God of War: The Legend of Ungern-Sternberg

by Joakim Andersen

Joakim Andersen reviews a book on Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, the Baltic German and Russian Imperial officer-aristocrat who chose the way of the warrior and became a living legend.

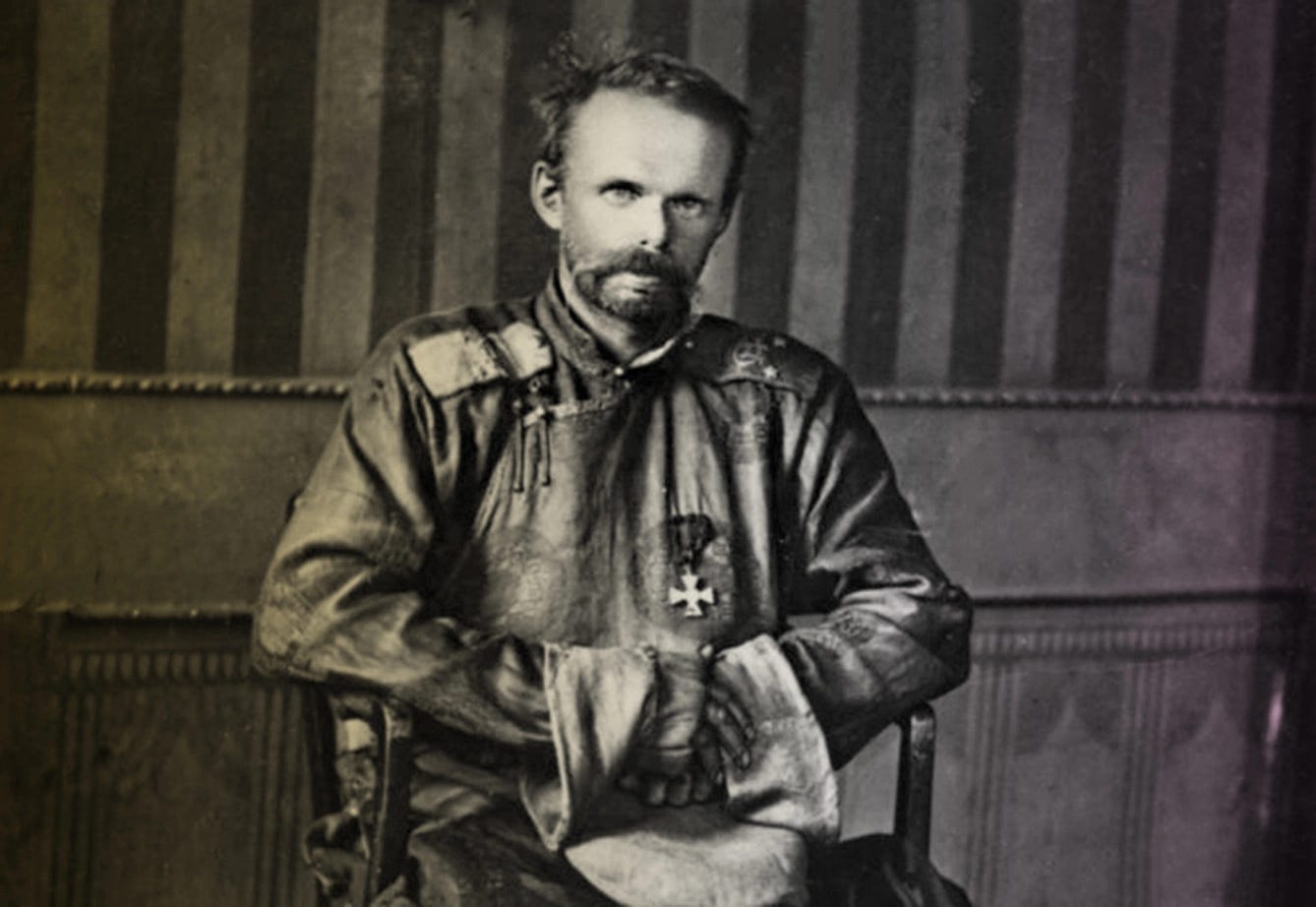

Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg was a fascinating and inspiring person. He belonged to the Baltic German aristocracy and fought on the White side during the Russian Civil War. Afterwards, he made his way to Mongolia and practically became the ruler of the country, which he planned to use as a springboard to unite a traditionalist East against the infection of the West. It is said both that he converted to Buddhism and that, in parts of Asia, he was regarded as an incarnation of the god of war himself.

In Red propaganda, he was described as “the Bloody Baron,” despite the fact that he came nowhere near the genocide that communism brought, including to Mongolia. During the 1930s and 1940s, about 100,000 people were executed in Mongolia—among them around 50,000 lama monks. That those who orchestrated the murder of nearly 10% of the country’s population simultaneously refer to Ungern-Sternberg as “bloody” comes across as almost distasteful.

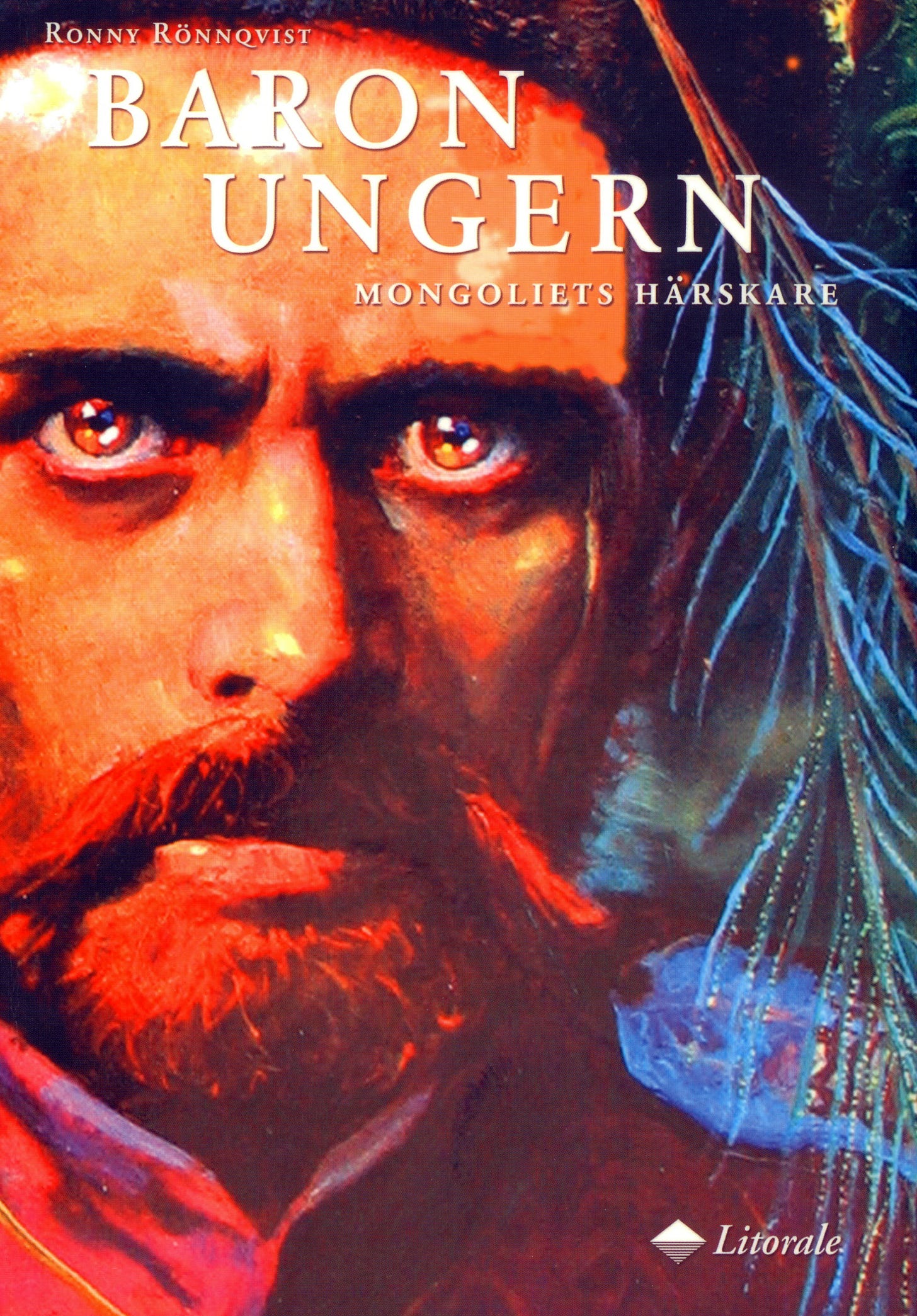

Ronny Rönnqvist worked for many years at Finnair, where, for a couple of decades, he handled aviation policy and international relations, including in the Far East. This contributed to his interest in the Baron, among other things, and he has written a highly readable study about him, titled Baron Ungern: Ruler of Mongolia.

Rönnqvist portrays the Baron’s idyllic upbringing in the Baltic German aristocracy, belonging to an ancient family with roots dating back to the mid-13th century. Violence and arson attacks directed at his family and friends during the revolutionary year of 1905 likely awakened the young Roman’s implacable hatred for revolutionary socialists. He was something of a rebel in his youth and often clashed with both teachers and officers.

The Baron was a man of seemingly contradictory traits, and Hermann Keyserling, a friend of the family, compared him to a tiger. He had a fierce temperament and stated that he could not endure a peaceful life. Baltic knightly blood ran in his veins, and he sought war itself. His bravery during the First World War earned him the Order of St. George. The White General Wrangel described him as a brave officer without fear, with an iron physique, wild energy, and the ability to sleep and eat with his Cossacks in a way few officers did.

At the same time, Keyserling described him as one of the most metaphysically and occultly gifted individuals he had ever met. He was thus drawn early on to Lamaist Buddhism. Like perennialists such as Guénon, he had a theory about the reconciliation of the world’s religions; his forces included everyone from Lamaists and Christians to Muslims and a few Jews. He also believed in reincarnation and surrounded himself with native Lamaists and shamans during his campaigns in Mongolia.

“It’s a kind of religion… in fact, Lenin has founded a new religion.”

– the Baron on communism

His worldview was that of the classical right. The Baron was a monarchist and hated “the three evils”: Jews, Americans, and socialists. He saw the West, “the rotten West,” as emasculated by liberalism and materialism. Hope thus lay in the East. He had geopolitical plans first to liberate Mongolia and then to create a federation including Greater Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Alongside China and Japan, traditional Asia would then turn against the rotten West, and the Tsardom would be restored. It’s worth noting that von Ungern here strongly resembles later Eurasian ideas advanced by several Russian intellectuals and, in our own time, by figures such as Gumilev and Dugin.

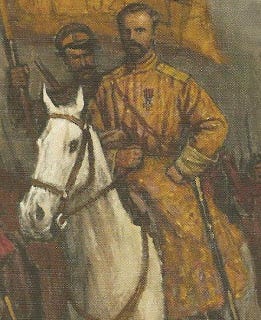

During the Civil War, he joined the White forces in Siberia, where he fought alongside Semenov and units of Buryats, Tatars, Cossacks, and other anti-Bolshevik groups. In 1920, when the situation was dire, he chose to march into Mongolia. The country was effectively controlled by Chinese warlords, and von Ungern could be hailed as a liberator when he expelled them and restored power to Bogd Gegeen, the “Living Buddha.”

The Baron came to be surrounded by many legends. He was believed to be able to read minds and to be protected by supernatural forces. Among the people, he was called tsagaan baatar, the ‘white hero.’ Many saw him as a reincarnation of the god of war and protector deity of Mongolia, Jamsaran —or even of Genghis Khan.

“For a thousand years, the Ungern-Sternbergs have given orders to others. They have never taken orders from anyone.”

– the Baron to the people’s tribunal that sentenced him

During this time, as he also fought against the Reds and Chinese troops, he established ties with several Asian leaders. He had good relations with Japan and had Japanese bodyguards, some of whom fought by his side to the very end. He also had connections with several Chinese warlords. His army was a truly Eurasian force, consisting of Tibetans, Mongols, Japanese, Chinese, Russians, and even a Swede.

Rönnqvist’s study follows the Baron from childhood to his final defeat and trial. The Baron comes across as death-defying and unwavering in his ideals to the very end. After his execution, it is said that the whole of Mongolia prayed to the god of war. The Bolshevik conquest of the country, as mentioned above, led to both a demographic and cultural genocide.

It is a richly illustrated book, in which Rönnqvist addresses such topics as Ossendowski’s descriptions of the Baron, the rumors about his marriage and hidden treasure, and the exaggerated stories about his bloodthirstiness. He also gives a good depiction of the environments in which the Baron operated. In short, it is highly recommended for anyone who wants to get to know this born warrior and Eurasian traditionalist more closely.

(Translated from the original Swedish article)

All my homies ride for Sternberg

Fascinating how Ungern-Sternberg's vision prefigured Dugin's Eurasianism by decades. That detail about him integrating Lamaists, Christians, Muslims, and even Jews into his forces really undermines the simplstic 'bloody baron' narrative. Seems like he genuinely believed in a traditionalist coalition across faiths, which is kinda rare for that era.