Graham Greene: The Not So Quiet Englishman

by Richard Wilson

Richard Wilson argues that Graham Greene ignored concerns about posterity and safety, disregarded conventional approaches, and was indifferent to everyone's opinions except those of his close friends. Unconcerned with criticism from world leaders like the Pope, presidents, and dictators, Greene lived his life on his own terms, an approach that proved effective for him.

Some years ago in Chile, after I had been entertained at lunch by President Allende, a right-wing paper in Santiago announced to its readers that the President had been deceived by an impostor. I found myself shaken by a metaphysical doubt. Had I been the impostor all the time? Was I the Other?

— Excerpt from Ways of Escape by Graham Greene

This is the patent age of new inventions

For killing bodies, and for saving souls,

All propagated with the best intentions.

— Lord Byron

I’ve been to India, Pyle, and I know the harm liberals do. We haven’t a liberal party anymore — liberalism’s infected all the other parties. We are all either liberal conservatives or liberal socialists; we all have a good conscience. I’d rather be an exploiter who fights for what he exploits, and dies with it. Look at the history of Burma. We go and invade the country; the local tribes support us; we are victorious; but like you Americans we weren’t colonialists in those days. Oh no, we made peace with the king and we handed him back his province and left our allies to be crucified and sawn in two. They were innocent. They thought we’d stay. But we were liberals and we didn’t want a bad conscience.

— Graham Greene, The Quiet American

Catholics and Communists have committed great crimes, but at least they have not stood aside, like an established society, and been indifferent. I would rather have blood on my hands than water like Pilate.

— Graham Greene, The Comedians

‘You think you are so bad,’ she said, ‘but it was only because you couldn’t bear the pain. But “they” can bear pain — other people’s pain — endlessly. They are the people who don’t care.

— Graham Greene, The Ministry of Fear

Graham Greene was a successful man. I don’t mean the obvious. He was immensely popular, and at the same time a very good writer, great even. One way to measure success is: are my enemies great? Graham Greene’s enemies were. Do they want me dead and can they arrange it? Greene’s most despicable enemies, like Papa Doc Duvalier, threatened to assassinate him. He worked as a spy, Kim Philby was his boss — and lifelong friend. When the entire Anglophone world detested Philby, Greene kept visiting him and wrote the foreword to Philby’s autobiography. His books kept coming, the entertainments and the more serious novels, Heart of the Matter, The Power and the Glory, The End of the Affair, The Ministry of Fear (Fritz Lang directed the film version), The Quiet American. And many more. It’s The Quiet American that I first read, the one that bit me.

Its author was the most popular English writer last century … not just in English-speaking countries but everywhere. Most of his colleagues were men of the Right, Kingsley Amis, Waugh. Many of his English-speaking predecessors were Old Right, or Far Right, Yeats, Pound, T. S. Eliot — Greene, however, was a weird one. He was Catholic and, although he had friends who were right-wing, Greene hobnobbed with old-school leftists, he supported them, sought them out. Granted, the old left has nothing in common with today’s new rainbow-colored, fecal-smelling, fistfuls of misplaced fat and butchered genitalia carrion-smelling hyenoids that we call “the new left.” Save the environment, genderfluid, safe places … more of a liberal thing than a leftist idea, Che would have offed them, Mao, Lenin, Stalin, Pol Pot would have had a field day. Whatever the case, his odd politics aside, his near heretical religious beliefs put away, it’s his skill as a writer that I’m going to write about. His skill and his prescience. His style was straightforward, he didn’t experiment, what he lacked in plot he made up in psychology, in a style that can be called “surgically clean,” albeit a surgical cleanness in a third-world slum. A bullet put in the chamber smelling of a latrine and gunpowder, precision and chaos, mechanical perfection and human stench.

When I read him, I’m constantly underlining or highlighting passages, to return to again and again. These, for example:

Innocence always calls mutely for protection when we would be so much wiser to guard ourselves against it: innocence is like a dumb leper who has lost his bell, wandering the world, meaning no harm.

— Graham Greene, The Quiet American

The world was in her heart already, like the small spot of decay in a fruit.

You cannot control what you love — you watch it driving recklessly towards the broken bridge, the torn-up track, the horror of seventy years ahead.

But I’m a bad priest, you see. I know — from experience — how much beauty Satan carried down with him when he fell. Nobody ever said the fallen angels were the ugly ones. Oh, no, they were just as quick and light and…

— Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory

It infuriated him to think that there were still people in the state who believed in a loving and merciful God. There are mystics who are said to have experienced God directly. He was a mystic, too, and what he had experienced was vacancy — a complete certainty in the existence of a dying, cooling world, of human beings who had evolved from animals for no purpose at all.

You know what the fellow said — in Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace — and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.

It was as though our love were a small creature caught in a trap and bleeding to death: I had to shut my eyes and wring its neck.

His “heroes,” if you can call them that, are not so black and white. Greene famously said, “The world is not black and white but black and gray.” (He also hated people who use quotes). His heroes are infamous: The proto-Ligotti anti-natalist priest in The Power and the Glory who is being hunted in Revolutionary Mexico; Scobie, the depressed, cheating policeman in wartime (WW2) Africa; the famous architect Querry, protagonist of A Burnt-Out Case who spurns fame and the world (but the world finds him) by escaping to a leprosarium in Africa; Maurice Castle, mild-mannered husband and spy in The Human Factor; Arthur Rowe, being chased by Nazi assassins in wartime London in The Ministry of Fear. In addition to the novels, he wrote short stories and hundreds of film reviews and many screenplays and a few plays. Two travel books, one set in Mexico, one in Liberia.

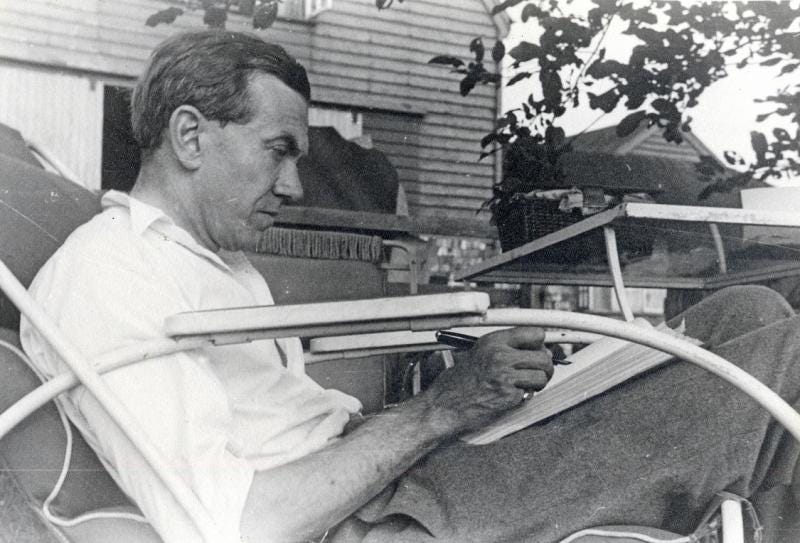

Greene spent a lifetime in foul places. Liberia, Kenya, Malaysia, Vietnam, Belfast, Mexico during the anticlerical purges, Central and South America. According to Greene, his favorite places were Vietnam and Africa. His trip to Vietnam inspired one of his greatest books, The Quiet American. He knew that France would leave, would surrender Vietnam, that the Americans would come in. He always knew how it was going to end, he at least knew what was going to happen. He was no prophet. Prophets aren’t really soothsayers, they have their finger on the pulse of people, of states, of civilizations, of an era. Graham Greene had the pulse of colonialism and of the upstart colonial power, America. The Vietnam War was the beginning of the end of American hegemony. Greene knew France’s colonial project was unraveling. He knew the Americans would inject themselves and make the same mistakes, which ones, he didn’t say.

Just reading the title — The Quiet American — makes me laugh. Why? Because the stereotype is always the loud American. When Graham Greene wrote The Quiet American, 1955, the world hadn’t experienced a tourism boom and had not experienced the whale pods of khaki- shorted, backpacked, sandal-wearing loud American tourists… yet. We are a loud tribe. When I first came to Russia, I watched the muteness of Russians and lowered my volume. (This volume of mine goes up in times of stress or booze). America was on the cusp, on a cusp, at a turning point then and Greene was prescient enough, prophetic enough, to feel it. America then felt that they alone could change events. That because the century starting after the Second WW was to be their century, a century of American greatness. A century not of isolationism, a century where the Republic stays inside its own borders minding its own business. In reality the opposite occurred. In the period from 1949-1960, America was not quiet in foreign interventions: 1949, coup in Syria, 1952, coup in Egypt, 1953, coup in Iran, 1958, Guatemala, same year they fomented a rebellion in Indonesia. These are the ones we know of … and the one plot they were most involved in was Cochinchina, French Indochina, Vietnam. They came quietly, arrogantly, they left, literally running for the helicopters and firing at the Viet Minh. I saw it as a little boy on TV, my grandpa, drunk yelling, “Everyone, come here, look at this.” I saw the helicopter lift off on TV, with my grandpa, the last of the Americans, barely escaping Charlie.

The novel’s plot, of American exceptionalism guiding the CIA to meddle in foreign nations, innocently believing they are helping the poor people, naively bringing death and destruction with their vision of American exceptionalism, at home and abroad. Their belief in what military analyst and author of one of the greatest books on Vietnam ever written, Street Without Joy, Bernard Fall called “the religion of technology” and their panoptic belief that, since they have better technology, they can and will defeat the primitive Viet Minh. This idea, this religion was brought into every single US foreign intervention and it never worked. They still, with the Russia-Ukraine war, shriek about how their technology is going to win the war (just supply the meat, Zelensky). Afghanistan, sandal-wearing hillsmen brought America to its knees, before that, the ur-conflict, the one that created the mold, was Vietnam. Even before the US, it was the French with the same religion of technology that thought it would be the decisive factor.

The West is still battling an ideology with technology and the successful end of that Revolutionary War is neither near nor is its outcome certain.

— Bernard B. Fall, Street Without Joy

Greene was in French Cochinchina, French Indochina from 1952 to 1955, every winter, working as a foreign correspondent, watching the disintegration of the French colonial system in Southeast Asia…it was also collapsing in Algeria…indeed, the colonial system was falling apart everywhere, Malaysia (then called Malaya), Kenya, Libya, Hungary against the Soviet Union, Sudan, Morocco, Tunisia, Cambodia, Laos, Belgian Congo, Puerto Rican nationalists tried to assassinate Truman, Egyptian Nasser overthrew the monarchy and nationalized everything. In other areas colonialism was digging in, China got Tibet and Hong Kong, Greenland became a part of Denmark, Alaska and Hawaii became states.

The American critics attacked The Quiet American for its depiction of imperialistic Americans in the third world, with their “deadly innocence.” Their holy mission was to save the world and recreate it in their image, the book’s characters, Fowler, the English journalist who has been in Saigon for many years, smokes his bowls of opium at night, has a straight-backed, longhaired Vietnamese lover, Phuong, who is much younger than him. Her sister wants Phuong to have better husband material and is on the lookout for a promising match, not an old washed-up journalist who is still married to his very religious wife back in foggy, dreary England. From stage left: here we now see Pyle, the zealous American, new to ‘Nam, who preaches with gusto the need for a third force in Vietnam, for democracy, of course. One that isn’t the wan, dysfunctional puppet government of Diem. Nor is it the efficient, deadly movement of Commie Ho Chi Minh. Pyle, and his American superiors, thought perhaps the Caodists, the strange religious sect in the Southern Delta, whose saints include Victor Hugo, Buddha, Christ, Sun Yat Sen and others, like Trang Tring, the Vietnamese Nostradamus, could be this “third force,” but there was another, a renegade officer, General Trình Minh Thê, or General Thê, as he was known. (Later, in 1955, he would be assassinated by a sniper who shot him in the back of his head. He had many enemies, some say the French did it) Pyle falls for Phuong, Phuong’s sister is excited about this much more desirable prospect, young, American, single. Phuong gives it some deep thought and eventually moves in with Pyle.

Next, after Fowler returns to Saigon, there is a public bombing at a cafe, the Yanks declare the Communists as the culpable party, everyone, police included, know it’s the American-backed General Thê. Pyle meets Fowler telling him of his upcoming marriage to Phuong. Fowler is incensed — at the Americans’ culpability in the bombing, not so much his stealing his lover — and helps to get Pyle killed. He and Phuong get back together as if nothing happened. His wife writes that she will grant him a divorce. End.

Since the end of Vietnam, American exceptionalism and “innocence” have been on a non-stop world tour. Their last successful “third force” play was,of course, in Ukraine. The two dominant parties in Ukraine, that hobbled together nation of disparate parts at each other’s throats, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, had a controlled politics, one party supported by north and west, and the other, Party of Regions with support in the south and west and in Crimea. The US supported a third force to break this tepid, boring deadlock in Kiev. CIA support for the far right in Ukraine began shortly after the collapse of the USSR. Some say it never stopped since the end of WW2. At Maidan, it was the Svoboda Party members of Tyanbuk, Pravy Sektor, all the successors of Bandera, on the fringe of Ukraine in their West Ukraine homes, raging against first the Soviets, then the Russian hordes. The CIA supported them with training, with money, at Maidan, they took control and a country that no one ever thought would be wrested from the Russian sphere of influence was taken, by force. Dozens were killed. They blamed Russia and Yanukovich; at Odessa the same year, fifty odd people were burned alive by this third force. America. Greatest Country on God’s Green Earth, my uncles would proudly say, cracking open that swill called Budweiser, of course most of them hadn’t been anywhere…except Vietnam. So, there is that. The connection between the Vietnam debacle and the current Ukrainian debacle is an American hubris that has not abated, but only, like a strange movie monster, has become larger, deadlier, now running through the world, smiling, covered in a deadly disease, their cowbell, round their white American neck, sweat, filled with good intentions and a good night’s sleep, roll down the hot skin of the not so quiet Americans in these foreign badlands.

Like Americans during Vietnam, most Americans are against the involvement of the USA in Ukraine. After the failure of Afghanistan, that graveyard of Empires, after the failure of Iraq, the failure of Syria, of Central America, of coups, assassinations, in Africa, South and Central America, of American rapine in the new Russian Federation, Americans and their satrapies still believe in the urgency and power of a nation that has suicide as the number one cause of death, a nation that is now officially more obese than overweight. A nation obsessesd with transgenderism and self hate. Perhaps it’s their comeuppance, it’s a strange sort of arrogance to think one can change the world and steal its resources, all with the power of arms, of good teeth, charm and gangsta rap, porn and deep-fried Oreos.

Exporting democracy, unbelievably, still sells tickets to the auditorium. In small town America, Germany, Ukraine, Asia, Africa — which is baffling, considering the two faces/one party democracy in America which is collapsing under its own unbearable weight of cellulite, kitsch and the idea of American exceptionalism. It does seem as if the chickens (poisoned and bloated with GMOs, steroids) have come home to roost.

Graham Greene, famously, had issues with American foreign policy. Most of us do, he also had problems with French foreign policy and British. All colonialism was his enemy, also the Papa Docs of the world, many anti-colonialists were in his sights as well as the colonialists. As much as Greene detested America, his bedside reading material was always the letters of Ezra Pound.

His life seemed to be written by him:

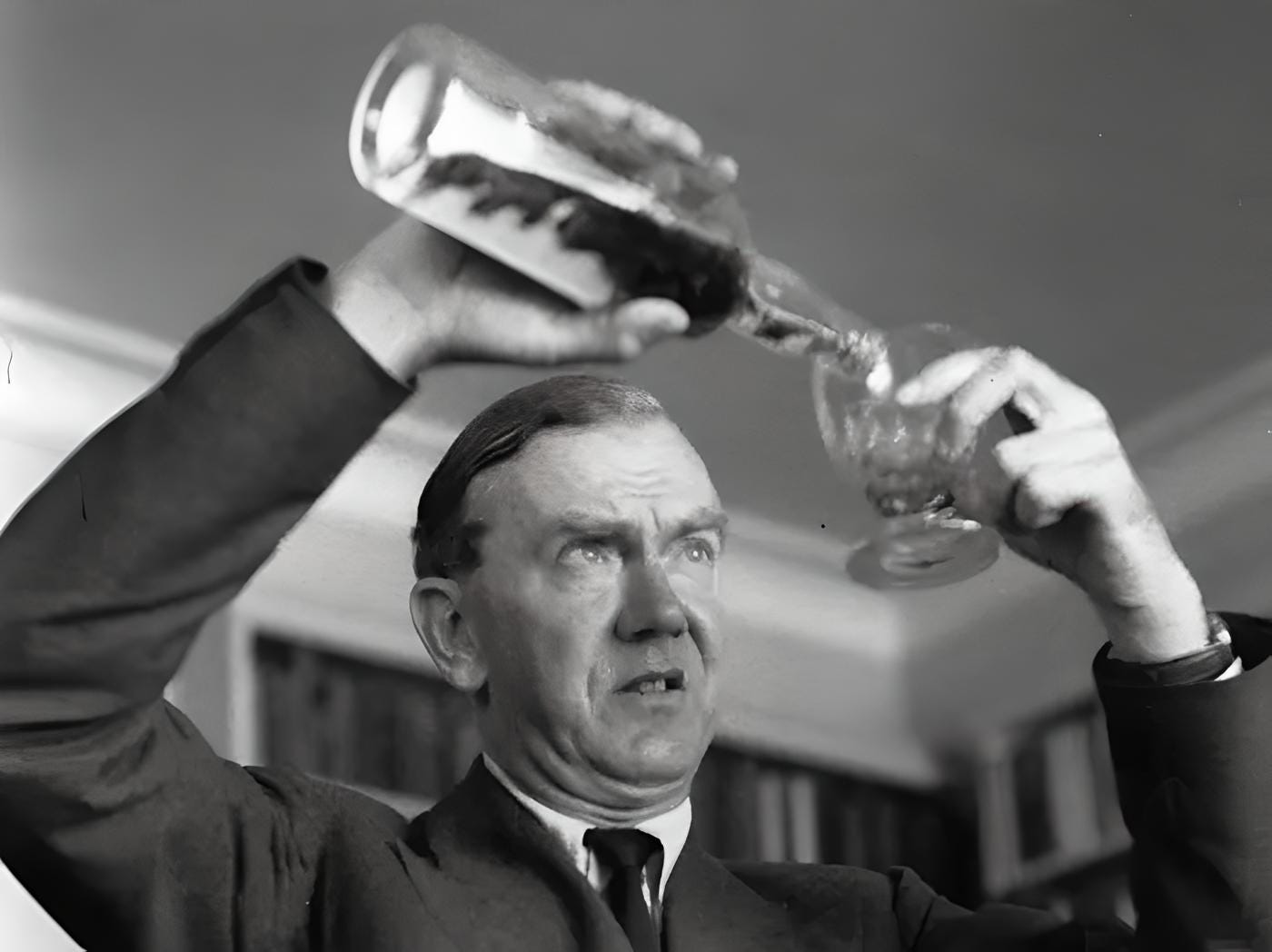

He was Catholic and a “fellow traveler,” friends with dictators, liberation theologians, Sandinistas, Ho Chi Minh, he was alcoholic, bipolar, a sexually promiscuous serial cheater, he gave money away to those less fortunate, to Communist rebels, to monasteries, he saw Modern Liberalism as the greatest evil and an answer to Liberalism he saw in the teleological Communist movement and in Catholicism. The Church today, like then, doesn’t quite know what to make of Graham Greene, this self-styled Catholic atheist, was he good for the Church? Or was he a double agent of … Moscow, or worse, Satan? Some men define the century, some men more than others, Greene was last century. He knew its movers, its victims, its influencers, monsters and saviors. All of what he lived became grist for the creative mill of his mind, what chaos he lived and spoke in favor of, alas, he wrote the cleanest prose of any writer last century.

It comes upon one, the feeling and knowledge that literature is dead at 50. Everything worthy of one’s time has been read and reread, one’s reading past is like romance, it consists of women you’ve experienced (books read), women you wanted but for some reason could never have (books you wanted to read, but you couldn’t because of time, circumstance, mien), women you could never have been with, ever (books you’d not have read in no way, shape or form). Graham Greene was in the third category. His name said to me, everything was droll, dull, dreary. Why? A holdover from my twenties and thirties when names meant everything, either for characters, roles, nom de guerre or plume. Graham Greene was boring form the get go. At 50, increasingly, other writers I worshipped, lauded Greene, some said he was the greatest English writer after WW 2. I had had enough and was at a used English bookstore in Moscow and read The Quiet American; the book rototilled my mind, my opinions and thick thinking. After The Quiet American I read all of his serious novels, Greene divided his books into serious and entertainments, even the entertainments were serious and the serious ones entertaining. The more I read of his work, the faster horse he became, overtaking all of my hallowed authors, the race is over now and Chekhov is still the winner, Tolstoy next and Greene third. Part of my Holy Trinity of authors.

Where Chekhov was a moderate who wrote about extremes and especially death and loss, Greene was an extremist who wrote of the middle people caught in decision-making, caught in traps of their own making.

He was the English-language author of the century. Not just myself but many people think the same. Orwell’s moral position has fallen, Greene’s has risen. Greene was no monk, far from it. In fact, he was a bouillabaisse of opposites. A Catholic, but hated being called a Catholic writer, a man of the Left — he had a fondness for Communist movements, and a hatred for America and Americanism. But, he also fought against Communism’s attacks on individuals. Before Benoist’s maxim of a preference for Soviet helmets in Paris instead of McDonald’s in Brooklyn, Greene beat him by stating he’d rather live in the atheist Soviet Union than the “modern materialistic liberalism of America.” The Soviets, he said, “only killed the body, the Americans killed the soul.” He laughed at prophets but was a prophet himself, even if accidentally. In an interview in the early 80s with Martin Amis, he said, “Only the KGB, or a man from the KGB, can reform and save Russia.” Everyone thought he was nuts, perhaps Our Man in Moscow is laughing. A Christian writer who lived like a hedonist, affairs and alcohol, opium, hatreds, jealousies, backbiting, he never backstabbed. Long after his old boss (Philby) revealed himself and had started a life in Moscow, Greene, perhaps the most famous English-speaking writer on earth, wrote Kim Philby’s foreword in a memoir (detractors call Philby’s memoir his apologia). He would meet Philby in Moscow six times after Philby’s defection. He never left Philby, when the entire UK had Philby as scum, a traitor, it was Greene who said, “He never betrayed his beliefs, therefore he was never a traitor to what matters most.”

He traveled to the worst places on earth last century, some are still the worst, and these travels made it into his work: Haiti, The Comedians. Vietnam, The Quiet American. Mexico, The Power and the Glory. Africa, The Heart of the Matter and A Burnt-Out Case. His travel book about a trek through the Liberian jungle, Journey Without Maps, I read on the Moscow-Simferopol train, a 24-hour trip, two days after Ukraine had bombed the Kerch bridge, I was deep towards the end of the book when the announcement came on, “We are approaching the Kerch Bridge,” suddenly I felt as if I were thrust into “Greeneland.” Outside were low-flying helicopters, down below were boats with lights, at the first station after the bridge, hundreds of troops.

What is “Greeneland”? Arthur Calder-Marshall coined the term Greeneland to describe the unique world of Graham Greene.

For a while it became a British parallel for the Americanised “noir” genre.

Key features were a setting showing economic depression, immoral and amoral activities, zero remorse for heinous acts, a moral vacuum, overall seediness, tainted people and places, rampant corruption and failure in desire and action. But it is not without relief or moments of redemption. Sometimes. Many times there was no redemption.

Greeneland is usually Third World: dangerous, disease-ridden, there is the foundation of seediness, Greene even thinks he popularized the word “seedy.” To create the novels, he traveled to Central America, Africa, French Indochina, the Caribbean. Kenya during the Mau Mau Rebellion, at the end of French Rule in Vietnam, in civil wars, rebellions, outbreaks, volcanoes of violence and disease together. Graham Greene was last century, was the human condition, wrote the human drama with finesse, power and an unparalleled talent. Even though he was a “burnt-out case,” with manic depression, a womanizer, an alcoholic, his life was messy … yet, the mess of his life never went into his writing.

Richard Greene (no relation) wrote the definitive biography, The Unquiet Englishman, and in the Introduction says this of Graham Greene’s writing:

Like any writer, he could occasionally be uneven; still he maintained an extraordinarily high technical standard in his writing, and many of his insights into human character and motivation, politics, war, human rights, sexual relationships, and religious belief and doubt remain compelling and provocative. It is hard to think of a recent writer in English who comes as close to greatness as he does.

John le Carré believed that in his time Graham Greene “carried the torch of English literature, almost alone.”

Sometimes, it feels like the world we are in has a light cast from Graham Greene, he is walking ahead of us, and everything we encounter now is being written by a not so quiet Englishman.

Great piece. I too started with the Quiet American and found it prescient.

I'm working my way through all his books. I think towards the end he dropped the serious/entertainments distinction.

One humorous anecdote I'm aware of is the satirical magazine Private Eye in London ran a Graham Greene competition in the 60s, inviting people to write a short story in the style of Greene. Greene himself entered and won second place!

Excellent article! I need to read all his other stuff. I may not have had the maturity to appreciate them in years past, though.

I can't be called a Greene fan, really, as I've not explored most of his works, but his novel, "The End of the Affair," affected me greatly. Read it long ago when still a lapsed Catholic on a wayward path, dabbling in all this and that nonsense and bundles of half-truths. Yet, the understandable depth of Maurice Bendrix's puzzlement at the ironclad fidelity of Sarah Miles to her faith-prompted promise just struck at my heart like few other novels have. That was one of the most powerful novels about Catholicism that may have helped draw me back to the Faith several years later, even if Greene kept the core conflict at the utterly human level that could resonate with anyone through Bendrix. The movie version foreshortened some elements (due to the nature of cinema vs. books), but was overall a good adaptation.