Éliphas Lévi and the ‘Profanation’ of Tradition: Part Two

by Dr. Kerry Bolton

Dr. Kerry Bolton explores the intricate connections between secret societies, Masonic traditions, and the historical underpinnings of the European Union, shedding light on their influence in shaping Kalergi’s vision of contemporary Europe.

Read part one here.

Anti-Tradition and Revolution

Levi devotes an entire section of The History of Magic to the subject of ‘Magic and Revolution’.33

Continental Masonry became the current for spreading atheism and materialistic doctrines in the manner described by Guénon.

Some particularly interesting commentary on the role of secret societies comes from Conrad Goeringer, the Director of Public Policy for American Atheists and staff writer for the American Atheist Magazine. Goeringer, a well-known atheist scholar in the United States, often focuses on such subjects, and while eschewing any notion of ‘conspiracies’ nonetheless has written of the mystical association of revolutionary secret societies in a manner that accords with the ‘counter-’ and Anti- Traditional descriptions of Guénon and the ‘profanation’ remarks by Lévi:

While there are many currents to this period, one of the fascinating and little-explored backwater eddys of particular interest to atheists and libertarians is the role of Masonic lodges and ‘secret societies’ during this time. Surprisingly little objective historical work exists on this area. The drama of social revolution and intellectual apostasy was taking place not only in the streets of Paris, or the open fields of Lexington and Concord, but in countless lodges and sect gatherings and reading societies as well. These conclaves, with their metaphorical-hermetic secrets, symbolism and lore, were the crucibles of ‘impiety and anarchy’ so bemoaned by church dogmatists of the time like the Jesuit Abbé Barruel..….34

Note the reference to ‘[t]hese conclaves, with their metaphorical-hermetic secrets, symbolism and lore’ as fomenters of ‘impiety and anarchy’, and the description parallels that of Lévi very closely.

It was in France, the homeland of both Lévi and Guénon, that these profane, Anti-Traditionalist and Counter-Traditionalist currents coalesced into the Grand Orient. One does not have to delve into arcane manuscripts or derided conspiracy books such as those of the aforementioned Abbé Barruel35 or Professor John Robison36 to discover the ideology of the Grand Orient. It is openly described on the order’s website, where the ‘profane’ slogan of ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’ is prominently displayed:

But in this period when the new ideas of Liberty and Equality were to be born, which would lead to the French Revolution and the Republic, France entered the age of Enlightenment. From being a sort of ‘club’ as in England, the Masonic Lodges, which very quickly spread in our country, became a sounding board for these great new ideas and turned into places where debates about the emancipation of Man and Society took place.

The Grand Orient de France which was set up in 1733 and was, until the end of the 19th century, the only Masonic Order in France, is still fighting for these ideals…

For the freemasons of the Grand Orient de France, the search for progress has always been the force behind their reflection and their activities, to such an extent that this principle is an integral part of the tradition of this form of Masonry. We are the heirs of men and women who all, in their own way, worked to improve humankind: Voltaire, La Fayette, Garibaldi, Auguste Blanqui, Victor Schoelcher, Emir Abd-El-Kader, Louise Michel, Bakunin, Jean Zay, Félix Eboué, Pierre Brossolette and so many others…37

The Anti- and Counter-Traditional currents involved in the fomenting of revolution in France were described by Lévi with references to an enigmatic figure suddenly emerging upon the scaffold of the guillotined King:

Jacobinism had received its distinctive name before the old Church of the Jacobins was chosen as the headquarters of conspiracy; it was derived from the name Jacques – an ominous symbol and one which spelt revolution… while those who were prime movers in the French Revolution had sworn in secret the destruction of throne and altar over the tomb of Jacques de Molay. At the very moment when Louis XVI suffered under the axe of revolution, the man with a long beard…. ascended the scaffold and, confronting the appalled spectators, took the royal blood in both hands, casting it over the heads of the people, and crying with his terrible voice, ‘People of France, I baptise you in the name of Jacques and of liberty!’ So ended half of the work and it was henceforth against the Pope that the army of the Temple directed all its efforts.38

This mysterious figure – assuming legendary proportions - was talked about throughout France at the time of the Revolution. Lévi states that the words he quotes from this figure, on the execution of the King in the name of Jacques de Molay and the baptising of the people with the King’s blood, were told to him by an old man who had been present. Lévi, describing the prelude to the execution of the King and the proto-Bolshevik atrocities being conducted against the priests, alludes again to this strange figure:

Amidst the pressure of civil war, the National Assembly suspended the powers of the king and assigned him the Luxembourg as his residence; but another and more secret assembly had ruled otherwise. A prison was to be the residence of the fallen monarch, and that prison was none other than the old palace of the Templars, which had survived… to await the royal victim… There he was duly imprisoned, while the flower of the French clergy was either in exile or at the Abbey. Artillery thundered… unknown personages organised successive slaughters, while a hideous and gigantic being, covered with a long beard, was to be seen wherever there were priests to murder.

As one who was beside himself, he smote unceasingly, now with the sabre and now with axe or club. Arms broke and were replaced in his hands, from head to foot he was clothed in blood, swearing with frightful blasphemies that in blood only would he wash…39

The French revolutionaries, propounding rationalism, nonetheless sought to establish counter-traditions and religious profanations, indicating what Brossolette and so many others said in regard to atheism and materialism being a façade by which to destroy tradition in order to erect a new order based on a counter-tradition. Robespierre advocated the Cult of the Supreme Being. Jacques Herbert and Pierre Gaspard Chaumette advocated a Cult of Reason, both to be worshipped as substitute civic religions.

The counter-tradition they sought to impose had its own idols, liturgy, saints and dogma. Babies were baptised not to the ‘Father, Son and Holy Ghost’, but to ‘liberty, equality, and fraternity’. In 1793, the word Sunday (dimanche) was dropped; the Gregorian calendar was replaced by a French Revolutionary calendar, and it was prohibited to ring church bells, display the Christian cross, or hold religious processions. The Archbishop of Paris was obliged to resign his duties and was forced to wear the red Cap of Liberty instead of the Bishop’s mitre. On 10 November 1779, a Feast of Liberty was held in the cathedral at Notre Dame, and an altar was erected to the Goddess of Reason, represented by an actress who had been paraded triumphantly through Paris, an action strongly suggestive of a stereotypical Black Mass.

The revolutionary regime adopted symbols of occult and mystical origins that would be contrary to a supposedly rationalistic state, indicating that the regime was intended to establish a counterfeit religion. Illustrations of the Revolutionary ‘Declaration on the Rights of Man and the Citizen’ show two tablets in substitute for the Ten Commandments. Above the ‘Declaration’ is the All-Seeing Eye within a radiating triangle. On each side of the tablets are winged angels. Given the anti-Christian character of the Revolution, it does not seem plausible to regard these beings as depicting any biblical angel, but presumably the reverse. Below this is the self-devouring serpent, a specifically occult symbol.40

Another French revolutionary symbol comprises a balance within which is a radiating eye surmounted by the revolutionary Phrygian cap. The self-devouring serpent surrounds the symbols, with the motto ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’ beside it. As interesting as the presence of the All-Seeing Eye in French revolutionary iconography is the presence of the equally mystical and ancient self-devouring World Serpent, often referred to by its ancient Greek name Ouroboros, which translates as ‘tail devourer’. The symbol is also associated with Gnosticism and Alchemy; a cosmic symbol of destruction and renewal. It is a widespread symbol. Nothing of this indicates rationalism or ‘the Enlightenment’, but rather the Counter-Tradition. It is reminiscent of the title page of the Encylopédie of Diderot, one of the philosophical foundations of the French Revolution. Diderot and his colleagues published the Encyclopédie as a means of supposedly discrediting religion through science. Why then does the title page depict a winged ‘angel’, radiating, or illuminated as one might say, while on the ground around him conspicuously lie the squares and callipers symbolic of Freemasonry?41 Why are the foremost rationalist minds of the day, allegedly seeking to undermine ‘superstition’, depicting their compendium of world knowledge with an ‘angel’? What manner of ‘angel’, radiating light, is it supposed to be?

Revolutionary Ferment

The revolutionary ‘atheists’ flocked to the lodges during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, where they ‘worked the degrees’ of the supposedly ancient ‘Mysteries’. Are these the actions of atheists, materialists and rationalists, or of ‘counter-initiates’, only using secular ideologies as a means of destroying traditional societies?

Philippe Buonarroti, the Italian exponent of the French Revolution, was initiated into Masonry in 1786. In 1808 he formed ‘Les Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits’. Like the Illuminati, within the group was an inner circle organised to realise his political aims. Dr. John M. Roberts believes Buonarroti might have joined an Illuminati-influenced lodge in 1786. Buonarroti had a major influence on Auguste Blanqui, and through his book Conspiration pour l’Egalité dite de Babeuf, suivie du procès auquel elle donna lieu he was a major influence on the 1848 revolutionaries. Roberts describes Buonarroti as having established a ‘career as the Grand Old Man of secret societies, advising republican revolutionaries in Italy right down to a young Mazzini…’42

Buonarroti had co-founded, with Francois Babeuf, the Society of the Pantheon, one of the first of the revolutionary secret societies to emerge from the French Revolution, believing the Revolution had failed. Buonarroti organised a group of ‘Philadelphe’ Masonry within the Lodge ‘Amis Sincères’. Roberts states:

What may be termed the first international political secret society, the Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits, was founded by Buonarroti, perhaps in 1808. Only freemasons were admitted to it. The Elect were aware that they were to work for a republican form of government; only the Areopagites knew that the final aim of the society was social egalitarianism, and the means to it the abolition of private property.43

These were the precursors of Marx, the dialectical materialist par excellence, who condemned superstition as an opiate of the people, yet this did not prevent even Marx himself from being initiated into the ‘Mysteries.’ Marx’s Communist League and the Communist Manifesto did not emerge from a void. Marxism was the nineteenth-century culmination of the counter-tradition of a long line of secret societies.44

Louis Blanqui was a follower of Buonarroti, and organised the League of the Just. German émigrés in Paris formed their own branch called the League of Outlaws that became the Communist League, and in 1847 they asked Marx to write the Communist Manifesto. It is from Blanqui that the dictum about the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, now credited to Marx, originated.45

Marx was initiated into the pseudo-Egyptian Mysteries of Memphis-Mizraim Masonry. Prof. Mark Lause, a labour historian,46 writes:

…Certainly, the tangled history of freemasonry has largely mirrored the political and social views of those drawn to the craft, and some of those drawn to the more peculiar pseudo-Egyptian forms of the order reflected views that were accordingly distinctive.47

The Rite had been founded in 1779 by the Cabalistic mystic Cagliostro, one of several charlatans conning high society during the eighteenth century. He was the Rasputin of the French Court who helped bring the monarchy into disrepute. Lévi states that Cagliostro was ‘an agent of the Templars’, (or at least affected this), and was, ‘like the Templars, addicted to the practices of Black Magic’.48

Lause cites Boris Nicolaevsky49 as an authoritative source, in stating ‘that the nineteenth-century Order of Memphis actually did mask the ongoing revolutionary activism of French radicals both at home and abroad, strikingly so in the case of émigré circles at London’.50 This confirms the statement by occult historian Lewis Spence, who in a laudatory entry on Cagliostro writes that Mizraim preached the communistic doctrines of the Illuminati, including feminism and republicanism.

In 1785, Cagliostro was implicated in a scandal within the French royal court and exiled himself to England, where he wrote revolutionary propaganda against the monarchy and declared that the French throne would be overthrown by revolution. His 1786 ‘Letter to the French People’ declared prophetically that the Bastille would be stormed and its governor killed.

Spence states that Mizraim had been set up to subvert the traditional society of Europe and, significantly, received large financial backing:

There is a small question that the various Masonic lodges which he [Cagliostro] founded and which were patronised by persons of ample means provided him with extensive funds, and it is a known fact that he was subsidised by several extremely wealthy men, who, themselves dissatisfied with the state of affairs in Europe, did not hesitate to place their riches at his disposal for the purpose of undermining the tyrannic powers which then wielded sway.51

London was the centre of revolutionary intrigue, where political refugees from throughout Europe sought refuge and laid the foundations of the Internationale. Masonry provided acceptance for diverse and radical views, and a model for a secret revolutionary structure:

In any event, if your declared purpose was something as radical as that of the ‘Philalethes’, the perfection of the human race, it helped legitimize the goal by describing oneself as an ‘Ancient and Primitive Rite of Masonry’.52

In 1810, a revived Order of Memphis was established in France with 90 Degrees. It was recognised by the Grand Orient in 1826, and underwent a further revision in 1838 under Jacques Étienne Marconis, establishing lodges in Paris and Brussels and claiming adherents in England.

Lause, citing Spitzer and Hutton,53 states concerning the years following the French Revolution and the rise of the profane and Anti-Traditional societies:

Since the French Revolution, those eager to build political organization found freemasonry a ready model… An Italian participant in the French Revolution, Filippe Michele Buonarotti survived decades of repression, prison, and intense police scrutiny to launch a series of secret societies that remained viable well into the 1830s. Towards the close of this period, a student named Louis Auguste Blanqui entered this conspiratorial world, and remained influential within it as late as the 1870s. Blanqui’s Société des Saisons urged an ongoing revolutionary overthrow of the ruling classes until the process left the working class alone to exercise power.54

Some of the German émigrés in Paris, who founded the League of the Proscribed, adopted the doctrines of Blanqui. The League was brought to Germany under the influence of Johann Hoeckering, who had been a protégé of Buonarroti. From here the League of the Just, which became the Communist League, was formed. Engels described their goals as the same as those of the other secret societies in Paris at the time.

Among these secret societies was the Order of Memphis. The association was known to the authorities, who considered banning the Order along with the League of Just and the Blanquists. In 1839, the authorities decided not to ban the Order, but it declared itself dormant in 1841 to avoid any future possibility of that happening. The Order maintained its existence under its Paris organisation, the Loge des Philadelphes, which had a leadership that ranged from republicans to Blanquists. After the February 1848 Paris riots, Memphis resurfaced.

Lause identifies Louis Blanc, one of the primary leaders of the 1848 Paris uprising, as the ‘most prominent member’ of the Conseil Supreme de l’Ordre Maconnique de Memphis, and the Order became the major revolutionary faction of its own accord. Lause writes:

These radical masons rode the crest of radicalism into ‘the June Days,’ when the government force of 40,000 moved against an indeterminate number of workers, leaving between 4,000 and 5,000 dead with an unknown number of wounded. The state of siege continued in October, and the dictatorship that emerged banned the Order of Memphis, which moved its Supreme Council to London.

The repression against the revolutionaries led to their spreading further afield. Lodges were established in England and elsewhere, the most important being La Grand Loge des Philadelphes at London in 1851. The émigrés aligned themselves with radical English Masonic freethinkers engaged in agitation.55 This outgrowth led directly to the founding of the First International. Lause states:

Over the next fourteen or fifteen years, the order eased the alliance with revolutionaries of other nations. It fostered what became the International Association in March 1855. The Order of Memphis provided almost all of the French members of the General Council of the later International Workingmen’s Association.

Another prominent socialist historian, Dr. Bob James,56 draws similar conclusions to that of Lause regarding Freemasonry and the rise of socialism:

It’s neither accidental nor an aberration that reformers Garibaldi, Mazzini, Charles Bradlaugh and Karl Marx were all Freemasons, as were many ‘labour movement’ people in Australia.

James identifies the associations between the Internationale of Marx and Bakunin and the lodge of which Marx was an initiate:

What the author [Yorke] called the secret history of the [First Communist] International asserts:

‘The IWMA [Industrial Working Men's Association] in Geneva sought and found a temple worthy of their cult...a Masonic Temple...which they [Marx, etc.] rented. They put the name of ‘Temple’ on their cards and bills.

Bradlaugh acknowledges having been initiated into the Loge des Philadelphes, which is believed to have been Marx’s lodge, his ‘brothers’ including Blanc, Garibaldi and Mazzini. Founded in London in 1850, its initial members were émigrés from recognised foreign Orders, which perceived Freemasonry as:

An institution essentially philanthrophical, philosophical and progressive. It has for its objects the amelioration of mankind without any distinction of class, colour or opinion, either philosophical, political or religious; for its unchangeable motto: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.57

It is notable that Marx’s lodge, along with that of Blanqui and the others, was the ‘Loge des Philadelphes’, the parent lodge of the Order of Memphis, as identified by Lause, and from the records of the Internationale utilised by Nicolaevsky.

Anti-Europe

These revolutionary forces coalesced into the Young Europe movement founded by Mazzini in 1834, which in turn provided the foundations for what we might in this context term ‘Anti-Europe’, culminating today in what is called the European Union.

This Anti-Europe is not intended as a restoration of tradition, but as a phase in the formation of a Universal Republic, the ultimate goal being imprinted on the Great Seal of the United States as Novus Ordo Seclorum: ‘A New Order of the Ages’.58

This was also the aim of the French revolutionaries, and remains the aim of the Counter-Tradition. Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce, Baron de Cloot, who changed his Christian name to Anarchasis, declared to the French National Assembly on June 13, 1790 that the ‘Rights of Man’, the new law to replace the laws of God, must be adopted by all humanity, and that there must no longer be any sovereign nations. On 2 April, 1792 at the Convention he called for the creation of ‘La Republique Universelle’.59

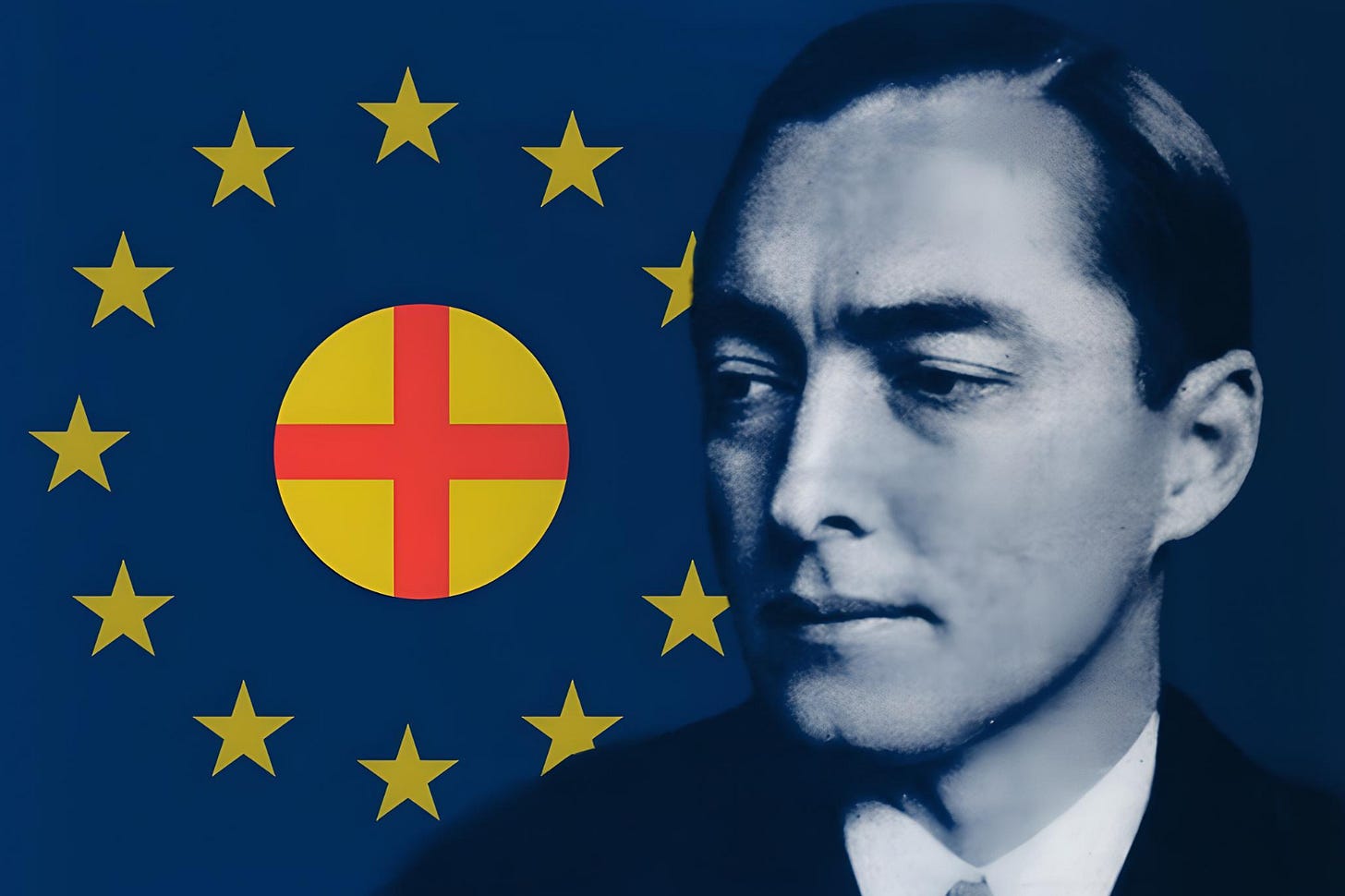

The modern movement took shape under Count Richard Coundenhove-Kalergi. The Masonic affiliation of Kalergi and the Masonic foundation of his Pan-European Movement are confirmed by the Assistant to the Grand Master of Romanian Masonry,60 Dr. Marian Mihaila, who states:

The adepts of the idea of a united Europe are grouped – as I have shown before - in the Pan-European Movement whose supporter was also a Mason, Count Richard N. C. Kalergi (the son of an Austro-Hungarian diplomat and of a Japanese woman). He was encouraged and financed by a series of American masons who wanted to create thus, according to the American model (the first Masonic state in history), the United States of Europe.61

With the interruption caused by the Second World War to the Masonic schemes, the movement was taken up again in 1946. Mihaila states of this time, ‘Being stopped during WWII, in August 1946 the Masons take up again their secular dream: they create the European Union of Federalists.’62 Note the reference to the ‘secular’ foundations for Europe, after the method of Anti-Tradition.

Also notable is that Kalergi was backed by Louis Rothschild and Max Warburg. Kalergi stated concerning this:

Early in 1924 Baron Louis Rothschild telephoned to say that a friend of his, Max Warburg, had read my book and wanted to meet me. To my great astonishment Warburg immediately offered a donation of 60,000 gold marks to see the movement through its first three years. Max Warburg was a staunch supporter of Pan-Europe all his life and we remained close friends until his death in 1946. His readiness to support it (the movement) at the outset contributed decisively to its subsequent success.63

Celebrating the 100th Jubilee of Kalergi, a 10-euro coin was minted in his honour in 1972, and a stamp printed in Austria.64

Dr. Corneliu Zeana, a high initiate of Romanian Masonry and the president of the Romanian branch of the European Movement, describes a federal Europe as being a manifestation of the ‘Masonic spirit’: ‘The blueprint of a new Europe was created on the basis of the great values promoted by Masonry …’65 Dr. Zeana concludes by stating that the contemporary moves for complete integration will continue under the watchful, all-seeing eye of Masonry:

In the actual period, the European Union needs a Constitution. The Laeken Convention (also called Convent, an adequate Masonic term for the reality of this reunion led by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, who needs no presentation for the illuminated and aware Masons) succeeded in editing it. Despite the difficulties, we are sure that the endorsement of the European Constitution is not far. The realization of a United Europe cannot be done at once. It needs the successive periods of an uprising evolution, far from perfection. We are the contemporaries, apprentices, fellowcrafts, masters and architects of this great edifice. We cannot pass through without pointing out the evolution of the terminology. From the European Economic Community (preceded by the European communities, ECCS and the EURATOM), the European Community to the European Union and maybe this is not it. These changes point to the fact that starting with the economic, there is a tendency to unite the politics, the spirit, the concept, the moral. And maybe the United Europe must represent, above everything, a moral space. Regarding this transformation, the vigilance of Freemasonry is a mission.66

This is not the Europe of Charlemagne. It is the Anti-Europe as a prelude to the Universal Republic, the Novus Ordo Seclorum.

33 Eliphas Levi, op. cit., Book 6, pp. 288-326.

34 Conrad Goeringer, ‘The Enlightenment, Freemasonry, and The Illuminati, Part I - The Enlightenment,’ at www.atheists.org/Atheism/roots/enlightenment/.

35 Abbe Augustin de Barruel, Memoire pur servir a l’histoire du jacobinisme, 1797.

36 John Robison, ibid. Like Levi, Robison was himself a Mason who was disturbed by the ‘profane’ subversion of the order, and specifically the actions of Continental Masonry.

37 Grand Orient of France: ‘History’, at //www.godf.org/foreign/uk/histoire_uk.html.

Note the open identification of the Grand Orient with revolutionists such as Blanqui and the anarchist Bakunin.

38 Eliphas Levi, op. cit., p. 310.

39 Eliphas Levi, ibid., p. 310.

40 A depiction of the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen’ can be seen at jspivey.wikispaces.com.

41 A depiction of the title page of the Encyclopedie can be found at library.usyd.edu.au.

42 John M. Roberts, The Mythology of the Secret Societies (London: Secker & Warburg, 1972), p. 230.

43 John M. Roberts, ibid., p. 266.

44 Nesta H. Webster, op. cit.

45 David Conway, A Farewell to Marx (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1987), p. 146.

46 Lause specialises in the history of the labour movement. An Associate Professor of History at the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Cincinnati, his faculty biography states that he ‘teaches specialized courses in American Labor History, Comparative Labor History, and the Age of Jackson… For years, he has presented his work or participated in panels at the Annual North American Labor History Conference at Detroit… and the centennial conferences on Eugene V. Debs and Henry George.’

47 M. A. Lause, ‘Walking Like an Egyptian: The American Destinies of a Revolutionary French Secret Society,’ available at www.geocities.com/CollegePark/Quad/6460/WalkingEgyptian4.html.

48 Eliphas Levi, op. cit., p. 301.

49 According to Lause, Boris Nicolaevsky based his work on the origins of the Internationale on the records of the organisation: ‘Clearly, when Nicolaevsky found the manuscript records on this society a century later, he opened a window into a genuine revolutionary conspiracy with far-reaching influences’.

50 Boris Nicolaevsky, Secret Societies in the First International: The Revolutionary Internationals, 1864-1943, ed. Milorad M. Drachkovitch (Stanford University Press for the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, 1966), p. 37.

51 Lewis Spence, An Encyclopaedia of Occultism (New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1960), ‘Cagliostro’, pp. 85-92.

52 M. A. Lause, op. cit.

53 Alan B. Spitzer, The Revolutionary Theories of Louis Auguste Blanqui (New York: Columbia University Press, 1957), pp. 4-5, 129-133; and Patrick Hutton, The Cult of the Revolutionary Tradition: The Blanquists in French Politics, 1864-1893 (Berkeley-Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981), p. 18.

54 M. A. Lause, op. cit.

55 I Nicolaevsky, op. cit., pp. 41-42

56 Dr Bob James is the Convenor and Co-ordinator of the Australian Centre for Fraternal Studies. He states of himself: ‘I make these claims on the basis of 25 years of research, of ten years or so as Secretary of the Hunter Labor History Society, and as organiser of a National Labor History Conference’.

57 James’ reference is O. Yorke, The Secret History of the International Working Men's Association (Geneva, 1871).

58 A lot of obfuscation takes place to try and refute claims that the Great Seal of the United States is a Masonic design. The fact remains however, that President Franklin Roosevelt, and his Vice President, Henry Wallace, both 32º Masons, recognised the Seal as Masonic, and Wallace arranged for the inclusion of the Great Seal on the American dollar bill, where it has remained. Wallace stated of the motto, ‘It will take a more definite recognition of the Grand Architect of the Universe before the apex stone [capstone of the pyramid] is finally fitted into place and this nation in the full strength of its power is in position to assume leadership among the nations in inaugurating “the New Order of the Ages.”’ Henry A Wallace, Statesmanship and Religion (New York: Round Table Press, 1934), pp. 78-79.

59 Quoted by Denis de Rougemont, The Idea of Europe (New York: Macmillan Co., 1966), p. 180.

60 Re-founded in 1989 under the auspices of the Grand Orient of Italy.

61 Dr. Marian Mihaila, ‘European Union and Freemasonry,’ in Masonic Forum, available at www.masonicforum.ro/en/nr27/european.html#b_22.

62 Dr. Marian Mihaila, ibid.

63 Richard Coundenhove-Kalergi, Pan Europe (Vienna: Pan Europa Verlag, 1923), pp. 59-66.

64 European Commission, Europäische Visionen: Der Vordenker Coudenhove-Kalergi, available at ec.europa.eu/news/around/080418_ger_de.htm.

65 Dr. Corneliu Zeana, ‘The European Union – a Masonic Accomplishment,’ at Masonic Forum, available at www.masonicforum.ro/en/nr20/zeana.html.

66 Cornelieu Zeana, ibid.

Pew... for a second there I was afraid you were gonna go into a whole other direction and claim something about an alleged "Kalergi Plan" to replace the "German Volk". Because that's actually antisemitic propaganda the Nazis came up with ever since Kalergi started criticizing Socialism AND National Socialism and Hitler AND Stalin. I have pretty much all of Kalergi's books, they are actually pretty good and there is no "Kalergi Plan" in them. Though what you are saying about him is of course different and that might very well be true.