Rejuvenating Europe: Genesis, Doom, Futurity

by Márton Békés

Márton Békés envisions Europe as an open-ended possibility — a project of many peoples whose civilizational heritage centers West and East, North and South — but one whose fate is tragically sealed if it remains trapped in outdated frameworks instead of embracing continental horizons and staking out its own role within the emerging multipolar world order.

Europe will become an “old world” in both the literal and figurative sense if it remains trapped in the dilapidated, ill-fitting frameworks bequeathed by the twentieth century and if it fails to set out into the twenty-first by opening space for its nations to flourish and, through them, autonomously shaping its own future.

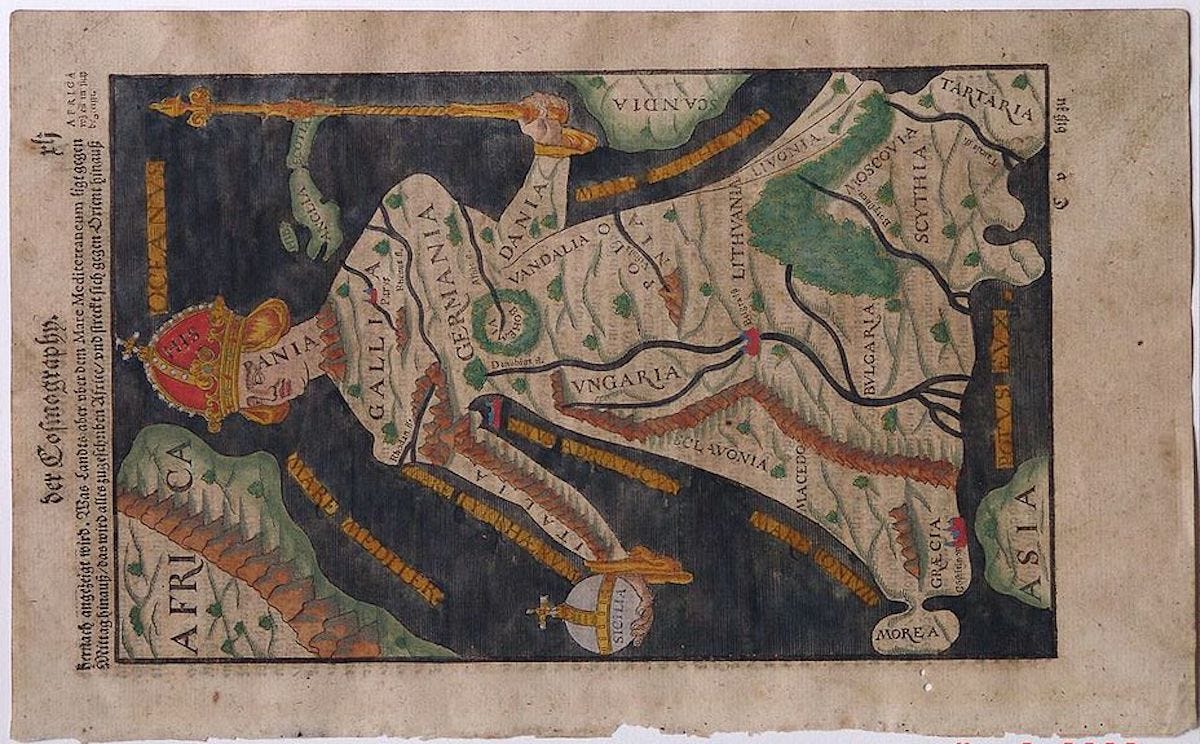

Europe is the only continent that is as much an ideal as an area defined by geography. The idea of Europe is a synthesis between East and West, North and South – just as its surface stretches from the shores of the Atlantic to the edge of the steppe and from Nordic skies to the Mediterranean sun. Europe is therefore at once the ancient and the yet-to-come; the land of conservatism and revolution, tradition and innovation, Gothicism and modernism, the archaic and the futuristic. She is as much the offspring of Apollo as of Dionysus, infused by the spirits of both Odysseus and Faust. Dynamic stability, moving equilibrium, organic construction – this is our own Europe!

The Genesis of Europe

Europe is home to a hundred indigenous peoples, most of them descended from the great Indo‑European and Eurasian tribes. In their lineage and language, as in their genetic and cultural patrimony, they include Balts, Dacians‑Thracians, Illyrians, Celts, Hellenes, Latins, Germanics, Slavs, as well as Finno‑Ugric, Turkic, and Caucasian peoples. Or they trace their origins to prehistoric populations peopling the continent before these arrivals, such as the Basques, the Etruscans, and the first settlers of Corsica, Crete, and Sicily. Since the Bronze Age – through the Iron Age and the early Middle Ages – the tribes that settled in Europe mixed with one another, absorbed neighboring ethnicities, organized themselves into communities, and set out on the path toward forming larger and ever more distinct peoples. Every modern European nation emerged historically from the fortunate crossing of multiple tribes; the Europeans are therefore all kin, a kinship consecrated by their long coexistence. Europe is equal to the great family of its indigenous peoples.

Over millennia, successive waves of migration, the struggles of settlement and state‑building, the adoption of Christianity and its division into Eastern and Western branches (and, within the latter, into further confessions), and the transformation of tribes into peoples and peoples into modern nations have fashioned Europe into a cultural, historical, and political whole of extraordinary complexity. Its hallmark is a natural plurality which, conversely, forms an organic unity. To divide it from within (through chauvinism) or to dissolve it from without (through multiculturalism) are equally grave offenses against Europe’s spirit, tradition, and heritage. Europe belongs to Europeans.

The Doom of Europe

Europe was first weakened, bled out, and irredeemably burdened by the two fratricidal world wars of the twentieth century. Then, during the half-century of the Cold War, it was occupied and partitioned by two post‑European empires: its Western half becoming an appendage of American liberalism, its Eastern half of Soviet communism. The process of Western European unification begun in the 1950s, extending in breadth and depth after the Cold War and the Central and Eastern European transitions, did not realize the ideal of a Europe of nations. Instead, it championed the project for a United States of Europe favored by local networks of globalist financial and political elites.

The deeper and tighter the Brussels integration became, the less remained of Europe’s original spirit — of the distinctive character of its nations, of member‑state self‑determination, of national sovereignty, and of the continent’s strategic autonomy. Although the European Union encompasses only about half of European countries in a narrow sense (broadly speaking, some 50 countries share Europe’s territory, of which only 27 are EU members), its political mechanism, institutional logic, and policy course inevitably shape the fate of the continent as a whole. Europe has existed for millennia; the European Union may not survive this present decade.

Over the final decade of the twentieth century – and even more over the past quarter‑century – the EU has increasingly become a centralized European federation of global liberal democracy. Over the course of this centralization, individual nations are to be melted down; the boundaries of sex, marriage, and family blurred; states consigned to oblivion; and, on top of all this, new settlers are to arrive, resulting in a kind of multicultural “open society.”

This brave new world, however, bears little resemblance to Europe’s pristine virtues. What has already been realized is more than alarming and hard to reverse. The democratic will of nations is impeded by administrative, legal, and regulatory means; freedom of speech is curtailed; tried‑and‑true institutions that undergird social cohesion (Christianity, the family, national identity, state sovereignty) are deliberately weakened; immigration from outside Europe produces ethno‑religious enclaves that can become hotbeds of crime, Islamist fundamentalism, and terror. It is increasingly evident that the so‑called “Great Replacement” is less a conspiracy theory than an actual practice.

In truth, Europe’s malaise stems from a global problem: enforced homogenization. This is not only the combined effect of globalization, technological change, capitalism, and consumerism, but the intensification of the egalitarianism born of the Enlightenment, the ultimate realization of which is especially detrimental to Europe’s native diversity – intellectually, culturally, and politically alike. The result is visible in the decline of European cinema, the demographic transformation of cities, and the spread of anglicisms. The cancelling of European culture gained impetus after World War II; the continent’s Americanization accelerated after the Cold War and, through globalization, has advanced in great strides lately compounded by alienation tied to migration. Homogenization or diversity, artificial leveling or natural plurality – that is the question of our time.

Throughout history, it was invariably the cooperation of strong European nations that produced a strong Europe. It is no surprise, then, that enfeebled nations turn out a Europe whose agenda is at once bureaucratic‑technocratic and globalist‑progressive – economically uncompetitive, technologically outdated, demographically declining, culturally stagnant, and procedurally slow, cumbersome, and paralyzed.

A further problem is that in today’s multipolar world – now visible on the twenty‑first‑century geopolitical horizon – Europe, and even more the European Union, is unable to participate with intellectual imagination and practical capacity. Having earlier subordinated itself to the United States, it now behaves like an abandoned, aggrieved lover who quarrels with everyone besides its former partner.

In the emerging multipolar order, Western civilization will be one pole among several. The question is whether Europe will be part of it – and if so, with what role. The issue is complicated by the fact that neither “Amerope” nor “Eurabia” is an option, while “Eurasia” remains an open question. The Eurocentric world order will certainly not return; yet Europe must clarify its position amid the ongoing transformation brought on by the fundamental change of the world order.

Having monopolized the definition of “Europeanness,” the EU currently lacks an independent continental vision. It tries simultaneously to defy the United States diplomatically, China economically, and Russia militarily, while its once‑strong countries cannot compete with the rising middle powers of the Global South. Nothing captures the bleakness better than the fact that the European Union, formerly a “peace project”, is buying American weapons on American credit while signing an unfavorable tariff deal with Washington.

The Futurity of Europe

Europe can be neither a continent‑wide museum nor a colony of other continents. For the rebirth of its ancient ideal, it needs a brand‑new conception – and nations whose identities remain intact even as their mutual cooperation becomes effective. For the sake of the future, we must understand that equality among peoples does not mean sameness, and European unity does not mean centralization.

Europe’s renewal springs from the force of its native ethno‑pluralism, which simultaneously leads back and propels forward – toward an ancient future. Everything is good in its proper place; one for all and all for one, as Europe’s familiar mottos put it.

Amidst the multipolarization of the world order, Europe must first rediscover its original self and then find its place in a new world order of the Großraum-based multipolarity. It would be logical for Europe to begin multipolarization at home, through harmonious cooperation among its nations. We envision a continent that realizes the Europe of peoples, nations, landscapes, and regions – where the nations of the North, South, West, East, and Center represent themselves as equals in a common forum. In this way, Europe’s traditions of empire (ancient and medieval times) and nation‑state (modernity) come into synthesis, raised to a higher plane where freedom and duty, competition and cooperation, tradition and technology presuppose one another. The synergy of Europe’s nations is its most important renewable energy.

Across natural spaces that both divide and bridge, this Europe links Eurasia via the Urals and the Caucasus; North America via the Atlantic; and Africa and the Near East via the Mediterranean. In so doing, it can help shape the world’s largest contiguous continental heartland.

Europe’s strength has always been its capacity for renewal – replenishing itself with new energies, fresh ideas, and vigorous initiatives. Europe’s renaissances, reformations, and revolutions never emerged from nothing, and they yielded positive results only when they did not lead into nothingness.

The great return – a twenty‑first‑century European ricorso – is a heroic, if realist endeavor. It does not seek to revert the Old Continent to some earlier phase (be it 1789, 1914, 1945, or 1989); in any case, this would be both impossible and undesirable.

Rather, it is the renewal of Europe from the virgin spring of its origins, so that it might live on, in the most modern forms, in accord with the unspoiled essence of its antiquity. This will be a Europe that is, in Hegel’s words, “at once the oldest and the newest.”

Economic Realities vs. Cultural Nostalgia: A Rebuttal to Békés on Europe's Decline

Márton Békés's essay presents Europe's challenges through a lens of cultural homogenization and lost identity. However, this cultural diagnosis misidentifies the disease. Europe's genuine crisis is economic and institutional, rooted in concrete policy failures rather than abstract threats to civilizational spirit.

The Real Crisis: Four Economic Failures

While Békés acknowledges that Europe has become "economically uncompetitive, technologically outdated, demographically declining, culturally stagnant, and procedurally slow, cumbersome, and paralyzed," he misdiagnoses the causes. The evidence points to four primary factors.

1. Unsustainable Welfare Spending

Public social expenditure in EU countries averages approximately 27% of GDP, compared to roughly 19% in the United States. France's public spending exceeds 57% of GDP. These resources are diverted from private capital formation, entrepreneurship, and innovation.

The consequences are measurable: between 2000 and 2020, real disposable income per capita grew by approximately 60% in the United States compared to roughly 30% in the Eurozone. Békés acknowledges Europe is "economically uncompetitive," yet attributes this to cultural homogenization rather than the structural reality that high tax burdens and generous transfer payments reduce incentives for work, entrepreneurship, and risk-taking.

2. Demographic Collapse

Total fertility rates across the EU average approximately 1.5 children per woman, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. Italy and Spain have fallen to 1.2. By 2050, the EU's working-age population will decline by tens of millions while the number of retirees explodes.

This creates impossible fiscal arithmetic: fewer workers must support more retirees through already-strained pension systems. In Italy, there will be nearly one pensioner for every worker by mid-century. Crucially, this fertility decline predates recent cultural trends and reflects economic incentives: delayed family formation due to extended education, high opportunity costs of childrearing, expensive urban housing, and welfare policies that reduce the economic necessity of children while making family formation economically burdensome through high taxes.

3. Political Ossification

European political systems have systematically excluded parties offering fundamental economic reform through "cordon sanitaire" arrangements. In Germany, established parties refuse to work with the AfD. In France, left and right unite to block the Rassemblement National. The result is political sclerosis—centrist parties share similar economic philosophies preserving the welfare state and resisting structural reform.

This consensus prevents policy innovation. By excluding parties voicing popular economic concerns, the system reinforces precisely the technocratic, unresponsive governance that Békés criticizes—but the solution is greater democratic responsiveness to economic reform demands, not retreat into cultural nationalism.

4. Guild Economies and Regulatory Capture

Europe has failed to produce a single technology company of global significance in thirty years. No European Google, Amazon, or Apple. No European company ranks among the world's top 20 by market capitalization. The reason is regulatory barriers protecting incumbents from disruption:

Uber and ride-sharing: Multiple cities banned or severely restricted Uber to protect taxi monopolies, resulting in less convenient transportation and higher costs.

Financial innovation: High compliance costs prevent fintech startups from competing with incumbent banks, who deliver inferior service at higher cost.

Artificial Intelligence: The EU's AI Act prioritizes precaution over innovation, disadvantaging European firms relative to American and Chinese competitors. European AI investment lags far behind.

Labor markets: Strict employment protection makes hiring risky and firing difficult. Youth unemployment in southern Europe regularly exceeds 30%—millions of young Europeans denied opportunity because regulations favor incumbent workers.

The cumulative effect is an economy optimized for stability and incumbent protection rather than growth and innovation. Risk-taking is penalized, capital flows to rent-seeking, and stagnation results.

The Widening Gap

GDP per capita in the United States is approximately 40% higher than in the EU. The gap is widening—in 1990, Western European and American living standards were comparable. Today, the typical American household enjoys a standard of living considered upper-middle class in much of Europe. Projections suggest this divergence will accelerate as Europe's demographic crisis intensifies and its technological lag grows.

What Békés Gets Wrong

Békés's essay contains an internal contradiction. He correctly identifies Europe's concrete failures but explains them through cultural homogenization—a diagnosis that cannot account for these failures. How does Americanization cause regulatory capture by taxi monopolies? How does immigration policy relate to the EU's failure to produce competitive technology firms? Békés provides no causal mechanism.

His vision of a "Europe of peoples, nations, landscapes, and regions" offers romantic nostalgia but no actionable solutions. Would national sovereignty reform pension systems? Would ethno-pluralism make labor markets flexible? Would regional identity reduce occupational licensing barriers? The connection is tenuous at best.

The Path Forward

If Europe wishes to reverse its decline, it must address concrete policy failures:

Welfare reform: Shift pensions from pay-as-you-go to funded models. Raise retirement ages. Make benefits sustainable. Target transfers to those genuinely unable to work.

Pro-natalist policy: Reduce tax burdens on working-age adults. Make housing affordable through supply-side reforms. Provide genuine family support rather than rhetoric.

Political responsiveness: Stop excluding parties voicing popular frustration. If voters want policy experimentation, democratic systems should accommodate rather than maintaining centrist cartels.

Embrace creative destruction: Dismantle regulatory barriers protecting incumbents. Allow new businesses to challenge old. Enable technologies to disrupt established industries. Limit professional licensing to genuine safety concerns. Make labor markets more flexible.

Conclusion

Europe's crisis is not that it has become too homogeneous or too American. It is that Europe has become too rigid, too regulated, too burdened by unsustainable commitments, and too resistant to the creative destruction that generates prosperity.

The prescription is not ethno-nationalism or continental grandiosity. It is boring, concrete reform: fiscal consolidation, regulatory liberalization, demographic policy, and political opening to reformist forces. These measures will not restore some imagined civilizational essence. But they might restore rising living standards, economic opportunity, and a future in which young Europeans need not emigrate to find prosperity.

Europe's real choice is not between homogeneity and diversity, or between Americanization and authentic identity. It is between reform and decline. The longer Europe delays confronting its genuine problems with genuine solutions, the wider the gap with more dynamic economies will grow—and the bleaker the future for ordinary Europeans.

Excuse me, but this article seems increadibly vague in regards of what sort of tangible co-operation there should be between European nations.