Conservative, Traditional, Eternal

by Dmitry Moiseev

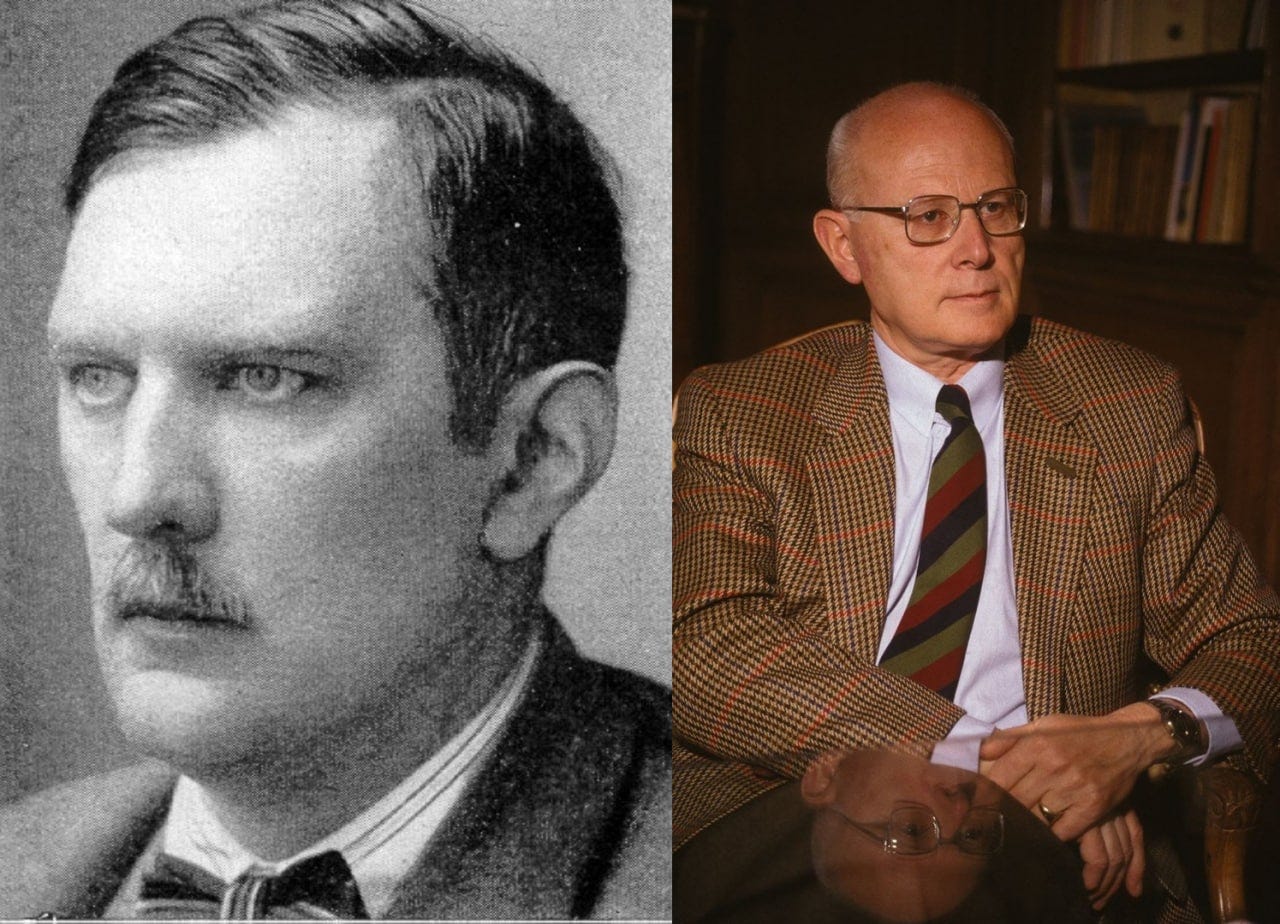

Dmitry Moiseev explores the enduring principles of conservatism and tradition through the insights of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Dominique Venner.

German thinker Arthur Moeller van den Bruck pointed out that “conservative is that which is justly realized again and again,” and the conservative idea is living and timeless. A conservative denies that the meaning of a person’s life is contained in the short time span in which he lives. He picks up what has been created by generations and passes his work on to his descendants. The transient does not interest him — his gaze is directed towards eternity. A conservative, living in connection with his own history, realizes what — as well as how and why — was built in his country. “All conservative demands: the protection of the nation, the preservation of the family, the recognition of the monarchy, the organization of life in discipline, the maintenance of authority, as well as the understanding of class, corporate, administrative hierarchy — all this is nothing more than the result of human insights,” writes Moeller. According to the German thinker, the key task of a conservative is “to preserve what can still be preserved.”

Moeller van den Bruck’s definition of conservatism resonates with the definition of tradition given by another twentieth-century thinker, Dominique Venner, in his work The Samurai of the West:

Tradition — as I understand it, in a new, even “revolutionary” way — is not a collection of customs and costumes, a certain way of acting or thinking, transmitted by education or practice. It does not oppose modernity any longer. Even less so, it is a collection of universal and mystical principles, imagined by Gnostics. It is not nostalgic memories of a vanished Golden Age. Tradition, as I understand it, is not the past; on the contrary, it is what does not pass and what eternally returns anew in different forms. It signifies the essence of civilization over a very long period of time, that which resists time and is preserved, despite the disturbing influences of borrowed religions, fashion, and ideologies.

From these two perspectives on essentially the same subject, one can conclude that only the eternal, which invariably “returns,” represents true value. The forms of the return of the eternal can change — they are dynamic in time and transient. The restoration of forms is absolutely meaningless. At the same time, the preservation or revival of fundamental principles that define the greatness of cultures, as well as their individual representatives, is necessary. The eternal is the last thing we can rely on at the present moment, “in the midnight hour of this world.”

(translated by Constantin von Hoffmeister)