‘Dead Souls’: 20 Years since Samuel P. Huntington’s Famous Essay

Laura Slot revisits the 2004 essay on the widening rift between American elites and the rest of the country’s citizenry. Twenty years later, it shows how globalization became ridden with betrayal.

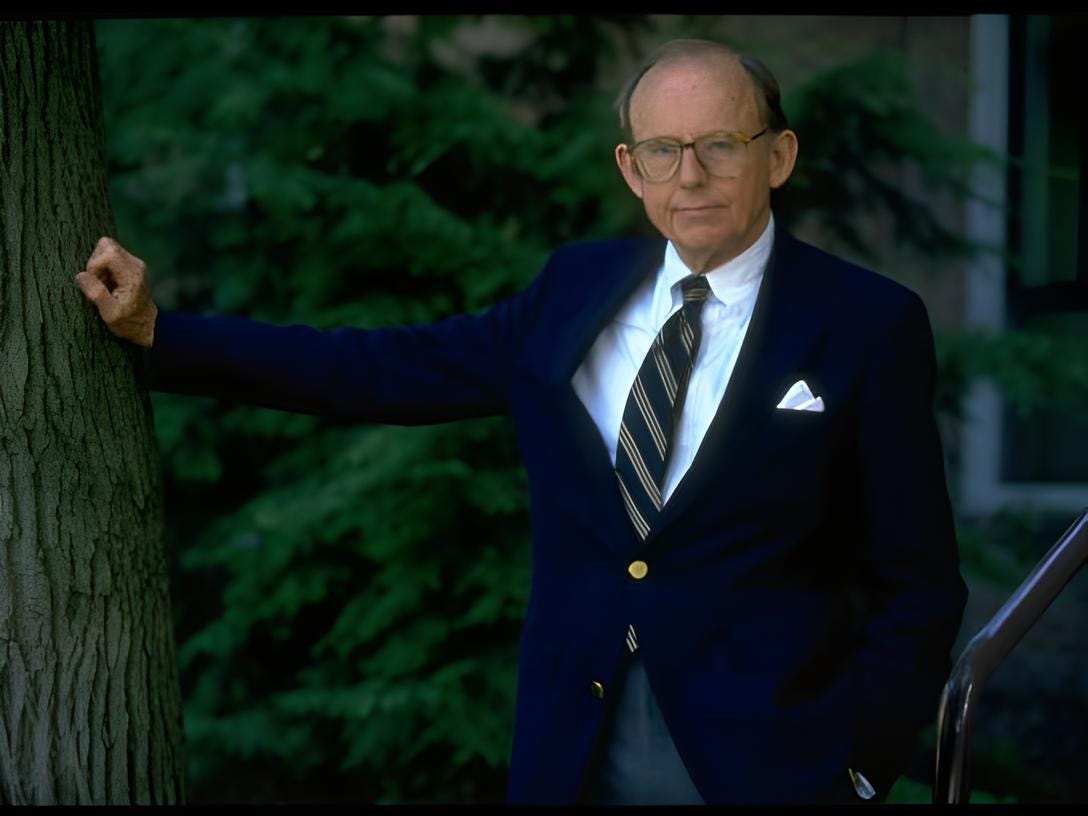

Harvard professor and political scientist Samuel P. Huntington (1927-2008) predicted many events correctly. His essay ‘Dead Souls: The Denationalization of the American Elite’ described how the US elites, which he marked at around 4% of the population, were divorcing themselves from America. The roots of this development he placed before 1980.

Huntington’s elites are dead souls — as he illustrates with Walter Scott’s poetry from 1804 — those who have forgotten where they came from. Those free-floating on opportunism while losing that what makes them human, who come and go without experiencing interconnectedness or the feeling of home. Who fill their existential voids with contempt for those who do still feel American, as well as those who attribute far less meaning to, as Huntington used Scott’s words, ‘titles, power and pelf’. Dead or dying versus living souls may be the only truthful form of partisanship.

‘Dead Souls’ is neither a prophetic warning nor a causal analysis. It is a scholarly, detailed observation of a geopolitical pattern. More historical and sociocultural descriptions had been made earlier, like Christopher Lasch’s The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (1996), and even earlier, Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind (1987) and Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (1984). Huntington steered clear of integrating these various angles and stuck solely to a political analysis.

One anecdote in the essay describes what many are beginning to observe today:

The rewards of an increasingly integrated global economy have brought forth a new global elite. Labeled ‘Davos Men’, ‘gold-collar workers’ or … ‘cosmocrats’, this emerging class is empowered by new notions of global connectedness. It includes academics, international civil servants and executives in global companies, as well as successful high-technology entrepreneurs.

Huntington estimated the size of this global elite at about 20 million in 2000, of which 40% were American, and he expected it to double in size by 2010.

In the rise of cosmopolitanism the main ideology is transnationalism. Huntington distinguished between economic, universal and moralistic transnationalism. The economic branch involves multinationals overpowering governments. The universal version is the idea that the whole world can culturally be considered Americanized. The moralistic branch believes that supranational morals are superior to national ideals and that national interests and patriotism are evil forces. The latter has seen much growth and Huntington was correct when he observed that it is mostly found among intellectuals, academics and journalists.

The foretelling essay shows the importance of releasing long-held thought patterns to make room for new ways of thinking, to learn to observe in a Huntingtonian fashion. Since its publication, commentators have often disregarded realpolitik — power structures and the pursuit of interests. This is now changing, because the spectrum of idealism has failed too often in explaining current affairs. Another major thought framework, that of American internationalism versus isolationism, has also proven outdated.

Whoever is capable of reading between the lines understands that ‘Dead Souls’ is appealing to a higher level of conscientiousness. Americans, Huntington wrote, are the proudest citizens in the world. No other nation shows such an immense devotion to and identification with nationality and country. This context makes the betrayal of the elite particularly painful. This is emphasized when he cites Abraham Lincoln speaking of ‘the mystic chords of memory’: the invisible bonds that run much deeper than words can describe. Huntington was right when he observed that the elite has forgotten this, but the people have not.

Commerce has no home. The commercial interest in America, which go back to Christopher Columbus, are brutal, ruthless, and placeless. The globalist, capitalist, communist, do not care about place or people of a place. They have no loyalty to any place. this is an ancient characterizationof the commercial system. Commerce is to be contrasted with barter and trade.

Good old Huntington, nice that someone refers to him in this day and age. However, Huntington never struck me as particularly innovative, clairvoyant, and intellectually challenging. Actually, he describes a phenomenon that is quite familiar to our Marxist colleagues: capitalists have no true fatherland and only identify with a particular nation if it suits their bank account. But then again, as a quintessential American, Huntington also liked re-inventing the wheel.