On Power and Change: Elite Theory Isn't the Full Picture

by Sebastian Sköld

Sebastian Sköld argues that Complexity Theory is crucial for the dissident right to understand and effect societal change, overcoming the simplicities of Elite Theory and harnessing the knowledge of how emergent complex systems reach critical turning points.

Reality has become increasingly hard to interpret in the last few years. For instance, when moving around in Stockholm, I simply don’t know what I’m looking at anymore. Blurry images come to mind of foreigners driving around in all directions on bright pink scooters, of repugnant expressions in advertisements; I recall Swedish faces with a distant sense of confusion written all over them. I wonder why this is happening to my people. The confusing nature of the modern world makes it so that there are no simple explanations anymore, at least none that are sufficient.

On the dissident right, there is this broadly accepted idea that the problems we face are caused by groups of organized elites in finance, culture, academia, politics, etc. Many base this line of thinking on the Pareto distribution, also referred to as the “80–20 Rule,” which is a probabilistic power-law distribution that helps illustrate how things like power, resources, wealth, and so on are distributed disproportionately in small communities, corporations, populations, etc.

This model was developed some 130 years ago, and quite a lot has happened since. One problem with the model is that it can only observe patterns, not explain them. And here is where a problematic division on the dissident right lies: namely, in the speculative interpretations of, and complementary theories to, the Pareto distribution. The purpose of this article is to try and bring clarity and nuance to this division, as well as to argue against linear thinking in general, by drawing on alternative explanatory models from the perspective of Complexity Theory.

First, we have to ask ourselves why the Pareto distribution even emerges to begin with. Consistently, throughout time and history, similar hierarchical patterns emerge over and over again — why? The simplest answer to this question is: elites are needed. I say this before constructing any real argumentation because I know from experience that many who are of the persuasion that elites run the world in a top down linear fashion often view the required vocabulary to argue against such top down elitism as being part of a subversive word salad.

On the dissident right, it’s not uncommon to hear that the elites have an unfair competitive advantage over the masses because they have the ability to organize themselves in ways that are impossible for large groups of people. It’s also not uncommon to read that the elites are driven by malice, hatred, ethnocentrism, greed, etc. Some of these things may be true in part, but none of them could be true if it weren’t for the fact that the role of the elites served a function on a much broader scale; otherwise, it’s highly improbable that the Pareto distribution would emerge on such a consistent basis in different places and in different times through out history. There seems to be a much more mathematical motivation for the emergence of the Pareto distribution, rather than a malicious one.

The fact of the matter is that we’ve seen many groups of highly intelligent right-wingers try to form elitist circles since 1945, but they’ve all failed at obtaining any form of cultural, economic, or political power — why? The short answer is that there hasn’t been a need for them. On this point, many will make counter-arguments about sabotage by intelligence services, crackdown by established elites, smear campaigns, etc. Admittedly, many of these arguments may be true in part, but it’s highly improbable that every failure of right-wing organization was caused by such means, because right-wing organization has failed over a period of many decades; it’s been tried by many different groups of people and in different places. If, on the other hand, there had been a strong demand for right-wing elites in the system, then we would, without a doubt, have seen quite a few successful groups of right-wing elites, despite sabotages, crackdowns, and smear campaigns, because that would’ve been the most probable outcome.

Probability theory is one of the deadliest weapons in the dissident right’s arsenal when it comes to defeating opponents to the left of Tommy Robinson in argumentation. At the same time, however, the dissident right is sometimes afraid of some of the harsh truths which are hinted at by that very deadly weapon. One such harsh truth, I think, is that our Civilization has not been plagued by foreign usury against our will; rather, I think we’ve developed an evolutionary dependency on that foreign usury, and the emergence of the Hanseatic League is a great example of this.

Prior to the Hanseatic League, there were basically zero foreign money lenders living in northern Europe, but at some point, as we kept on trading goods and services, the need for a different level of finance began to emerge, thus enabling the existence of the money lender in northern Europe. And the more foreign the money lender was, the better, because if the money lender had been native to northern Europe, there would’ve been no trust in the trade network. This is because armed conflict within the Hanseatic League was common. It’s self-explanatory that opposing sides of a war won’t lend out money to the other side, nor would anyone want to have any debts to the other side. This is what one needs to keep in mind when one reads about how the money lenders have consistently funded both sides of the same war in European history. The foreign nature of the money lender was precisely what gave sufficient confidence to the European monarchies in order to borrow large sums of money. This is basically a short explanation as to why the federal reserve is a privately owned bank. If, on the other hand, the fed was owned by the American people, the worldwide dollar system would have zero trust, and thus the power of America would perish. America is dependent on this parasite. This is how a role emerges, and how its existence is reinforced through positive feedback between different layers of complexity.

This is why one can’t just clear them out, but even if one succeeded in doing so, new elites would quickly fill that empty void, and things would be just as bad as before, because that is what the system wants. This is a foundational cornerstone in how one needs to think when interpreting all that which is repugnant, dysfunctional, and chaotic in our modern society.

Roles are emergent. This is a profoundly thought-provoking phrase, because there are so many implications to be extrapolated from it. In most systems, both in complicated predictable systems and in complex emergent systems, this phrase has truth to it.

Here, it is necessary to distinguish between complicated systems and complex systems.

A few examples of complicated systems are: aeroplanes, electrical systems, weapon systems, etc. These kind of systems have been engineered by intelligent European men, and these systems can be understood from the top down using analysis. You can pick the whole system apart and understand it by analyzing the component parts of the system, and you can understand how the configuration of the parts give rise to some emergent property which has far greater value than the sum of the component parts. Configuration is key here, if in a firearm for instance, you swap places between the barrel and the butt-stock, the firearm property will vanish, but if you then swap the parts back together, the firearm property will emerge. There is an incredibly large number of possible combinations for component parts in these kind of systems, but there can only be one single optimal configuration. This makes complicated systems difficult, but not impossible to understand using analysis. But, on the contrary, a complex system can never be fully understood — it can’t be sufficiently analyzed, you can’t use reductionism to interpret it, and this distinction between a complicated system and a complex system is key.

Complexity and complex systems are all around us. For instance, in one biological organism, in the body, there is an unbelievably high degree of complexity between, for instance, bacterial systems, molecular systems, the immune system, the nervous system, different organs, etc. These component parts have not been engineered by someone, like in a complicated system, but rather have emerged and self-organized over a long period of time in a process which is not yet fully understood. Consciousness is, as argued by many, the most complex system we know of, and it, in turn, is dependent on the existence of many underlying physiological complex systems for its emergence. Consciousness is something which can then feed back downwards in the unified system as a form of top down control in order to regulate it.

There are many similarities between this and what’s going on in society at large. Society can be viewed as an emergent physiological phenomena. For instance, academia, culture, politics, the economy, etc, are all complex emergent phenomenologies that have in turn enabled the emergence of one single unifying consensus algorithm that now has the power to regulate some of its underlying dependencies through top down control. However, it is critical to not think about this as an elite phenomena in isolation. Top down control, yes, the Pareto distribution, yes, but only because the phenomenon has been emergent from the bottom up – and the thing which feeds back between these layers is called complexity. Therefore, one must abstain from reductionist thinking (like one would with a complicated system), because it’s useless at best and detrimental at worst. This is definitely easier said than done, especially if one is hardwired to think analytically.

On the dissident right, the “INTJ” (“Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, and Judging”) personality type is the most common. This is the quintessential engineer personality, which is very well suited for building and understanding complicated systems. This is the type of man who is behind most of the genius underpinning European technology, but being an “INTJ” comes with many drawbacks. One of them is the tendency to think analytically even when the problem in question may be strictly impossible to analyze — this may cause one to go totally insane. Thinking has, in many ways, become a maladaptive trait in our modern world.

Thinking that a different CEO would’ve done better, or that some other prime minister would’ve done better, are examples of useless thinking in relation to complexity, because even if it’s theoretically possible that the personal characteristics of a leader may have an effect on his functionality as a role, it’s still more probable that it’s the underlying dependencies of that role which will decide whether the system is functional or not; it’s not the person that’s in charge, and this is what’s underpinning the unaccountability crisis. On the other hand, reductionist thinking becomes detrimental, for instance when one critically observes a role which one dislikes, and then attributes intentionality to the person filling that role, when, in fact, there is none. This may lead one to believe that European women are inherently evil, or that underpinning the Pareto distribution lies a 2,000-year-old plot against White man. This is the type of thinking that’s going to send one down into the abyss, isolated, and forgotten; that’s why it’s detrimental.

Most people simply don’t know how they know what they know, or how to think, or why they think they know what they know. This has always been the case since the emergence of agriculture, but especially in the last few decades, thinking has become harder than ever before, even among scholars and academics. The rampant acceleration of societal complexity is making it increasingly difficult to obtain epistemic certainty when doing studies or investigations. A great example of this is what’s known as the replication crisis in science and academia, which, in a 2024 article by the Northwestern Institute for Policy Research (IPR) was described as: “In its most basic sense, the replication crisis refers to a pattern of scientists being unable to obtain the same results previous investigators found. At its most expansive, the crisis threatens the scientific enterprise itself, leading to questions not just about research practices and methods, but the very reliability of scientific results”.

Psychology, economics, and political science are especially exposed to this problem and are therefore deemed by many as being fundamentally pseudo-scientific. At the heart of this issue lies the failure to distinguish between complicated systems and emergent complex systems. The gold standard in science is still, to this day, the scientific method, but how could that method ever be reliable if the thing that’s measured is constantly changing, evolving and adapting, like how a mind, an economy, or a political system does? The scientific method is only trustworthy when experiments can be done reliably, and results reproduced with certainty; like when different labs from all over the world, irrespective of cultural or political bias, are able to produce the same results from experiments in fields such as chemistry or physics. Most fields in science and academia don’t have this property, and are therefore useless to a degree, and quite fraudulent even, since they demand funding from the working man but are unable to generate value.

There seems to exist a thick fog of confusion plaguing our Civilization, against which Complexity Theory is emerging as an alternative epistemic framework; and this, again, is how a role emerges: because it’s needed.

With the uncertainty of modern science and academia in mind, how could one expect to find better epistemic value from a piece of right-wing literature from a hundred years ago, compared to modern writing? At the very least, modern political scientists and analysts have access to huge sets of fresh data, but despite this, they still don’t know what’s going on. Quoting a thinker like Carl Schmitt as a credible source when trying to explain how politics works in the current year is a major problem, because it implies that there’s some sort of perennial value to knowledge, when in reality, knowledge goes out of date as the environment changes. For instance, to say that Schmitt’s distinction between friend and enemy plays a central role in modern politics is quite misleading. The fact of the matter is that we spend most of our time and energy fighting friend on friend, and leftist influencers and content creators are notorious for this behavior. Competition for shared resources, in the form of status, clicks, donations, attention, etc., plays a central role in this phenomena. Most of this infighting takes place in the online environment of politics, but even in traditional party politics, friend on friend conflict is becoming increasingly common, especially since the much appreciated introduction of women to politics, who are often prepared to go to any lengths in order to get media attention, whether that’s throwing a friend under the bus or making a pact with an enemy.

Our modern political landscape is of a completely a different world compared to the one Schmitt wrote about. If you’re a politician, a political influencer, or content creator, you spend just as much time being worried about what’s emerging on your own side of politics as you are of what’s emerging on the opposite side. Even though violence will rarely be received from your own side, humiliation, competition, and loss of income certainly will. Some may say that this has always been the case in politics, but that’s not entirely true because politicians from, say, a hundred years ago, were often financially independent or at the very least quite well off. There certainly used to be competition within a party, but not to the extent that we see today, because back then, women were absent, information moved slower, men were more intelligent and sensible, and there was little reason to fight over shared resources since they were all well off. Compare this to the modern dissident right for instance, where most of the public figures are dependent on funding by the crowd; in this environment, it’s only natural that purity spiraling and infighting becomes normal.

On a positive note, the change we want to see in our societies, is becoming increasingly probable with time, but that’s not because of the intentional actions of the dissident right. Rather, change is becoming more probable because of what’s going on in the system. As previously stated, roles are emergent, and this is a huge white pill, because it means that a power shift is inevitable; not from the top down, nor from the bottom up, but rather, from above and below at the exact same time as the critical conditions in the system become such that the role for right-wing elites emerges — that’s when power may be achieved, if sufficient competency is available, that is. No group of elites could have ever stopped the American revolution, or the French, nor the Russian, because all of the elites in those systems served roles which were no longer functional, those roles had de-merged; this is mathematical, not ideological — this is the lens through which one must look at history.

As our societies become increasingly less and less European, sophisticated systems will gradually become more and more dysfunctional. This has already begun and it will get worse. In time, this will cause the system to want to reconfigurate into a new state, which many people will be in favor of, and many will be against, but the reconfiguration will happen because that’s what the system is going to want, despite what the current elites may think about it. The Second Law of Thermodynamics makes this outcome probable because our society is an open system, which means that the system imports energy and it exports entropy, and if the amount of energy entering the system exceeds the amount of exported entropy by the system, the system begins to drift away from equilibrium, leading to instability.

Our society ticks all of these boxes. This instability is a prerequisite for systems reconfigurations where new forms of order may emerge from disorder, and this goes much faster than the time it took for sufficient instability to accumulate. So if it took our Civilization 80 years to reach this unstable point, it won’t take another 80 years to reach a new order; this, by the way, is not wishful thinking, this is just how open systems work, it’s coded into natural law. To help illustrate this process, it’s necessary to look at the importance of criticality in the changing of systems.

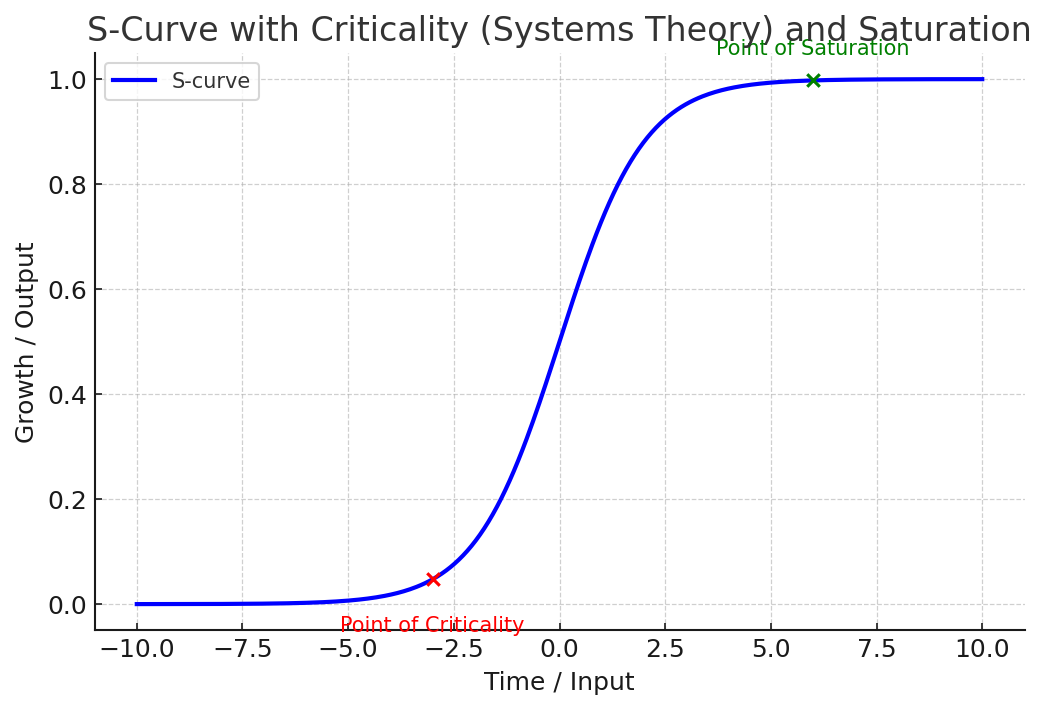

Looking at S-curves in graphs is very useful when one thinks about change in systems. If we imagine time on the X axis, and change on the Y axis; at first, Y increases slowly with X, but after a while, Y begins to increase exponentially compared to X, and after a short while, Y starts to increase slowly with X again. If you draw this graph it kind of looks like an S. This pattern reoccurs everywhere in nature, in physics, in biology, and in social systems. When water goes from liquid to steam, when a population booms, when an epidemic emerges, when riots break out, when a new technology is adopted, when a political transformation takes place — all of them make this pattern. There are three important distinctions on this graph: the point of criticality, the point of saturation, and what lies in between them – the phase transition. Exactly where these points are located on the graph varies between different phenomena, but more important here is understanding the point of criticality, what comes before it, and what lies beyond it. There is this perception on the dissident right that ideas are what’s underpinning change, and this could not be further away from the truth.

There are always tons and tons of different ideas floating around in a society at any given time, but the thing that would make a certain idea stick in history is its compatibility with the prerequisite conditions of a point of criticality on an important S-curve (e.g., the French revolution). If an idea was adopted by the S-curve (the revolution), it would then be carried through the phase transition into the point of saturation, where it would immediately begin to evolve and mutate, but it was nevertheless dependent on sufficient compatibility with the conditions of the point of criticality, which, importantly, can be quite random. Most ideas are forgotten about; the external environment, which is random and complex, is what selects for ideas in an evolutionary process, not the other way around, and the emergent roles attached to those external conditions are then justified by the ideas, even if they are completely paradoxical to what was going on in the phase transition. This means that ideas are mostly useful after the phase transition, not before it.

The consideration of these factors might lead one to question the usefulness of action on an individual or group level, but that’s not right. Action plays an important role in the emergence of an S-curve, especially, or perhaps only, prior to the point of criticality, but it’s of vital importance that one navigates carefully and sensibly. Trying to push a message that’s consistently rejected by the market will only defuse the emergent process, reducing criticality; remember, the environment selects for ideas, not vice versa. Language is also a major problem, not necessarily because the right uses foul or incorrect language, but rather because language is one of the layers on which the white blood cells of the consensus algorithm operates. Another problem with language is that, to a large degree, it has lost its meaning as an effective method of communication — this is a general problem in society, not just for the right. Most people forget what they read and hear about, and how could they not? As soon as one steps outside, one is bombarded with messages and imagery from all directions; there’s too much random noise out there for one to be able to think clearly. In this kind of environment, I think photographic journalism, pictures, and art all have much more potential to accelerate systems criticality, compared to the usage of written or spoken language, because these alternative forms of communication have the potential to bypass much of the learned immunity that most people have gotten used to thinking in terms of.

To summarize, let’s weave some of the above-discussed threads together. Depending on through which lens one views the current state of our Civilization, one draws different conclusions. The problem with Elite Theory as such a lens is not just that it’s misleading and lacks explanatory power; it’s also completely black-pilling when one begins to intellectually extrapolate from it. Just observing how much money and power the elites have may lead one to think that the game is over, but this line of thinking is based on a misunderstanding of how different systems work.

The system is adaptive, not static; roles in systems are emergent, not set in stone. Just as billions can be wiped off a stock exchange in hours, elite roles in systems may lose their power overnight as the underlying conditions of the system change.

The system is open, not closed; the buildup of instability caused by energy/entropy mismatch is likely to lead to new forms of order, not collapse.

The transition between this paradigm and another must not take a century or more to complete; it is true that the accumulation of disorder from an ordered state in a system may take long, but when sufficient disorder is reached, an emergent transition to a new state of systemic order may be very quick, as is shown in the phase transition on an S-curve.

Being cognizant of the dangers attached to competition over shared resources may reduce both infighting and ideological purity spiralling on the right, the latter of which is especially problematic since the market rejects most ideologies anyway, not just right-wing ones.

Cleverly knowing how to apply pressure where it hurts may assist in the emergence of systems criticality, which is a prerequisite for change — this should be the role of vanguard right-wing intellectuals. Here, the framework of Complexity Theory is required to be able to think clearly; because in the modern world, there are no other alternatives.

Like the great Jonathan Bowden once said: “Thinking is the important thing.”

READ MORE about the systemic crises at hand:

When logic is finished with its good work, best to yearn and long for intuition and the assurance that can only come from a connection with the Divine!

Well said. The need to even take into account complexity has been missing in many discussions. Banger of an article.👏