Hans Vogel reveals the five seminal books that deeply influenced his outlook.

There once was a time when educated, literate inhabitants of the European world shared what was essentially a similar literary culture. That situation reached its apogee over a century ago, but of course, there were national and linguistic differences. In those days before TV, radio and the internet and when the movie industry was still in its infancy, people read a lot. The only access to information, knowledge and, often, entertainment, was through the printed word. Hardly a home without books and the higher on the social ladder, the more impressive a person’s library.

In the second half of the 19th century, literacy advanced impressively. By the 1890s, Germany led the world with practically zero illiteracy. On the other end stood Portugal and Romania, with 80% illiterates. In the US, illiteracy among whites stood at 8%, among blacks at 60%. Italy had about 40% illiterates, Belgium 30% and France, England and the Netherlands about 5%. Not surprisingly, Germany was the world’s number one publisher of books, with 25,000 titles in 1900, some 30% of the world’s total. People read because their profession or job called for it, but also as a form of private entertainment.

Although the classics differed from language to language (Shakespeare and Byron; Goethe and Schiller; Racine and Corneille; Cervantes; Dante; Camoens; etc.), in a very fundamental sense all Europeans shared the same literary culture. This culture also comprised the inhabitants of the Americas and the European settlers and residents in the colonial world, and even the tiny numbers of native elites in those colonies, as well as some Chinese, Japanese and Koreans.

Today, the situation is radically different. One out of three eleven- and twelve-year olds in Germany cannot read German, and one in five cannot write properly. In all likelihood, these illiterates are not real, native Europeans, but kids from the Third World or born of Third World parents. Data from a few years ago indicate that the vocabulary of teenagers in England is about 300 words. No doubt the situation is comparable all over Western Europe.

Less and less people read books and if and when they do, these tend to be cookbooks, self-help and how-to books, chicklit, detective books, and cheap novels. However, these preferences are probably the same as they were about a hundred years ago.

Not surprisingly, since I am a historian, I mainly read books that belong essentially to two categories: modern variants of A) Homer’s Odyssey and B) the Holy Bible. As a matter of fact, much of what people like to read falls in these two categories. The Bible is the original “non-fiction” book, brimming with facts (which are, however, impossible to verify), problems and their solutions and all kinds of examples, warnings and useful and practical advice. Of course, it also the original history book. As for the Odyssey, it is the mother of all biographies, autobiographies and novels, describing the trials and tribulations of the protagonist Ulysses, his adventures and encounters, and the ultimate attainment of his goal.

One of the first real books I read as a boy was in category “A”, namely De leeuw van Vlaanderen (1838) by Hendrik Conscience, a novel about the struggle for freedom in early 14th-century Flanders. It is one of the greatest novels of 19th-century European literature, somewhat comparable in atmosphere to Ivanhoe, and a cornerstone of the Flemish nationalist movement. Another early favorite was the Dutch-Flemish comic strip Bulletje en Boonestaak (“Bully and the Beanstalk,” published from 1924 to 1937 in the socialist newspaper Voorwaarts), later available as a series of books.

As for the question as to what my five favorite books at this moment are, that is not an easy one to answer. I might mention two of my favorite works of reference. One is probably the most magnificent ever published: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon in twenty volumes plus supplements (1902--1912), comprising 20,000 illustrations, and 1,800 superb plates and maps. The other one is the 10-pound heavy Dutch biographical dictionary Persoonlijkheden in het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in Woord en Beeld (1938), with 6,000 entries. According to the well-known historian Professor Ivo Schöffer (1922--2012), this work is essential reading for anyone wishing to truly understand 20th-century Dutch history.

As for the actual shortlist of five works, four are in category A. Beginning with the oldest, these are:

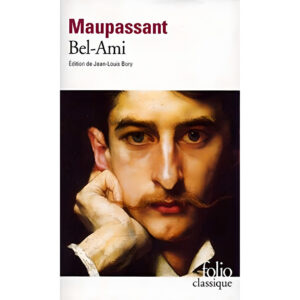

1. Bel-Ami (1885) by Guy de Maupassant

Guy de Maupassant is one of my favorite authors and regarded by many as the inventor of the short story. This is a novel in which an ex-sergeant of the French colonial army in North Africa becomes a highly successful journalist in Paris, basically thanks to his personal charm and charisma, and his ruthless talent for manipulating society ladies. The work not only portrays the corruption of journalism but at the same time its intimate relationship with high politics, which is just as corrupt. In this respect the work retains its intrinsic value, because nothing really has changed. However, as recently as 2012 an English-language movie based on the book flopped tremendously. Much better is the 1939 German movie directed by Willi Forst, which still is worth watching.

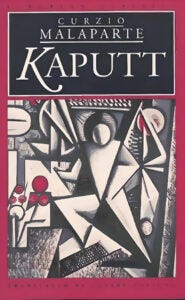

2. Kaputt (1944) by Curzio Malaparte

This magnificent, majestic autobiographical novel, translated into English, French, German, Spanish, Russian, Norwegian and other languages, is without doubt the most important and insightful novel on the Second World War, published in any language. The protagonist, working as a correspondent for the newspaper Corriere della Sera, and also as a diplomat, travels through Europe during the war. He visits Romania and is a witness to the pogrom at Iasi, is sent to Poland where he is the guest of Hans Frank, the Nazi governor, and witnesses the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto. Malaparte vividly describes life at the front lines in the Ukraine, as well as what it was like to work as a diplomat in neutral Sweden. The book is kaleidoscopic, panoramic and also disturbing in that it blurs the lines between what we have been taught is absolute evil and absolute good.

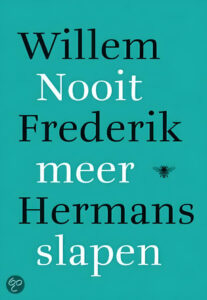

3. Nooit meer slapen (1966) by Willem Frederik Hermans

The book was translated into Swedish (1968), German (1982), English (2006), French (2009) and Italian (2014). Probably the most important Dutch novel of the postwar period, it has strong autobiographical elements (Hermans was a professor of geology at Groningen University) and tells how a young PhD candidate in geology does field work in Norway, looking for meteor craters to confirm a theory that he has developed. The theory is far-fetched, but the protagonist is undaunted. Trekking through the Norwegian wilderness, plagued by dense clouds of voracious mosquitoes impossible to escape, unable to really sleep due to the summer time sun that never stops shining, the search becomes a hallucinating quest, with the main character continuously balancing on the brink of the subconscious. This novel is a very Odyssean metaphor for endurance in the face of insurmountable obstacles. In the end, of course, the initial theory cannot be proved, but the proof that there are no meteor craters is also a tangible, though disappointing result. This is but a minor consolation for the hardship experienced in the wilderness.

4. Almirante Cero: Biografía no autorizada de Emilio Eduardo Massera (1992), by Claudio Uriarte

This is an exhaustive, well-researched biography of Argentinian admiral Emilio Massera, member of the military junta that took power in Argentina in 1976. The junta, headed by army general Jorge Rafael Videla, was led in fact by Massera, who could not officially be the leader because within the armed forces, the navy did not carry as much weight as the army. Maintaining close ties with the Italian masonic lodge P2, noted for engaging in all kinds of sordid and shady business, Massera was the leader in the fight against the urban guerrilla in Buenos Aires and other cities. Actually, Massera personally liked to take part in the secret night-time expeditions as a member of a GT (Grupo de tarea, task force), kicking in doors, lifting people from their beds and engaging in fire fights. As a devout ladies’ man, Massera had many extramarital affairs, including with the famous Italian pop singer Raffaela Carrà. After Argentina’s return to democracy in 1983, Massera’s hopes of becoming a civilian politician were dashed because he was charged with and convicted of murder.

5. La disputa del Nuovo Mondo: Storia di una polemica, 1750--1900 (1955), by Antonello Gerbi

Translated into English in 1973 (The Dispute of the New World: The History of a Polemic, 1750-1900), as well as into Spanish and Portuguese, this book is fundamental reading for anyone wishing to understand the relationship between Europe and the Americas. This is intellectual and cultural history at its very best, analyzing in detail the effects that the discovery of the New World has had on European thought and what it meant for the way that Europeans had to adjust their perception of the world and themselves as a result. Europeans either despised or worshipped the Americas and everything it encompassed. There was, and often still is, no middle way. Eventually, following Hegel, most Europeans came to appreciate and admire the United States, while reserving their contempt for Latin America.

If these remarks induce anyone to actually pick up and read any of the five books discussed, I would be extremely content.

What an excellent list! I have never read any of these. My promise to Mr. Vogel: I shall buy and read all of these.

Honestly, I would love to read a "tour of literature" by Hans Vogel because I suspect that he has a list more akin to twenty or thirty important books!