Our Founding Poems

by Dominique Venner

In Samurai of the West — coming soon from Arktos — Dominique Venner argues that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey form the spiritual foundation of European civilization, offering timeless answers to fundamental questions and shaping the ideals, philosophy, and identity of the West from antiquity to the present.

How do the Homeric poems concern us, we French and Europeans of the 21st century? The answer is self-evident. These poems are the foundation of European civilization, as well as of our literature and a significant part of our imagination. Within the same culture, human nature changes little, regardless of the magnitude of historical or social transformations. The fundamental questions remain the same: Who am I? What are we? Where are we going? To these questions, Homer has provided us with answers that remain valid, and he is the only one to do so with such depth. The more we are subjected to troubles caused by the incessant changes of technological domination, lifestyles, and philosophical and religious novelties, the more we need continuity and permanence—the more we need Homer .

“The world is born, Homer sings! He is the bird of this dawn...” The visionary in Victor Hugo was not mistaken in associating Homer with the radiant dawn of our world.

By Plato’s own admission, Homer was the educator of ancient Greece, and therefore ours by way of spiritual inheritance and distant kinship. To Europeans who question themselves and their identity, the two great poems hold up a mirror in which to rediscover their true inner face, cleansed of what has disfigured them and often makes them wander, anxious and lost. Like Schliemann, the persistent discoverer of the site of Troy, if one digs beneath the strata accumulated by time, it is in the meditations of Homer that one rediscovers in vigorous freshness the soul of Europe, which merges with the spirit of the Iliad.

For Aristotle, who placed him at the summit of all literature, Homer was already the primary source of thought and life. In the 3rd century of our era, Plotinus and the Neoplatonists went so far as to deify Homer. They saw in him the direct contemplator of intelligible Beauty. At the beginning of The Peloponnesian War, Thucydides refers to the Iliad as an outline of the ancient history of the Greeks, thus recognizing Homer’s merit in having laid the foundations of historical narrative. But this merit was little compared to all the others. Inspired by the gods and poetry, which are one and the same, Homer gave the Greeks and Europeans the founding books to which they could always refer in order to find themselves again.

Despite the succession of immense historical upheavals, the poet was still celebrated by the Palatine Academy under Charlemagne and during the Middle Ages. He was later celebrated by Dante in The Divine Comedy and by Petrarch, who had the poems translated into Latin. And Montaigne saw in Homer “the most perfect master in the knowledge of all things,” which was repeated by Goethe, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Camus, Joyce and so many other contemporaries.

In 2007, the National Library of France (BNF) organized an exceptional exhibition entitled “Homer: In the Footsteps of Odysseus.” The curators asked Jacqueline de Romilly to write a preface for their catalog. The great Hellenist concluded her remarks thus: “My master, Louis Bodin, a great specialist in Thucydides, told me shortly before his death: ‘Now, for me, there is only Homer.’ And it’s a bit the same for me, now; one returns to the essential, to the absolutely pure.”

With different words, this is also what the philosopher and Sinologist François Jullien says, known for his comparative work between European and Chinese thought: “When I was in khâgne,” he confides, “my friend and I were called the Homerists—we read Homer in Greek like an open book... I have always had the feeling that there was something more crucial in these first lineaments of human thought than in the philosophy that was subsequently constructed and made explicit. And ever since I have been confronting these questions, I have become more and more convinced that, if one seeks the decisive categories of European thought (“the categories of action” as well as “the categories of knowledge”), it is in Homer that one must do so, well before Plato... Read [the Iliad and Odyssey] and you will obtain the decisive orientations of Greek philosophy.”

But Homer did not speak only for the Greeks. With a perfection of form not found elsewhere, he was the Greek expression of a conception of the world common to all Europeans, whether of Latin, Celtic, Slavic, or Germanic stock. This is what the work of Émile Benveniste and his disciple, Georges Dumézil, a great reader of Homer, has clearly shown. By comparing languages and myths, the two scholars have recognized the spiritual kinship of the Indo-Europeans, the common ancestors of the peoples of historical epochs.

Stunningly, while so many famous ancient works have disappeared, victims of sackings and centuries, Homer has triumphed over time and all disasters to reach us in entirety…

Composed around the 9th century before our era, thus 30 centuries ago, the Iliad and the Odyssey describe a civilization and heroes much more ancient still. These sacred poems tell us what we were in our dawn, like no others. Under the artifices of epic legend, they are rooted in a real history and in characters who, for the most part, existed. They give account of the distant and forgotten history of all other Europeans, Celts, Slavs, Germans or Scandinavians, whose great legends offer constant analogies with the representation of the world revealed by the Iliad and the Odyssey.

The two poems translate the originality of our being in the world, our way of being men and women, before life, death, childbirth, the city, destiny—in other words, the content and meaning of our existence . They place before us an ideal of life that has shaped our better part. By narrating the trials and passions of very distant ancestors through close kinship, they tell us that our anxieties, our hopes, our sorrows, and our joys have already been lived by our predecessors, who were also young, ardent sometimes to the point of madness, yet still wise and prudent. We are told of Achilles yielding to the impetuosity of impetuous blood; Priam weeping the death of his son; Helen the bewitched; Andromache, young wife and anxious young mother; Hector the valiant; Odysseus the cunning; Penelope, skillful and faithful; Nestor the wise; Telemachus the troubled adolescent... This proximity, despite the time elapsed, awakens the idea that we eternally pursue the same exceptional adventure in a world that is both beautiful and disturbing. The history of the heroes speaks to us of feelings and behaviors that are familiar to us, very different from those suggested by the most beautiful tales of Asia or the Orient. It speaks of respect for ancestors, communion with nature, stoic courage before the inevitable, attraction to what is noble and beautiful, contempt for baseness and ugliness. Full of pity for the often cruel fate of his heroes, Homer also expresses his admiration for them.

In the Iliad, the poet shows the lucid energy of men grappling with their destiny, devoid of illusion about the gods known for being subject to their whims, and hoping for no other resource than them- selves and the strength of their soul. He shows them facing the mysterious powers of nature and their nature. Despite the omnipresence of divinities, the poet does not hold a religious or philosophical discourse. And yet, from his poem one can draw both a philosophy and a religiosity, as the Greeks did for as long as Hellas lived. Dostoevsky had understood this: “In the Iliad, Homer gave the ancient world an organization of spiritual life and terrestrial life just as strong as Christ gave to the new world.”

Forming themselves through Homer’s school, whose work embodied their spirit, the Greeks showed themselves to be great inventors of myths with unlimited meanings. But they were little interested in cosmogonic speculations. They preferred the finite to the infinite, the measurable to the immeasurable. Their preferred hero was Odysseus, who added to courage a logical and inventive spirit, manifested among other things by the ruse of the Trojan horse (Odyssey VIII, 492–516) . Was he not the protégé of Athena, the goddess whose philosophical symbol is the owl, the bird that sees in the darkness? The Greeks’ way of thinking pushed them to seek rational explanations for phenomena, and to count only on themselves to understand the universe. Attentive observation of the cosmos thus led them to distinguish visible phenomena from the invisible causes that govern them.

Thales of Miletus became the founder of mathematics by replacing the empirical approach of the Egyptians and Babylonians with a true science . In his Descriptions of the Earth, Hecataeus of Miletus became the first geographer. Xenophanes of Colophon and Pythagoras of Samos brought new materials to philosophical reflection by integrating geometry, arithmetic, and astronomy. Subsequently, Heraclitus of Ephesus was the laconic theorist of the harmony of opposites and the eternal return of life under changing forms. Later still, Democritus illuminated the atomic structure of matter, Euclid confirmed the foundations of geometry, while Aristarchus of Samos posited the hypothesis that the Earth is a planet that revolves around its axis and turns around the Sun. In a completely different register, Herodotus invented historical inquiry based on facts, Hippocrates laid the foundations of experimental medicine, Socrates and Plato imagined the infinite possibilities of philosophical questioning, Aristotle fixed the rules of logical thought, while Aeschylus and Sophocles transposed into their theater the very spirit of tragedy. These epochs saw Praxiteles and Phidias bring forth from marble the splendor of ideal human forms which one will not find at any other latitude.

These immense creations that Greek genius has bequeathed to us were contained in germ in the Iliad and the Odyssey. The two poems place the admiring observation of nature and the individuality of characters at the center of the narrative, to such an extent that one does not find in the tradition of any other civilization. None of the crushing divinities that are so frequent in the Orient or Asia imposes on them an arbitrary moral law under the threat of horrible punishments. In their very excesses, Homer’s characters are never judged according to the abstract categories of an absolute moral good or evil, but rather according to what is noble, generous, equitable, or unworthy and base. The recognition of rooted individuality permeates the two poems. It was inscribed in statuary from the classical period. It irrigated political institutions, law, and the idea one forms of the freedom of the city, privilege of noble natures, and not the claims of helots.

By composing the Iliad, a narrative based on historical reality, as proven by the archaeological research of Heinrich Schliemann and his successors, Homer became the depository of the very ancient memory of the Achaean times that preceded him by several centuries. Subsequently, despite contrary influences, the spirit of the Iliad would never dry up. It was intimately associated with Memory, the Mnemosyne divinized by the Greeks. The poet, enlightened by the Muses, daughters of Memory, is the one who knows, remembers, and transmits.

For more than ten centuries, Homer was the educator of ancient Greece, much more than the philosophers who sometimes misunderstood him. He taught everything—courage as well as the mêtis so prized by Athena, in other words, practical intelligence, cunning, feints, stratagems, in which Odysseus was so prodigal for the better.

Homer does not explain as the philosophers will; rather, he shows living examples, teaching the qualities that make a man an agathos, noble and accomplished. “Always be the best,” says Peleus to his son Achilles, “prevail over all others” (Iliad VI, 208), a notion to which I will return. To be beautiful and brave for a man, gentle, loving, and faithful for a woman, which excludes neither audacity nor valor. The poet has bequeathed in condensed form what ancient Greece subsequently offered to posterity: respect for sacred nature, excellence as a life ideal, beauty as horizon.

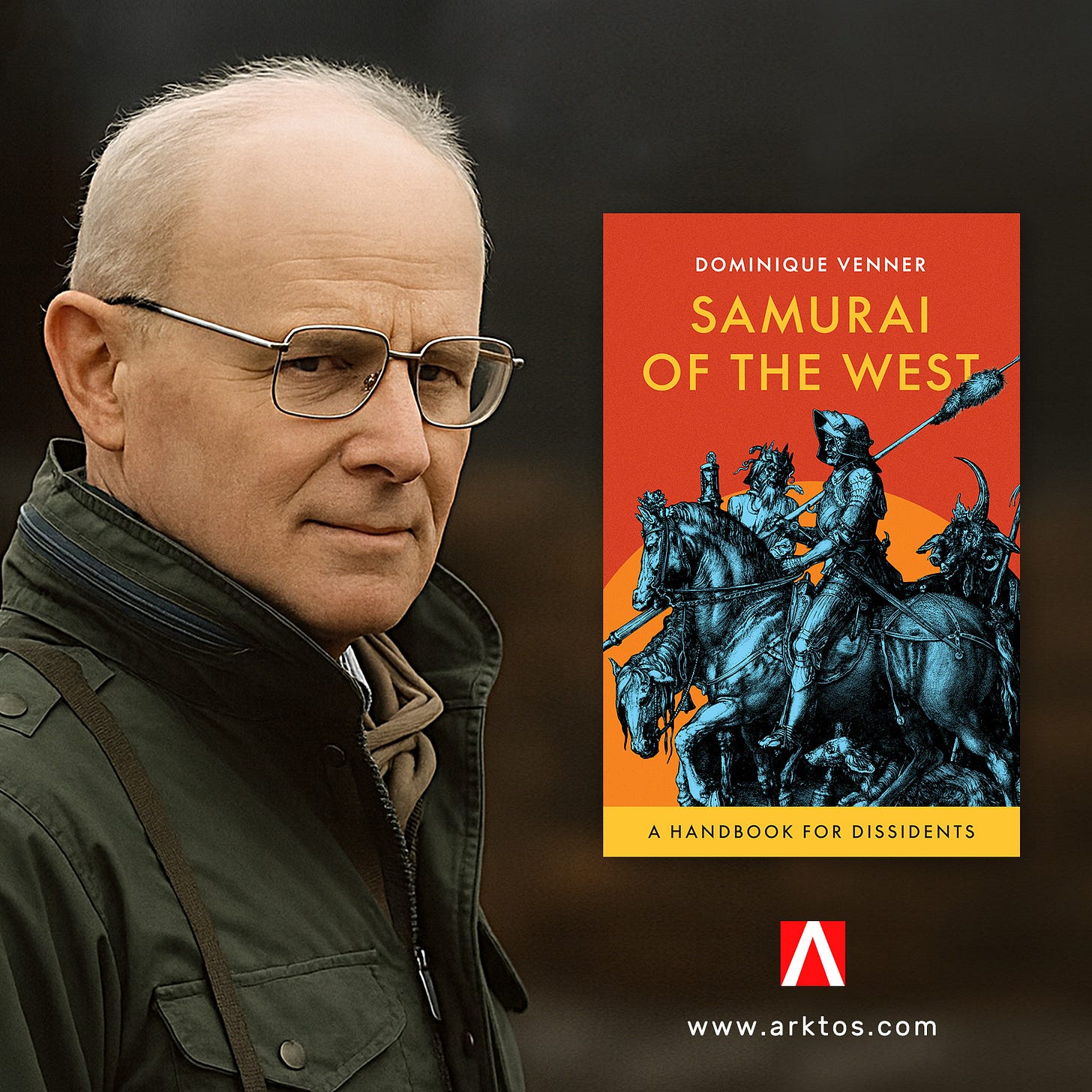

The above is an excerpt from Dominique Venner’s legendary last testament, Samurai of the West: A Handbook for Dissidents, coming soon from Arktos:

What, in your view, are the best English translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey?