The New Right: The Name of Great Europe

by Daria Platonova Dugina

Daria Platonova Dugina recalls the emergence and focal points of the French Nouvelle Droite or ‘New Right’, highlighting the “Manifesto for a European Renaissance” as the essential handbook for an authentically European cultural revolution.

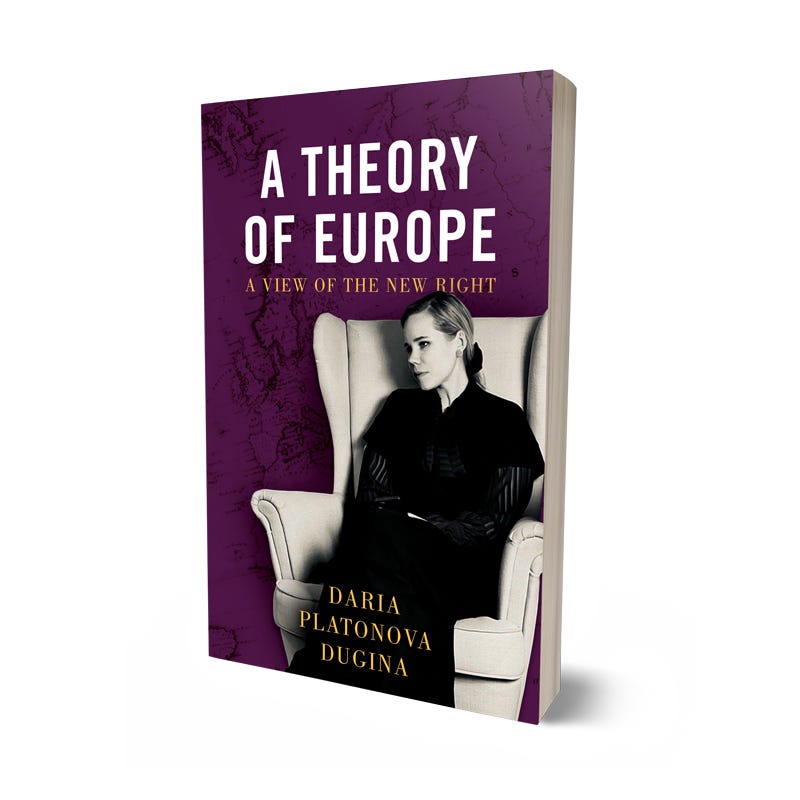

The following text — excerpted from Daria Platonova Dugina, A Theory of Europe: A View of the New Right (Arktos, 2024) — was originally written as the foreword to Posledniaia bitva za Evropu. Manifest Novykh Pravykh [The Last Battle for Europe: Manifesto of the New Right] (Moscow: Slovo, 2023), the Russian edition of Alain de Benoist and Charles Champetier’s Manifesto for a European Renaissance [English edition published by Arktos in 2012].

The Nouvelle Droite and GRECE: The Name of Great Europe

The Logos of Eternal Europe

As a movement and phenomenon, the French Nouvelle Droite represents a traditionalist, cultural, conservative revolution. The New Right might be called the new encyclopaedists or the new European “Enlightenment” — Enlightenment 2.0 — but in the reverse. If you want to know the real Europe and its high intellectual achievements, then it is necessary to get acquainted with the books of Alain de Benoist, the journals Éléments, Kris, and Nouvelle École, and the conference materials of GRECE. These works and publications are key to unveiling the real intellectual heritage of the great Europe that today is under the baton of globalist liberal hegemony, the Europe and its Tradition that are today subject to ostracism.

Reading the French New Right means discovering for yourself the deep Europe that harbours respect for man as a spiritual being, for peoples as living essences, for nature as a source of life and energy, and for tradition as a bearer of genuine knowledge preserved over the centuries. This Europe has no American recitatives, no BLM, no artificial opposition between “left” and “right”, no cultural Marxism, no Dark Enlightenment, no vulgar materialism, no globalist racism, no obsession with the economy, no liberal totalitarianism, no universal- ism, no egalitarianism, no alienated individualism. The New Right is authentic Europe. Eternal Europe.

The Emergence of the New Right: From GRECE and Nouvelle École to Éléments and Krisis

The emergence of the French New Right is generally associated with the years 1967–68, when GRECE, the Groupement de recherche et d’études pour la civilisation européenne (Research and Study Group for European Civilisation), was founded as an ensemble of intellectuals whose aim was to analyse European civilisation through the prism of philosophy, anthropology, psychology, political science, and biology, all for the sake of restoring European intellectual identity. “Give life to sinking culture!” — such was the idea and aim of this movement.

GRECE began with organising yearly thematic conferences — such as “The Cause of Peoples”, “Left-Right: The End of the System”, “The United States: A Danger”, “For a Gramscianism from the Right”, “Against Totalitarianisms—For a New Culture”, “The Failure of Disneyland”, and “Europe: A New World”—and its first conference publications were released in October 1973.

In 1968, Alain de Benoist, the leader and inspirer of the movement, founded the yearly journal Nouvelle École, the first issue of which came out in February 1968. By 1985, the journal’s print circulation reached 10,000 copies. The journal’s issues were dedicated to particular personages, such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Vilfredo Pareto, Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Knut Hamsun, Georges Dumézil, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Konrad Lorenz, and Charles Maurras. The topics included Christianity, paganism, mass culture, the Indo-Europeans, geopolitics, archaeology, political theology, language, demography, biology, psychiatry, the Conservative Revolution, the Greeks and Romans, and the philosophers of the Enlightenment.

The publication became the print organ of the new European Conservative Revolution and was distinct from all other publications of the time by virtue of its wide range of topics and personages, its conservative-revolutionary orientation, its going beyond the classical field of left and right (its issues were dedicated to right-wing as well as left-wing intellectuals), as well as its integral and interdisciplinary approach to the study of man, Europe, and Tradition (ranging from religion to zoopsychology). The editorial board of Nouvelle École included the philosopher Raymond Abellio, the journalist Louis Pauwels (who at the time was the head of the prestigious newspaper Le Figaro), the sociologist Georges Dumézil (until 1974), the philosopher Julien Freund, the zoopsychologist Konrad Lorenz, the historian of the Conservative Revolution Armin Mohler, the scholar of religion Mircea Eliade, the archaeologist and historian Marija Gimbutas, and many other of Europe’s most prominent intel- lectuals of the time.

In September 1973, the New Right released the first issue of what would become the cult journal Éléments, which is still in publication (with varying periodicity, but not less than once a month). Éléments features analysis of acute social, political and philosophical topics, such as feminism, economics, the consumer society, ecology, religious crisis, socialism, Islam, corruption, the decay of the political class, populism, globalism, censorship, bureaucracy, immigration, culture, art, gender, etc. A number of intellectuals have collaborated with the journal, such as Michel Maffesoli, Michel Onfray, Marcel Gauchet, Bernard Langlois, Pierre Manent, Patrick Buisson, Christophe Guilluy, Jacques Sapir, Jean-Yves Camus, Serge Latouche, and Jean-Claude Michéa.

The publication positions itself as “neither left nor right” and is especially critical of Western liberalism, globalism, egalitarianism, individualism, the Americanisation of France, and the consumer society. Its critiques are bound up with rethinking and reconstructing the fundamental concepts of Tradition and a “New Europe” (a “Europe of Peoples”).

In 1988, the journal Krisis saw the light of day for the first time and was announced as a “publication for ideas and debates”. Oriented to a considerable degree towards “left” audiences, the journal’s authors have included prominent left intellectuals like Costanzo Preve, Jean Baudrillard, Régis Debray, and even the left-wing politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon. The issues’ themes always pose a question: “Culture?”, “Evolution?”, “Morality”?, “Society?”, “Sexuality?, “Populism?”, “Left/ Right?”, “Paganism?”, “Progress?”, “Identity?”

A Cultural Revolution — in 1979?

Éléments began to exert tangible influence on French society and politics, and by 1979 the New Right had penetrated the media-sphere: Louis Pauwels, the chief editor of Le Figaro, offered Alain de Benoist to maintain a column entitled “Movement of Ideas”, and the conservative publications Valeurs actuelles and Le Spectacle du monde invited a number of New Right authors to collaborate with them. GRECE’s 12th congress, titled “The Illusion of Equality” and devoted to critiquing universalist human rights and the mirages of egalitarianism, was held at the Palais des congrès and gathered representatives of French and British academia (the speakers included Thierry Maulnier, a member of the French Academy of Sciences, Henri Gobard, a professor at the Vincennes Institute, and Hans Eysenck, the director of the Institute of Psychiatry of King’s College London), as well as politicians (for instance, Julien Cheverny, then a deputy of the Socialist Party). The presence of politicians from the conventional “left” political front and academicians testified to the fact that the New Right’s ideas had entered universities and political parties and now posed a threat to the liberal system.

The GRECE movement began to exert an influence not only on politics, science, and the educational sphere, but also on culture. This posed a direct challenge to liberal hegemony, one which the latter was incapable of responding to. In the preface to his book Les Idées à l’endroit (which literally means “ideas in the right place” or “the right ideas”), Alain de Benoist remarked that the New Right had effectively carried out a coup. De Benoist openly says:

“We managed to overturn and break the table of ideas and the systematisation of concepts and ideas put forth by liberalism. Thus, the New Right succeeded in getting off the plane of hegemony and began developing an autonomous pole of counter-hegemony, a pole for a new culture.”

In the summer of 1979, more than 500 articles on the New Right appeared throughout the European and American press. It was at this time that GRECE came to be called the “New Right”. For GRECE themselves, such a name was not at all correct, as the movement’s members proclaimed a complete rejection of the division into left and right, and instead saw themselves as passing onto the plane of metapolitical struggle, where the real poles are globalism and anti-globalism, universalism (egalitarianism) and multipolarity.

On 5 July 1979, journalists of the left-liberal publication Libération wrote that “la gauche est en retard d’une guerre” (“the left is late to a war”), and Le Point wrote that the left was facing catastrophic defeat. The American National Review deemed the New Right responsible for “a cultural coup d’état”, while the French ultra-globalists Bernard-Henri Lévy and Laurent Fabius promoted a proposal to ban even mentioning the New Right in order to “suffocate them by silence”. An active campaign to discredit the movement was launched: the right accused them of “abandoning right-wing economics” and “pointlessly engaging left-wing ideas”, while the left blamed them for “masking right-wing ideas under academic concepts”.

Thus, the New Right was subjected to critique from all political fronts. Behind this, of course, one can easily detect the strategy of the globalist centre itself, which combines right-wing economics with left-wing politics and uses both the right and left within the system to struggle against its main opponents. The New Right became this main opponent, because they were neither a left-wing nor right-wing flank of the existing system, but instead represented a radical opposition that combined right-wing politics with left-wing economics. In this lies the power of the Nouvelle Droite, the danger it poses to the globalists, and the explanation for the vital force of the movement that continues to flourish to this day.

Not a single argument employed by the campaign worked—neither the claim that the New Right are “apologists for totalitarianism” nor the claims that they are “right” or “left”. Instead, from this wave of criticism the movement gained a name, fame, and stronger influence. […]

The Rights of Peoples: The New Right’s Interpretation of the Foundations of Geopolitics

The New Right also revived European interest in the discipline of geopolitics, which seemed to have flickered out following the Second World War. The New Right’s attention was especially drawn to the works of Carl Schmitt. In the 44th issue of Nouvelle École, an article by the philosopher Julien Freund expounded Schmitt’s ideas in a hierarchical order that is fundamental to the thinking of the New Right. In the first place, the New Right’s attention was drawn to analysing the phenomenon of “the Political”.

“The Political” (das Politische) is the domain of social relations between diverse subjects (states, blocs, etc.) and is based on distinguishing between “friend” and “enemy”. This friend/enemy pairing lacks any personal connotations and is instead exclusively connected to the field of groups, i.e. a political enemy is the enemy of the group to which the analysing subject himself belongs. For Schmitt, politics is always a confrontation between different political units (groups and collectives of various scales) and presupposes a permanent multiplicity, which Schmitt calls the “pluriversum”. Politics exists only when there are several groups and there is opposition between them. The defining line of Schmitt’s concept is that it distinguishes the Political as a separate phenomenon that can precede the state.

Of extreme importance to the New Right is Schmitt’s interpretation that the basic principle of politics is “pluriversality”. In and of itself, the Political is universal in that the principle and confrontational dyad of friend/enemy is all-encompassing and permeates the whole world, but a multiplicity is necessary for the Political to exist. There must always be relations between political units (parties, states, movements) and the distribution of these relations in accordance with the principle of friend/enemy. The New Right critiques the universalism of globalist politics by highlighting how the West’s universalism and egalitarianism harbours the desire to impose the West’s own values on other peoples. As Alain de Benoist notes in the Manifesto for a European Renaissance:

“The Westernisation of the planet has represented an imperialist movement fed by the desire to erase all otherness by imposing on the world a supposedly superior model invariably presented as ‘progress’. Homogenising universalism is only the projection and the mask of an ethnocentrism extended over the whole planet.”

Thus, while it is actually waging struggle against its enemy, the modern West masks the pursuit of its agenda under the aegis of “establishing democracy” and “defending human rights” in various regions.

For the New Right, as indicated in the Manifesto, the main enemy is liberalism:

“In the age of globalisation, liberalism no longer pres- ents itself as an ideology, but as a global system of production and reproduction of men and commodities, supplemented by the hyper- modernism of human rights.”

Liberalism treats politics as a mere technique or technology. For the New Right, inspired as they are by the traditions of ancient Greece, which saw politics as a space of battle, as agon, it is of fundamental importance to rehabilitate politics, to de-colonise the symbolic imagination that is enslaved by commercial values. Thus, following Schmitt, the New Right understands politics as an existential phenomenon. Against human rights (which are part of the liberal, de-personified, technocratic interpretation of the Political), the New Right calls for the rights of peoples. “Defend the rights of peoples”—this slogan and call was voiced by the intellectuals of the French New Right back in 1969.

According to Alain de Benoist, the periods of the “three nomoi of the Earth” that Schmitt described have come to an end:

The first nomos was the nomos of Antiquity and the Middle Ages, wherein civilisations lived in a certain isolation from each other. At times there were attempts at imperial unification, such as the Roman Empire, the Germanic Holy Roman Empire, and the Byzantine Empire. This nomos disappeared with the onset of Modernity, when modern states and nations appeared in the period that began in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia and ended with the two world wars—this is the nomos of nation-states. The third nomos of the Earth corresponds to the bipolar regulation during the “Cold War,” when the world divided between West and East; this nomos came to an end when the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union was broken up. The question is: what will the new, fourth nomos of the Earth be? Here we arrive at the topic of the Fourth Political Theory which is to be born. This is the fourth nomos of the Earth that is trying to appear. I think, and I deeply hope, that this fourth nomos of the Earth will be the nomos of the great continental logic of Eurasia, the Eurasian continent, i.e., a nomos of struggle between continental state power and the maritime power and maritime might represented by the United States.

The logic of Eurasia is the logic of defending the “cause of peoples”. For the New Right, accordingly, geopolitics is one of the most important sources and disciplines.

It bears dwelling in particular on the geopolitical categories with which the New Right describes the European space: for them, this space is the “middle belt”, Rimland. In this respect, the European space is close in status to that of the “Third World”. It turns out that globalism and Atlanticism have colonised Europe just as the West itself once colonised the countries of the Third World. In 1986, Alain de Benoist released a book entitled Europe, Third World, One Struggle, which argues that Europe must return to its roots and traditions and throw off the universalist dictatorship. Defending the Third World means standing for non-alignment. This means abandoning the obsession with economics that is characteristic of Western ideology.

De Benoist contrasts contemporary Europe, buried under the heavy slab of economics and human rights, to a “Europe of a thousand flags” in which the pluriverse of different regional cultures can manifest themselves. For de Benoist, the model of a Eurasian Empire is extremely important, and something of its likeness should be created in the space of Europe.

Sacred Ecology

The New Right has also put the topic of ecology at the centre of attention. Continuing and developing the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss’s idea of deep ecology, the New Right proclaims the need to construct an ecological philosophy beyond the context of capitalism. The superficial ecology that liberalism promotes sees nature exclusively as a “resource”, and the main task of this ecology (of a universalist bent) is to extract as much profit as possible out of finite natural resources. Conserving nature is necessary only in order for nature to yield more resources. Such an approach is unacceptable to the New Right, as anthropocentrism and the capitalist approach destroy the world sur- rounding us and the world as an integral whole. De Benoist writes:

“Sound ecology calls us to move beyond modern anthropocentrism towards the development of a consciousness of the mutual coexistence of mankind and the cosmos. This ‘immanent transcendence’ reveals nature as a partner and not as an adversary or object.”

The deep ecology movement has pointed to how indigenous peoples do not exploit their surrounding environment and instead preserve a stable society over the course of millennia. The anti-capitalist agenda of deep ecologists, and the New Right following them, points to the danger of megalopolises as gigantic spaces of de-personified cities. In the New Right’s opinion, every city should bear its own uniqueness. Universal containers and faceless cages destroy the human being and nature. This interpretation of ecology and urban spaces is in many respects a development of German Romantic thought, which highlighted “life” as the central force: “life” is a self-sufficient ontology dictating its own logic of energy and health. The “will to life” must be allowed to come about both within us and in our surroundings.

Conclusion

Across their numerous works and publications, the New Right, the new encyclopaedists of alternative Europe, have offered assessments of all the acute topics manifest in today’s social, political, ecological, and philosophical spheres. One can find in their works an answer to virtually any topic — from pandemics to gender. The New Right’s Manifesto for a European Renaissance presents the axis and framework of their ideas, the main vectors of their struggle, and the foremost themes of their reflections and deliberations. Acquaintance with this manifesto is your acquaintance with the real Europe.

Throughout the pages of this dense and fine-tuned manifesto, you will find a definition of the precise place of our era in its historical context as well as orientations for the future. These pages awaken mind and feeling, and they provoke debates. They are roads and starting points for reflective thinking.