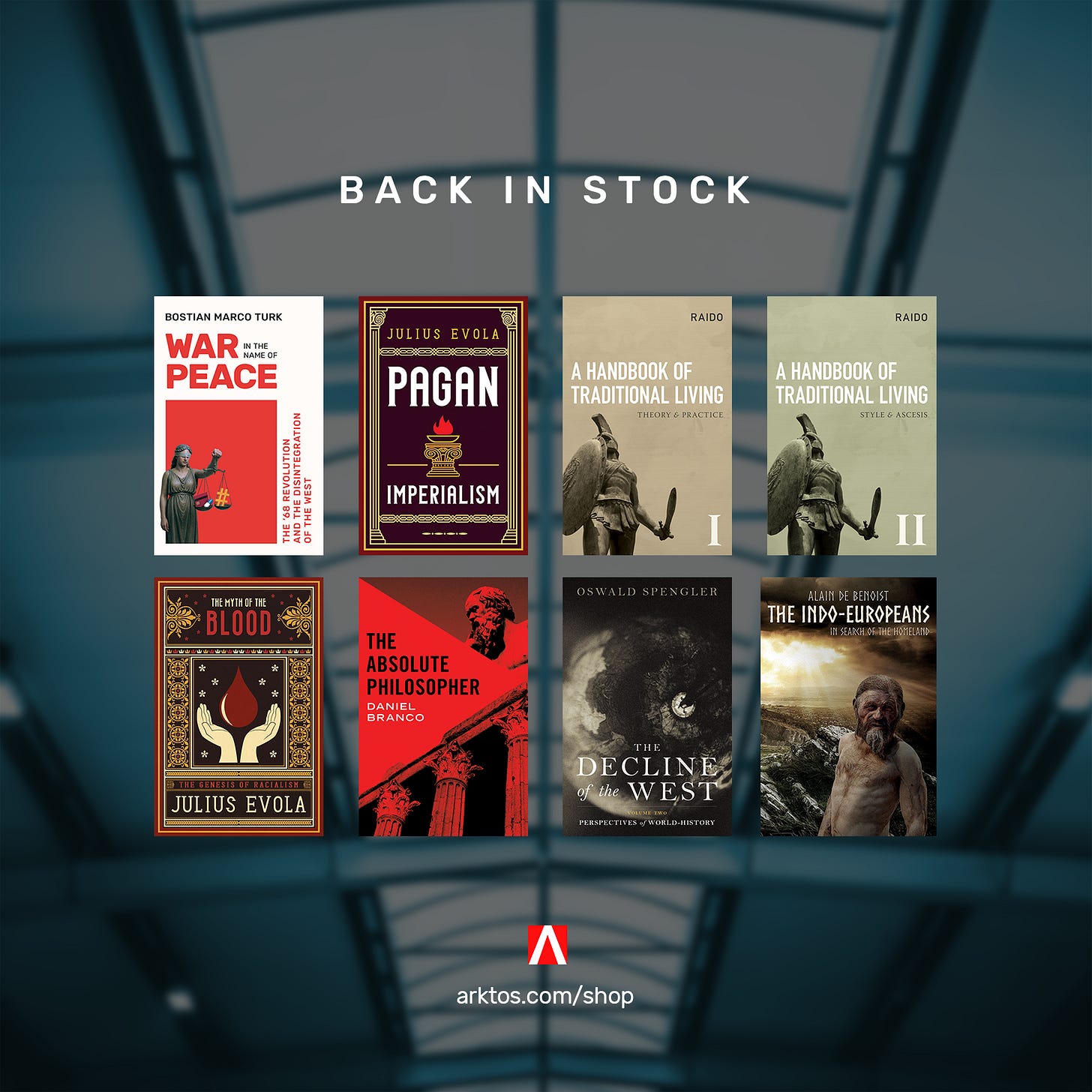

Arktos Journal survives because readers choose to sustain it. This enables us taking risks on new authors, translating neglected thinkers, and publishing work that would never make it to you through institutional or commercial frameworks.

We publish work rooted in archaic values, civilizational memory, and long-form thought, and have been doing so since 2009.

The editors do this work pro bono, driven by conviction rather than careerism. If you value independent intellectual production that is willing to publish what others will not, support this project and make its continuation possible.

Decolonization and the Opening of Space

The full implications of Wilson’s revolution didn’t become clear until after World War II, when America actively dismantled the European colonial empires.

Again, the rhetoric was idealistic. Self-determination for all peoples. The end of colonialism. Human rights. The language was impeccable.

But the effect was strategic. Every European colony that became independent was a space that opened for American influence. The British Empire’s retreat from India, from Africa, from everywhere. It was the dissolution of a closed system, a system where European powers had locked up most of the world’s territory and markets.

America didn’t need formal colonies. America needed access — access to markets, to resources, to strategic locations. The European empires blocked that access. Their dissolution removed the barriers.

The Suez Crisis of 1956 made this explicit. When Britain and France, acting like the great powers they still imagined themselves to be, tried to seize the Suez Canal, America sided with Egypt and forced them to withdraw. The message was clear: the age of European power projection was over. These former great powers would operate within boundaries set by Washington.

This is basic power politics where America used idealistic language to pursue strategic interests, just as every great power always has. The difference was that America was stronger than the European powers already tied up in this new order of institution, so American interests could prevail.

The Myth of Institutional Peace

And so we arrive at the European Union, founded on a myth.

The myth says: Europe was cursed by nationalism and power politics. We fought endless wars because we couldn’t transcend our differences. Then, after the catastrophe of World War II, we finally learned our lesson. We embraced the Wilsonian faith that institutions could replace power politics. We integrated. And those institutions gave us peace.

I see this differently.

Europe’s peace since 1945 wasn’t produced by institutions. It was produced by American hegemony, a shared enemy, and the binding of Germany. NATO’s first Secretary General, Lord Ismay, was refreshingly honest about the alliance’s purpose: to keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down. The Coal and Steel Community served that third objective — binding German industry so tightly that independent action became impossible.

The European powers didn’t stop fighting because they had transcended power politics. They stopped because they were exhausted, occupied, and constrained.

“Without the EU, we would be at war.” This is stated as obvious truth, used to silence any criticism of European integration. But it inverts the historical record. We had peace before the EU — a longer peace, maintained by different means.

Compare Paris, Berlin, London, or Stockholm today with what they were a century ago. These were the capitals of peoples who knew who they were and acted accordingly. Now they are administrative zones, increasingly unrecognizable to anyone who remembers what they were. No one in their right mind would call these cities peaceful today.

Honest pluralism allowed small fires to prevent large ones. Conflicts happened, pressures were released, and the system survived. The EU suppressed all fires by engineering dependence. The founding logic was stated openly: make nations so intertwined that war becomes impossible. Not unthinkable — impossible.

Here’s what the EU’s defenders never mention: the old system could handle conflict. It had mechanisms for managing disputes, adjusting borders, releasing pressure. The EU has no such mechanisms. It treats any conflict between members as unthinkable, which means it has no way to handle conflicts when they inevitably arise.

The pressure builds. The tensions accumulate. And the institutions designed to prevent conflict have no capacity to manage it.

Honest pluralism understood something the EU has forgotten: peace is not the absence of conflict. Peace is the successful management of conflict. And you cannot manage what you refuse to acknowledge.

The Seed That Was Planted

Versailles planted a seed.

It established that wars must end in total victory or total defeat. That enemies are criminals, not adversaries. That the goal is justice in the legal sense, as if nations were defendants in a courtroom. That peace means eliminating the sources of conflict rather than managing them.

This seed grew into World War II, which ended in the total defeat that World War I had not quite achieved. Germany was occupied. Germany was divided. Germany was forced to confront its crimes in a way that went far beyond Versailles.

And from that confrontation grew something new: a Germany that had internalized its own guilt so completely that it could never again trust itself with power. That may change — but not yet.

That story is the next chapter. But it couldn’t have happened without Versailles. Without Wilson. Without the destruction of honest pluralism and its replacement with a moralized politics that demanded total victory and accepted nothing less.

The peace before the peace was real. It worked.

Excellent analysis. However I believe wilson was not so naive when handing over the American currency to a cabal of jewish bankers in 1913! The federal reserve which isn't federal!