Spengler and the Second Religiousness

by Naif Al Bidh

Naif Al Bidh explores Oswald Spengler’s concept of civilizational cycles, examining how cultural phenomena like the “Second Religiousness” gradually emerge, with figures like Rudolf Steiner and Nikola Tesla contributing to a synthesis of science and spirituality as society grapples with the tensions between modernity and a return to nature and mysticism.

A thorough analysis of Spengler’s civilizational cycles sheds light on the distribution of a social phenomenon across the cultural fabric through time. What is evident is that a cultural phenomenon or tendency once born does not instantaneously gain wide acceptance and dominance of the collective psyche, but rather, it appears in gradually increasing waves until they eventually flood the collective consciousness of a respective culture. For instance, the rational tendencies that came to fruition at the autumn stage of Greco-Roman culture with Socrates were first seen as a threat by the dominant and more organic summer tendencies, hence why Socrates was put to death. That said, these very same tendencies, once introduced, eventually take over the culture and become the norm at the late stage of a civilization with the rise of the “Socratic man” as the archetype of this new tendency. The same could be said concerning the distribution and consolidation of the social phenomenon Spengler named the “Second Religiousness” which occurs at the last stages of all cultures.

Manifestations of this phenomenon have been apparent during the 20th and 21st centuries with the rise of the New Age movement and 1960s countercultures, and it has also found expressions in the formal religious forms of the West, namely, Christianity. Yet, even prior to the hippie generation and New Age movements, the West had already given birth to movements that were more or less precursors to these movements. However, the lack of historical awareness in a hypermodern future-oriented world leads to a lack of understanding and acknowledgment of the past, the historical, and our continuity with the past. Spengler’s methodology transcends these specific limitations concerning historical knowledge due to its affirmation of a past-present-future continuum. German historiography has been largely shaped by historicism, and in Prophet of Decline John Farrenkopf shed light on how Spengler was in a sense shaped by such traditions, notwithstanding that his approach and model are unique compared to 19th-century German professional historians and philosophers of history. Historicism is a vague term that scholars find challenging to define, yet one fitting definition would be that all phenomena are historical in a sense, and thus one can understand the essence of a sociocultural phenomenon through outlining its development across historical time.

Lebensreform, living-reform, was a social movement that emerged in Europe during the late 19th century as a result of the collective burnout and mental exhaustion from industrialized society and urbanization. Lebensreform was a call against the rising consumerism, mechanization, and globalization, and the accelerated life-style associated with modern industrial societies. It also took into consideration the ever increasing detachment from nature as a result of industrialization. Lebensreform did not have any specific political orientation as a sociocultural phenomenon and extended across the political spectrum, with groups tending towards the right and left as well as apolitical ones. Ironically, many of the tendencies that we today tie to leftist politics, such as environmentalism and vegetarianism, were adhered to by many groups that were tied to far-right elements within the political spectrum, making them essentially “right-wing hippies”. As a civilizational phenomenon, the Second Religiousness transcends the political and ideological, manifesting itself in all facets of society. Spengler lived to witness the rise and fall of the living reform movement. In Man and Technics, he predicted the continuation of the phenomenon across the West. Concerning this, he said:

But all this is changing in the last decades, in all the countries where large-scale industry is of old standing. The Faustian thought begins to be sick of machines. A weariness is spreading, a sort of pacifism of the battle with Nature. Men are returning to forms of life simpler and nearer to Nature; they are spending their time in sport instead of technical experiments. The great cities are becoming hateful to them, and they would fain get away from the pressure of soulless facts and the clear cold atmosphere of technical organization. And it is precisely the strong and creative talents that are turning away from practical problems and sciences and towards pure speculation.

Graham Hancock once described humans as a species with amnesia, which is a description that is quite fitting with the odd cycles of progress and regression that can be noticed with the Second Religiousness and social movements. The collective amnesia humans suffer does not take long to reoccur in generational cycles. For although Lebensreform was a reaction against the first wave of industrialization, modernity, as an anti-cultural force, consolidated itself further with the second wave of industrialization. By the 20th century, as older generations were replaced by newer ones in the generational cycle, modernity was quick to blind them with its immense and dynamic force, numbing society once again with the myth of progress and its vanguard — the cult of science. Yet man, although paradoxically a Promethean technical being that defies nature — the macrocosm, is also of nature, which acts as an opposing force to modernity. In the eternal dialectical clash between nature and culture-modernity, man stands at the center, whereby in phases of mechanization and material progress he yearns for a return to nature, God, and the soul. Yet, in periods of tranquil slumber in nature, he falls prey to the never-ending amnesia he suffers from and the cycle is repeated once more. Thus, the world wars and second phase of industrialization occurring simultaneously blinded the collective unconscious once more. The dynamic Faustian nature of Western culture meant that every successive phase of mechanization and atheism was more severe than the former. The result is a collective exhaustion that leads to a more severe form of spiritual reaction that is also more expansive and transformative.

The Second Religiousness was a Western social phenomenon, although Lebensreform emerged in proximity to the heart of the respective civilization, namely, Germany. The same social phenomenon did manifest itself in America with the Third Great Awakening. However, the second wave of religiousness and return to nature in the 1960s has now expanded to encompass all of the West, manifesting itself in all of Europe and the Americas with the Beat Generation, hippie counterculture and New Age movements as the “Silent Generation” of the interwar period exhausted their creative energies following the Second World War. The movement slowed down as rationalist and materialistic tendencies of the Silent or Traditionalist generation came to the forefront once more during the world wars, but the writings and teachings of mystics and intellectuals preserved the tendencies of Lebensreform and the Third Great Awakening paved the way for the revival during the post-war period in the 1950s and 60s.

As a civilizational phenomenon that transcends the political, we see mystics across the political spectrum involved in preserving the anti-modern and spiritual tendencies in their works across the interwar period. These include the works of Helena Blavatsky and the Theosophical movement, Rudolf Steiner and the anthroposophical movement, and more right-leaning nationalist mystics such as Guido von List and Adolf Lanz who have paved the way for a revival of Germanic Paganism — Ariosophy and Wotanism. On the left end of the spectrum, perhaps one of the most influential thinkers of the Lebensreform movement was the Tolstoyan anarchist Wilhelm Diefenbach, and the continuity of his teachings with the works of Gustav Gräser and Hugo Höppener that had an impact on the countercultures of the 1960s.

As Spengler argued in The Decline of the West, the artificial and rationalistic tendencies of an aging culture are eventually met by the rise of countercultures that exhibit similar characteristics in all cultures. Bohemianism and vagabondage, the rejection of conventional modes of living, were on the rise in Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries. During the second wave, it manifested itself at a global level with the rise of the hippie trail and backpacking. Vegetarianism, environmentalism, minimalism, and a return to nature as opposed to the city and urban life are all characteristics of these types of movements as reflected by their counterparts in previous cultures. The Greco-Roman Cynics exhibited similar temperaments and were also shaped by their equivalent spiritual movements and cults like the Orphics and Pythagorean cults.

The Eleusinian Mysteries, which were essentially initiation rituals in some Greek cults, also reflect the use of psychedelics and mind-altering substances, like kykeon, in order to alter one’s state of consciousness in such countercultures. The recent works of Brian Muraresku and Ammon Hillman have shed further light on the use of psychedelics in Greco-Roman mystery cults, which give us a further understanding of the Second Religiousness that had occurred in that respective culture. The Magian, or Judeo-Christian-Islamic, culture in the Middle East witnessed the emergence of Sufism with proliferation of secret esoteric groups such as the Brethren of Purity. Some elements of Nizari Muslims embedded hashish into their tradition which stayed as part of their lifestyle with the rise of the Hashashin — Assassins during the Crusades.

Spengler emphasized that cultures go through similar life-cycles, but the unique prime symbol, or ethos, of every culture leads to the manifestation of these social phenomena through different forms. The West reflected just that with the exploration of psychedelics during the countercultures of the 1960s such as LSD and psilocybin mushrooms. Another trait common with a Second Religiousness is the rise of syncretic religions, or spiritual movements, whereby the culture does not only revive primordial faith and belief-systems, such as Germanic and Celtic paganism in the West, but also absorbs spiritual forms of other neighboring cultures and fuse them with the contemporary religious forms. The extreme dynamism of the Faustian spirit has led to the rise of a severe form of syncretism in the West, whereby the Lebensreform movements, American Great Awakenings, and New Age movements absorbed elements from Hinduism, restorationist Christianity, Buddhism, Taoism, Sufism, Paganism and Native American religions. Concerning this, Spengler said:

Occultism and Spiritualism, Hindu philosophies, metaphysical inquisitiveness under Christian or pagan coloring, all of which were despised in the Darwinian period, are coming up again. It is the spirit of Rome in the Age of Augustus. Out of satiety of life, men take refuge from civilization in the more primitive parts of the earth, in vagabondage, in suicide. The flight of the born leader from the machine is beginning.

The Lebensreform movement and the 1960s countercultures have left their mark on Western culture, yet the amnesic nature of man has led to another phase of further mechanization and technological progress with a return to hyper-rational and materialistic tendencies. In Spengler’s model, however, this will also lead to another wave of Second Religiousness. To Spengler, all cultures, like all organic phenomena, are not immortal and will eventually have to face their death or fulfillment. The energetic and naive religiosity of a young culture is eventually replaced by the rationality of its growth phase. As a culture approaches its old age and realizes the reality of death, it returns to spirituality and nature once more. Furthermore, the dialectic cycles of materialism and spirituality that have been occurring in the West since the 19th century ironically necessitate one another, according to Spengler. He argued that:

Materialism would not be complete without the need of now and again easing the intellectual tension, by giving way to moods of myth, by performing rites of some sort or by enjoying the charms of the irrational, the unnatural, the repulsive and even, if need be, the merely silly…

The current technologically infused age is one of extreme intellectual tension. The exponential growth of modernity and its expansive nature has also spread this tension globally. This will undoubtedly be followed by another return to spirituality and nature, which the current mood is yearning for. Although dialectic in its form initially, the clash between the rationalists and spiritual tendencies will end up with a victory for religiousness as the West moves closer into its winter stage. This will entail a paradigm shift of significant proportions that will in essence have an effect on the many other organs of Western culture, such as the political and scientific forms. On that front, Spengler ambitiously predicted the downfall of science, which ironically occurs from within the scientific world.

In Thomas Kuhn’s revolutionary work on the history of science, namely, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, he argued that the modern understanding of science, as a linear-progressive development, was flawed and did not reflect the actual cyclical nature of scientific development. Kuhn argued that the sciences go through cycles, starting with a pre-paradigm or pre-science phase, which is characterized by a lack of consensus concerning methodology and incongruence of theories proposed. Peaking at the “normal science” period where the scientific community has consensus on an overarching paradigm, theoretical framework and methodology. In this period, the model is successful to a degree that anomalies that were once incomprehensible are clarified and thus the paradigm gains intellectual respectability. The paradigm eventually approaches a crisis period, whereby specific anomalies cannot be explained through the dominant scientific approach, and is eventually replaced by a new paradigm through a scientific revolution or paradigm shift. Kuhn’s model is compatible with Spengler’s argument concerning the 21st-century transformation of Western sciences. Spengler argued that the end of rational science will occur when it “falls upon its own sword”, and it is precisely the program of unifying the sciences, which the Logical Positivists pushed that will cause this:

The retreatment of theoretical physics, of chemistry, of mathematics as a sum of symbols — this will be definitive conquest of the mechanical world-aspect by an intuitive, once more religious, world-outlook, a last master-effort of physiognomic to break down even systematic and to absorb it, as expression and symbol, into its own domain.

The convergence of the sciences will eventually result in a paradigm shift that would reintegrate the sciences with the intuitive tendencies of the Second Religiousness. Like the countercultures that emerged during the 19th and 20th centuries, developments have occurred simultaneously that could be viewed as precursors to this scientific paradigm shift. Of these there are the works of Nikola Tesla, who was not convinced of theories of his time concerning electricity and magnetism, and argued that although a theory could accurately explain facts we should not assume that it is necessarily true. Concerning electricity, Tesla argued, “I adhere to the idea that there is a thing which we have been in the habit of calling electricity.” He suggests that this “thing” is the fabled aether — the fifth element:

What is more important, the electro-magnetic theory of light and all facts observed teach us that electric and ether phenomena are identical. The idea at once suggests itself, therefore, that electricity might be called ether.

Beyond Tesla, the works of Walter Russell also shed further light on this specific concerning the transformation and unity of the sciences in the West. His book The Secret of Light is more or less a manifesto for the new upcoming science. Russell provided a new controversial periodic chart of the elements that synthesizes all elements into a holistic union, which is a radical shift from the standard periodic table accepted by professional chemists. Russell made some radical claims, such as the notion that “all energy [travels] in waves” and that the universe consists of “waves of motion” and there “exists nothing but vibrations”. Russell argued that the unity and marriage of science and religion will pave the way for the spiritual evolution of humans in the “New Age”.

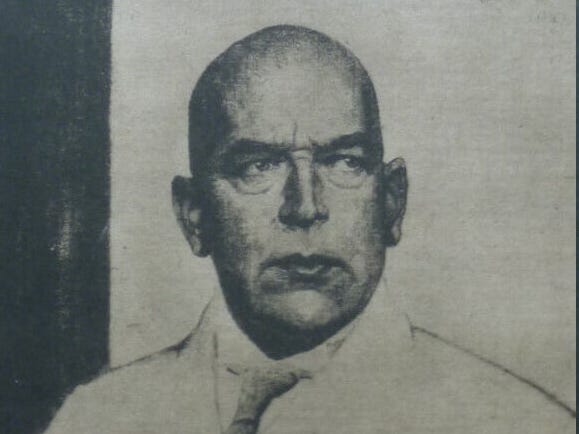

Steiner also made specific contributions on this specific front as a champion of Goethe’s conception of science — Goethean science. Spengler made a distinction between what he termed “Newtonian science” and “Goethean Science”. The former dissects in order to understand the natural phenomenon as function and is based on the causality principle and the logic of space presents them as “things-become”. The latter observes the natural phenomenon as a form rather than function and is based on “the destiny-idea” and the logic of time presents them as “things-becoming”. What Spengler is describing could be observed in Goethe’s critique, or skepticism of Newton’s color theory, as seen in his Theory of Color, which is technically based on human experience as opposed to Newton’s theoretical approach, which Goethe argued does not allow us to comprehend the phenomenon as it is. The clash between these two forms of science is also observed in the difference between Goethe’s and Darwin’s conceptions of evolution. Spengler argued that Goethe’s morphological study of “Living Nature” excluded the idea of causality, which was of course a crucial principle in Darwin’s evolutionary theory and his concept of natural selection which Spengler called a “pragmatic zoology”.

As we approach the end of what Spengler called the “materialistic world outlook, cult of science, utility and prosperity”, the separate sciences will accelerate towards one another and converge towards one conclusion and harmonious result:

The issue will be a fusion of the form-worlds, which will present on the one hand a system of numbers, functional in nature and reduced to a few ground-formulae, and on the other a small group of theories, denominators to those numerators, which in the end will be seen to be myths of the springtime in modern veils, reducible therefore — and at once of necessity reduced — to picturable and physiognomically significant characters that are the fundamentals.

This is explained in simple terms by imagining the fusion of Goethean science with Russell’s and Tesla’s works, leading to a new scientific form that is innately multidisciplinary and harmonizes all the sciences, and this harmonizing process expands to technology, and is simultaneously connected to a new emerging culture — embodied perhaps by the Second Religiousness. The results of the convergence of the sciences will finally lead to a sum of symbols, which is already apparent in the work of Steiner, Russell, and, to a certain degree, Tesla. In other words, Spengler argued that the paradigm shift will essentially find a link between the Western scientific theories and laws and the symbolism unique to Western culture during its springtime. This will lead to new concerns. Instead of asking the standard questions of the mainstream sciences, the task will be to ask why these forms emerged in Faustian Western culture, and where they have come from, and what the hidden meanings are behind these symbols and forms.

Karl Jaspers coined the term “axial age” describing the philosophical and religious revolutions that have occurred in the Eurasian world between the 8th and 3rd centuries BC, which have shaped all world religions. Jaspers described it as “an interregnum between two ages of great empire, a pause for liberty, a deep breath bringing the most lucid consciousness”. Beyond the first axial age, Jaspers also described the potential of a second axial age, which began around the 18th century and continues to this period, that would eventually pave the way for a cultural paradigm shift on a planetary scale. Steiner also introduced his own philosophy of history that is determined by higher spiritual entities — “Archai” and “Archangels”. Ironically, his own model overlaps almost perfectly with Spengler’s Decline of the West and Jaspers’ neo-axial age since he likewise argued that we are at the cusp of a new age. Steiner, however, was more optimistic than Spengler. Like Jaspers, he believed that humanity had the spiritual capacity to elevate itself to a higher level of consciousness. This is also the case with British historian Arnold Toynbee, who is sometimes viewed as the British equivalent of Spengler. After a series of challenges, and responses to these natural or social challenges, a society eventually approaches decay, which is then met with four possible responses: archaism, futurism, detachment, and transcendence. To Toynbee the first two approaches, which are proliferating quite significantly today, only hasten the decline albeit through different means; the third is also a passive acceptance of decline. Yet the last, which is connected to Spengler’s Second Religiousness, may not extend the life of a society, but could potentially sow the seeds of a new organic culture to emerge.